Mountain trails crossing ice can be treasure troves of archaeological material. People lost or threw away all kinds of stuff on their way. If the objects were lost on the ice, they can still be preserved even though millennia has passed. You can find corpses, clothing, household items and dead pack animals. What more can you wish for as a glacial archaeologist? Of course, we like the hunting sites too, but there you know what you are going to find – arrows, bows, scaring sticks etc. This is not the case on the transport sites, where you can find just about anything.

We have one such transport site in Oppland – the trail over the Lendbreen ice patch, which was used from c. AD 300-1700. It has yielded hundreds of artefacts, e.g. Iron Age clothing, transport equipment and bones from packhorses. We suspect that there may be more such sites here. At the recent Frozen Pasts, the world conference on frozen archaeology, there were a number of interesting presentations on glaciated mountain trails by our colleagues in the Alps. Their work has inspired us to make an extra effort to locate more glacial trails here in Oppland.

There are two main ways of locating glaciated mountain trails, outside just going into the field and start surveying the vast landscape for clues. One is to check historical sources to find information on where mountain trails have crossed glaciers or ice patches. Some of these trails are still marked by cairns. However, this would only point to known trails, used in relatively recent times.

To look for other and perhaps older trails, one can analyze the topography of a mountain region using computer programs. This will help to find trails that afford the easiest way to travel to certain destinations from a specific starting point. This type of analysis, also known as least cost analysis, has been undertaken with success in the Alps. Unknown trails have appeared which have then been checked in the field, leading to archaeological discoveries. We have just started doing such analysis here.

The search for old ice trails in Oppland

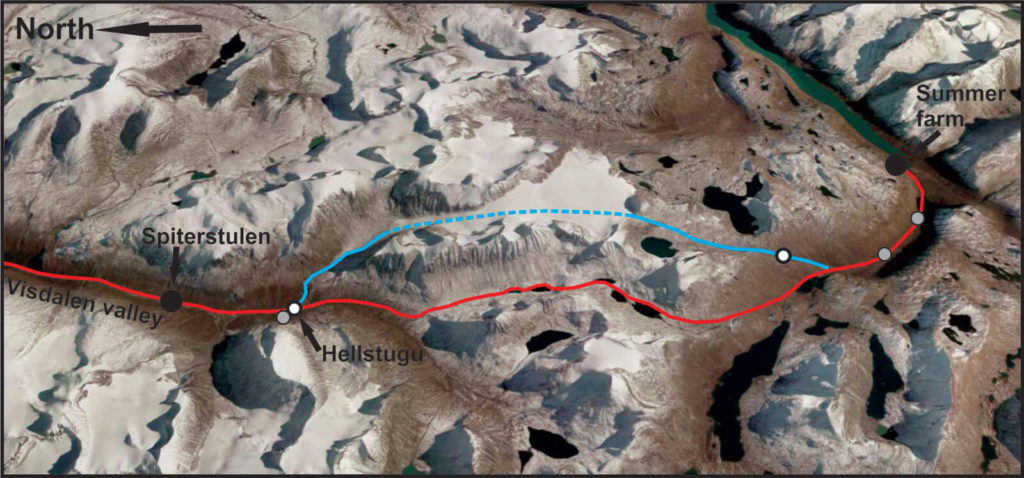

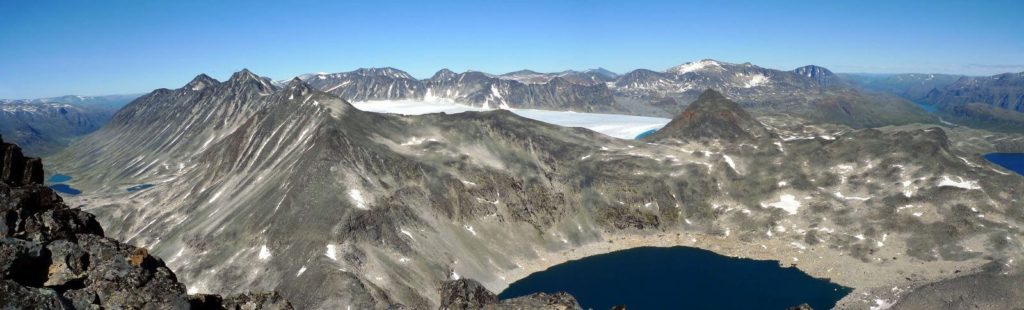

We have sifted the historical sources for information on ancient high mountain trails, and several ice-crossing trails have come up. The most promising ice trail appears to be the historical trail from the Bøverdalen valley to Lake Gjende over the connected glaciers of Hellstugubrean and Vestre Memurubrean. The highest point of the trail is c. 1950 m above sea-level. This trail also came up in the first preliminary least cost analysis.

