One of the great things about archaeology is when you get to survey a new area with little prior information. What discoveries are waiting out there? This time we headed out to do an initial survey of a historical trail crossing two glaciers in the heart of the Jotunheimen Mountains. The trail has not been surveyed by archaeologists before. For background information on the glacier trail read here.

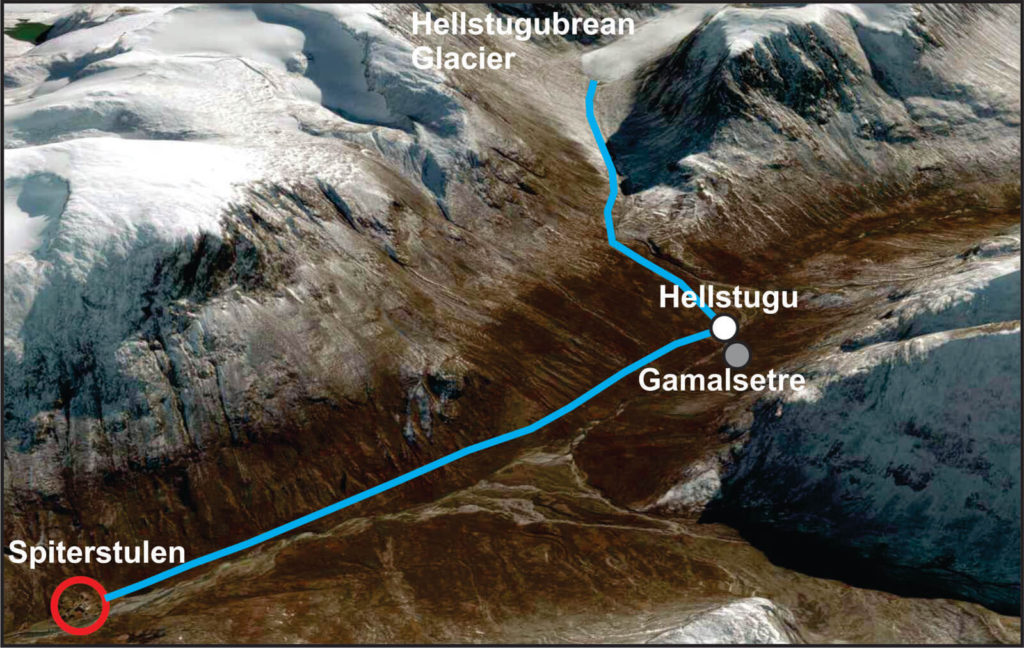

The plan for the first fieldwork was to survey the northern part of the glacier trail. We planned to look for old, overgrown trails away from the tourist trail. First stop would be the Hellstugu house ruin, where we were expecting to camp for the night, after documenting the ruin. The plan for the next day was to visit the Hellstugubrean Glacier to get an impression of the chances of discovering archaeological finds here. We also planned to pay a visit to the Gamalsetre ruins, just below Hellstugu (see map).

Getting to Visdalen and Hellstugu

The drive from Lillehammer to the Spiterstulen Mountain lodge lasted about three hours. The last part of the ride took us from the Bøverdalen Valley up through the lower and steeper part of the Visdalen Valley. This was roughly the same route taken by Gjendine Slålien and her family in the late 19th century, on their way to their summer farm at Lake Gjende, using the glacier trail.

After arriving at Spiterstulen, we checked our packs and equipment and headed out. By this time, it was late afternoon. There is a much-used modern tourist trail going up through the Visdalen Valley from Spiterstulen. We avoided this trail, and surveyed the terrain a bit further up the hillside. We found a number of overgrown trails and some collapsed cairns. Are these trails and cairns related to the old traffic through the valley? It seems likely.

As we got further up the valley, we were caught in heavy rain and sleet. We had to make a dash for the Hellstugu ruin site. When we got there, we were excited to see how it looked. However, with the rain pouring down, we just had to get the tents up, and get inside. The planned investigation of the house ruin would have to wait until the next morning.

The Hellstugu house ruin

Early the next morning the weather had cleared. It was cold and there was new snow on the mountains. Good conditions for surveying. After breakfast and some hot coffee, we went back to the Hellstugu house ruin, which was just 50 m from our night camp.

The house ruin is rectangular in shape, roughly 5×5 m. The walls are marked by low stone courses. A wooden building would have stood on this stone foundation. Without an excavation it is too speculative to suggest how the building would have looked. The most intriguing part of the ruin is a small separate room in the southwest corner, which we will get to shortly.

