Secrets of the Ice

The Archaeology of Glaciers and Ice Patches

Jan 14

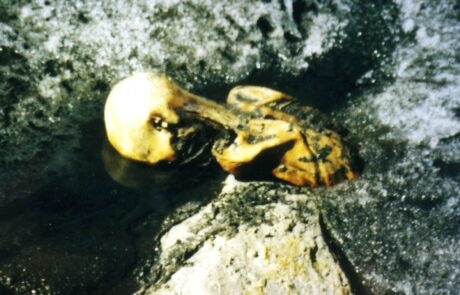

This arrow is incredible — the quartzite arrowhead is still in place, held by black pitch and fibres. At first glance, it may look like the stone was hollowed out for the shaft, but it is the black pitch you are seeing. The arrowhead itself is barely visible along the edges of the pitch.

The wooden shaft survives in three pieces, and the fletching is preserved — probably three feathers 😮 It dates to the Late Stone Age or Bronze Age.

Without the ice, only the stone arrowhead would have survived. Pitch, fibres, wood, and feathers — the details that show how it was made — would have been lost.

This week, we’re sharing five ice finds that would not have survived without the ice.

#glacialarchaeology #climatechange #globalwarming #climatechangeisreal ...

Jan 13

This is one of our most remarkable arrows from the ice 🏹

It has an arrowhead made from freshwater pearl mussel shell — and it is around 3,600 years old, from the Early Bronze Age.

Shell arrowheads were completely unknown in European archaeology until they started melting out of ice patches in southern and central Norway. We have now found three, with a few more known from neighbouring areas. Outside Norway, similar arrowheads are only known from the northwest coast of North America.

We found this arrow just after it melted out of an ice patch in the Jotunheimen Mountains — preserved thanks to centuries in the ice.

This week, we are sharing five ice finds that would not have survived without the ice.

#glacialarchaeology #globalwarming #climatechange #climatechangeisreal ...

Ice patches are not just natural freezers — they are fragile archives of past human activity. The objects they preserve, from arrows and shoes to tools and textiles, tell us stories that would otherwise be lost.

The photo shows an Iron Age arrow with its front still embedded in the ice, while the back end, including the fletching, has melted out. This striking image illustrates how ice can preserve even delicate details for centuries until melt exposes them. This arrow is so well preserved that it has probably been out of the ice no more than once since it was lost during reindeer hunting 1,500 years ago. At that time, it was flushed by meltwater to the front of the ice and quickly re-covered by ice.

These ice archives are highly sensitive to environmental change. Even small increases in temperature accelerate melting, and once objects leave the ice, they are exposed to the elements and degrade quickly. Human-caused climate change is speeding up these processes.

Every artefact recovered gives us a snapshot of the past, but it also reminds us that these windows into human history are shrinking. By studying the objects and the ice that preserved them, we can learn not only about ancient human activity, but also about how mountain environments are responding to rapid environmental change.

This week, we have shared a series explaining how artefacts are lost into the ice, how they are preserved, and what happens to them once they melt out — and what role global warming plays in their exposure. Thank you for following along! ...

After artefacts are washed down the ice surface by meltwater and end up on the ground in front of ice patches, their story isn’t over. Ice patches are very sensitive to changes in weather and climate and can advance or retreat from year to year, meaning objects may be exposed, covered, and exposed again.

The photo shows Iron Age scaring sticks lying in front of a small ice patch in Jotunheimen, with a team member pointing to them. These fragile wooden objects have survived for centuries in the ice, but each period of exposure subjects them to the elements, causing cracks, rot, and other damage.

While exposure and reburial have always happened naturally, recent warming is increasing the speed and extent of melting, putting artefacts at greater risk of damage once they leave the ice.

This week, we are doing a series that explains how artefacts are lost into the ice, how they are preserved, and what happens to them once they melt out. This is the fourth of five posts. ...