The historical source

We are lucky to have an oral source describing the trip over the Hellstugubrean – Vestre Memurubrean glaciers. Gjendine Slålien (1871-1972) told her story in Arvid Møller’s biography of her.

“Already in May it was time to travel through the high mountains to Gjendebu, a long and somewhat dangerous trip on snow. First through the Bøverdalen valley to the Røisheim farm, and then then up the long and steep Visdalen valley. We spent the night in Hellstugu, where the river comes down from the Hellstugubreen glacier. The next day we continued over the Hellstugubreen glacier, via the Memurubreen glacier and on to the Memurutunga to the Storådalen valley. In the evening of day two, we would see Gjende.

And then back again in September. However, not before the first snow came to Gjende and hid the grazing areas beneath a thin layer of white. Then it was the same hard trip back.”

The same source also says:

“Dad started the trip home two days after we arrived at the summer farm. (…) He undertook the trip through the high mountains to Gjende every third or fourth week, but he was only there for two days before he loaded the packhorse and travelled back.

“It is nearly three hundred years since the farmers in the Bøverdalen valley realized that the mountain grazing at Lake Gjende was the best in all of the Jotunheimen Mountains”

There are a couple of interesting points here. Gjendine (as she is affectionately called locally) describes the use of the trail of the glaciers in the late 19th century, when she was a child.

She only says explicitly that they travelled over the glacier in May, not on the return trip, or on the father’s recurrent trips between the farm and the summer farm. There is another trail avoiding the glaciers, going through the Urdadalen valley. This trail is difficult to use in early summer due to heavy scree, often covered with rotten snow. The name of the valley literally translates as “Scree Valley”. It is likely that the choice of trail was opportunistic. Sometimes, especially during the winter, spring and early summer, the glaciers were snow-covered and easy to use. In the fall, the ice on the surface of the glaciers could have been exposed. This would have made them dangerous to cross with farm animals.

Gjendine states explicitly that they spent the night in Hellstugua, where the river comes down from the Hellstugubrean glacier. This is where the path up the Visdalen valley splits in two – one going up the valley to the glacier and one going through the Urdadalen valley. There is a known house ruin here, presumably the Hellstugu itself, which gave name to the site and the glacier. It has not been investigated yet and the date is unknown. Elsewhere in the mountains of Oppland, this type of mountain cabin, built for the protection of mountain travelers, are dated to the early Medieval Period (c. AD 1100).

Gjendine does not say that they arrived at the summer farm in the evening of day two, only that they could see the lake. We have information that there is a house ruin on the south side here. The could be the remains of a cabin with a similar function as the Hellstugu cabin. So far, it has not been visited by archaeologists.

How old is the trail across the ice?

From Gjendine’s testimony, we have solid evidence that the trail over the glacier was used in the late 19th century. At that time there appears to have been a local tradition that summer farming at Lake Gjende started almost three centuries earlier. Presumably, this could push back the use of the trail to this time. There is no good evidence of earlier summer farming in the historical sources. The earliest source is from 1767, where farmers from Bøverdalen valley and Lom state that they had used the areas at Lake Gjende from “old times”. There are house ruins in two separate places in the Storådalen valley leading up from Gjendebu on the way to the glacier crossing. In 1888, it was said that they were the remains of summer farms belonging to the Glømsdal and Hoft farms. Both these farms are situated in the Bøverdalen valley.

Based on grave-finds, the Bøverdalen valley to the north of the crossing was settled in the Viking Age at the latest. Pollen analysis at the Spiterstulen summer farm in Visdalen (now a popular tourist lodge) has indicated that both grazing and growing of barley took place here from AD 750-1350 and again from 1650 onwards. This is in accordance with the current theories on the establishment of the summer farm system in the Viking Age, a collapse after the Black Death and the establishment of the historical summer farm system in the 17th century. However, there are also indications of grazing in the late Bronze Age at Spiterstulen, as there are elsewhere in this mountain region.