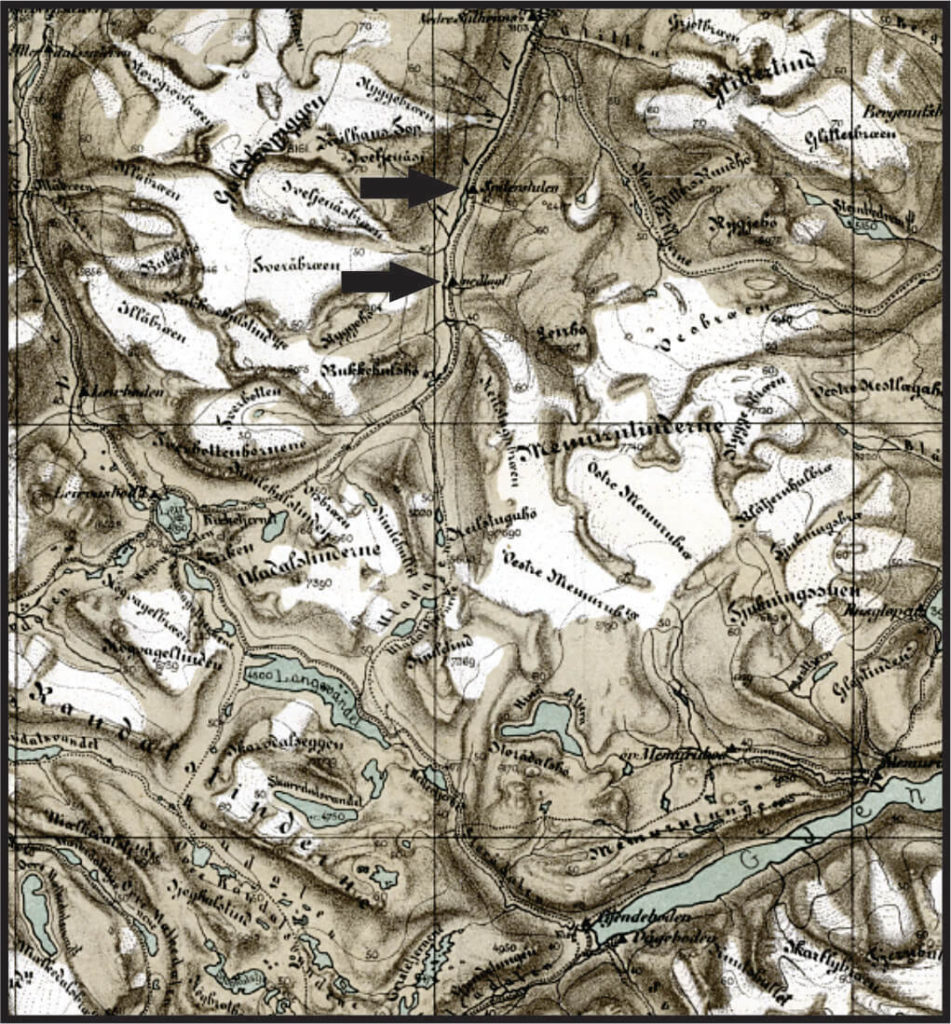

However, the first question (as always) is the age of the ruin. The stone courses are well visible, and this could suggest a post-medieval date. On the other hand, similar-looking ruins in nearby mountains have been excavated and radiocarbon-dated to the Medieval Period. Adding to the uncertainty is the statement by Gjendine Slålien, that they slept “i Hellstugua” (in Hellstugu), before crossing the glacier the next morning. This could potentially bring the date of the building up to the late 19th century. However, an 1879 map, contemporary with her stay, shows no cabin here, while nearby Gamalsetre is marked as “nedlagt” (abandoned). Spiterstulen, the Gjende summer farm and other mountain cabins are also marked. Presumably, this suggests that there was no standing building here in 1879. Perhaps Gjendine and her family slept inside the ruin. Alternatively, is she referring to the general area by the name of the ruin?

The original function of the building could help us date it. Based on a royal decree, cabins of this type were built in the Early Medieval Period to provide shelter for mountain travelers. Just how life-saving these cabins could be, is best understood by the detail by which the medieval law text describes their use. The words of the law carefully outline who gets to stay for and how long. It also states that if there are travelers, who should have left the cabin and refuse, and this leads to other travelers dying outside, then the ones refusing to leave have to pay a hefty fine.

A local medieval document describes the obligation of farmers to bring down the dead from the mountains. The Hellstugu house site also hints at the mountain dead, in the shape of a small room in the southwest corner. Tradition has it that such rooms were used to store the corpses of dead travelers, before they could be brought down and interred in the nearest cemetery.

After inspecting the Hellstugu ruin carefully, we believe that it is probably of medieval origin. The location at the exact spot where the path splits in two, with one trail leading up to the glacier crossing, adds a much deeper time depth to the use of the glacier trail.

The Front of the Hellstugubrean Glacier

The next part of our fieldwork was following the trail from the Hellstugu ruin up to the Hellstugubrean glacier. Again, we avoided the much-used tourist trail along the river, and surveyed higher up. Just as was the case leading out from Spiterstulen, there were clear marks of overgrown trails and collapsed cairns in the slopes, telling a story of older traffic here.