There are remains of building foundations higher up in the Visdalen valley, quite near the ruins of the Hellstugu. The location is called “Gamalsetre”, i.e. old summer farm. The house foundations have not been investigated archaeologically yet.

There are also reports of stone-built cabins in the Memurudalen valley. This valley can be accessed from the Vestre Memurubrean glacier. These cabin remains are not dated, and their exact location is not known.

The finds from the Lendbreen ice patch, which was crossed by a mountain trail, gives solid information on the age of the traffic in the high mountains in the region. The traffic over Lendbreen appears to have started or at least increased significantly from around AD 200-300 onwards. The transport may not just be local, such as going to and from the summer farms. Long distance transport is also a possibility.

How will the glaciers influence what we can find?

Before starting the fieldwork, there remains a fundamental question. How will the moving ice in the glaciers have affected the finds? There are several different issues to consider here.

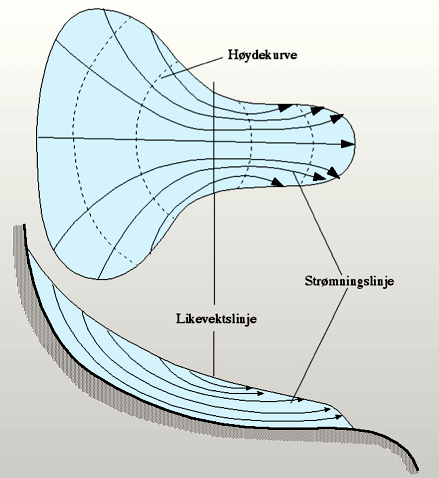

In general, the ice in the upper part of the glaciers, above the so-called equilibrium line, moves downwards from the sides towards the middle. At the same time, the surface ice sinks into the glacier. In the lower part of the glacier, below the equilibrium line, the opposite happens. This means that the finds will eventually end up on the surface of the lower part of the glacier, independently of where they were lost. If they were lost above the equilibrium line, they will only appear on the surface close to the end of the glacier. If they were lost on the surface below the equilibrium line, they will not disappear into the ice. That is, if they are not lost in a crevasse.

We know from the studies of old mountain trails in the Alps, that the glacier ice moves the finds downslope and scatters them, but that it does not necessarily crush them.

The glaciologists at the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate have conducted measurements on the glaciers in question. They move between 5 and 15 meters pr. year. Both Hellstugubrean and Vestre Memurubrean are a little more than 3 km long today. If we use 10 m as an average ice movement per year, this would imply that ice older than 3-400 years is no longer preserved in the glaciers. Artefacts older than this would have been dumped in front of the ice.

The Little Ice Age (LIA) glacier front from c. AD 1750 is a further 1.3 km down the valley from the current position of the Hellstugubrean glacier front. Material that was deposited here in 1750 would have been anywhere between 0-500 years old. There is some uncertainty about this, as the larger ice-mass may have sped up the ice movement, potentially changing the scenario somewhat. The LIA glacier front is as low as 1400 m, and the material dumped here would have been out of the ice for more 250 years. Therefore, only metal objects have a real chance of surviving here until present.

Material earlier than ca. AD 1200-1300 would have been deposited at the glacier front further up the valley and then covered by the advancing glacier during the LIA. This should only leave marginal chances of recovering Pre-Medieval material, and again only in metal. This implies that we can probably best investigate the earliest use of the trail by investigating ancient monuments connected to the trail, such as the Hellstugu house ruin.

Chances are better for recovering material from the Post-Medieval Period, and especially after the LIA, as the ice would generally have been retreating during the time of deposition in front of the glacier. However, there have been a number of smaller glacier advances since the LIA maximum, which could have buried material beyond reach. For organic material to be preserved, this material would likely have to be recovered from just in front of the glacier or on the glacier itself.

First fieldwork

The coming blogpost will be about the first fieldwork we have just undertaken on the northern part of the trail. We have inspected the Hellstugu house ruin and the nearby Gamalsetre ruins and surveyed for old trails. We also paid a rather sobering visit to the front of the Hellstugubrean glacier.