The main reason for visiting the glacier was to get an impression of the chances of discovering archaeological finds. There are big differences between glaciers and ice patches, when it comes to archaeology. The main difference is that the ice in glaciers moves, while the ice in ice patches either does not move or only moves very slowly (read about glaciers and ice patches here). In addition, not only does the glacier ice move, displacing and crushing the artefacts, but it also reshapes the landscape in front of the ice, through glacial advances, debris and meltwater. Of course, we knew this prior to the visit at the Hellstugubrean glacier. Nevertheless, one thing is knowing it on a theoretical level, another is experiencing it close hand.

As we left the grassy slopes and entered the stone-covered area within the Little Ice Age maximum extent, it quickly became clear that the chances of making archaeological discoveries here were minimal. Only metal objects would have survived the long exposure after the ice melted away. In addition, the objects would most likely be buried beyond our reach by glacial debris and meltwater sediments. We would have to survey on the ice.

After reaching the glacier front and a quick lunch, we walked on to the glacier and started surveying. The debris-filled glacial ice was exposed here and the small crevasses were clearly visible. This made it safe to survey without ropes, crampons and other safety measures, which should otherwise always be used when walking on glaciers.

No finds were made, and the reality is that we would have had to be extremely lucky to make an archaeological find on the surface of the glacier. There is just so much ice and so few artefacts. We would have had to be there at just the right moment when the object melted out, and before meltwater washed it down into the sediments in front of the glacier. Nevertheless, you have to be an optimist to be a field archaeologist. Otherwise, you are in the wrong profession! It was a long shot, but we tried.

It is no coincidence that many of the finds from glacial ice in the Alps have been made by mountain tourists. There are just many more tourists than archaeologists walking on the ice. In addition, tourists pass potential find spots every day in the hiking season, not just on a certain date during a scheduled survey. Maybe we will see tourists making finds on the Hellstugubrean glacier in the future. You have to be an optimist…

The Gamalsetre ruins

On the way back to the Spiterstulen lodge, we crossed the river for a short visit to the ruins at Gamalsetre. The name means “Old summer farm”, which is a sort of give-a-way for the original function of this site. As mentioned above, the site is marked as abandoned on an 1879 map.

There are at least five or six large house ruins here. The landscape is also clearly influenced by former grazing, as can be seen by the fertile vegetation. This is a clear contrast to the area around the Hellstugu ruin, which just has the usual mountain vegetation.

Local tradition has it that this summer farm at 1200 m above sea level was abandoned during the Little Ice Age as climatic conditions deteriorated. The summer farm is supposed to have been moved down the valley to the current site of the Spiterstulen lodge. However, pollen analysis at Spiterstulen shows agriculture here already from AD 750-1350 and again from AD 1650 onwards. This suggests that summer farming was already taking place at Spiterstulen when Gamalsetre was abandoned. Therefore, the traditional story does not quite fit the evidence.

The number of ruins and the clear cultural vegetation imprint in the surrounding landscape tells a story of a summer farm, which must have existed for some time. It appears less likely that this was just a Post-Medieval summer farm, which was quickly abandoned during the Little Ice Age. More likely, there was a summer farm already during the Medieval Period, but if so – what is the connection between the summer farm and Hellstugu traveler cabin?

What did we learn from the first fieldwork?

The fieldwork on the northern part of the glacier trail gave some answers, but it certainly also raised new questions.

The Hellstugu ruin is well preserved. It is rectangular, with a small room in one corner, maybe for the corpses of unlucky travelers, just as is known from the Alps. Similar houses elsewhere in Oppland are medieval. The system of mountain cabins for travelers is also rooted in the Medieval Period, and are described in the laws of the period. But for how long was the mountain cabin used?

The number and size of the ruins at the Gamalsetre location is intriguing. Is this really just an abandoned summer farm? How old is it, and what is the relation to Hellstugu?

The visit to the Hellstugubrean glacier confirmed that surveying for artefacts on or in front of the glacier is challenging. Chances of finding artefacts on scheduled archaeological fieldwork are very small. We will probably have to rely on lucky finds reported by tourists, if there are any artefacts still preserved here.

One way to get more information on the age of the glacier trail would be to excavate one of more of the preserved house ruins, especially Hellstugu. We can also use metal detectors to check the trails leading up to the glacier for datable artefacts such as horseshoes. A brief note of caution, in case someone should feel tempted to “help”: You need a permit from the park authorities to use a metal-detector in the national park. All the ruins mentioned in this text are protected by law.

The next fieldwork on the glacier trail will be on the southern side, from the summer farm at Lake Gjende up to the where the trail leads on to the Vestre Memurubrean glacier. There are several reported house sites on this trail. This fieldwork will most likely take place in early September.

If you have information concerning the glacier trail, we would very much like to hear from you.