How can archaeological finds survive inside or beneath massive glaciers? Well, they can’t! The constant movement of the ice crushes the artefacts and eventually dumps the sad remains at the mouth of the glacier. When you hear about exciting discoveries from glaciers, these finds tend to be relatively recent, like missing airplanes or WW1 soldiers.

Luckily for glacial archaeologists not all ice in the high mountains moves. We would have made much fewer finds if it did! Non-moving fields of ice may be attached to glaciers, and are good places to look for artefacts. Ice patches, isolated non-moving accumulations of ice, also exist. They are excellent contexts for the preservation of artefacts, once lost in the snow.

Glacier or ice patch?

The basic difference between a glacier and an ice patch is that a glacier moves, while an ice patch does not move much (but read below). Ice masses can switch between being ice patches and glaciers over time. During a colder climate, like “the Little Ice Age” (AD 1450-1850), ice patches increased in size. Some of them reached a point where they became sufficiently thick (25-30 m) to start moving and turn into glaciers. Virtually all glaciers have started as ice patches.

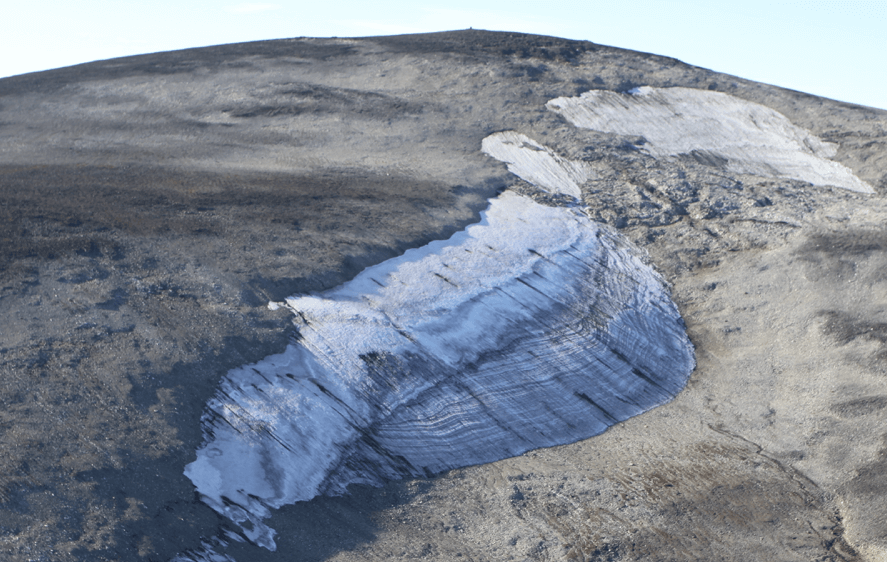

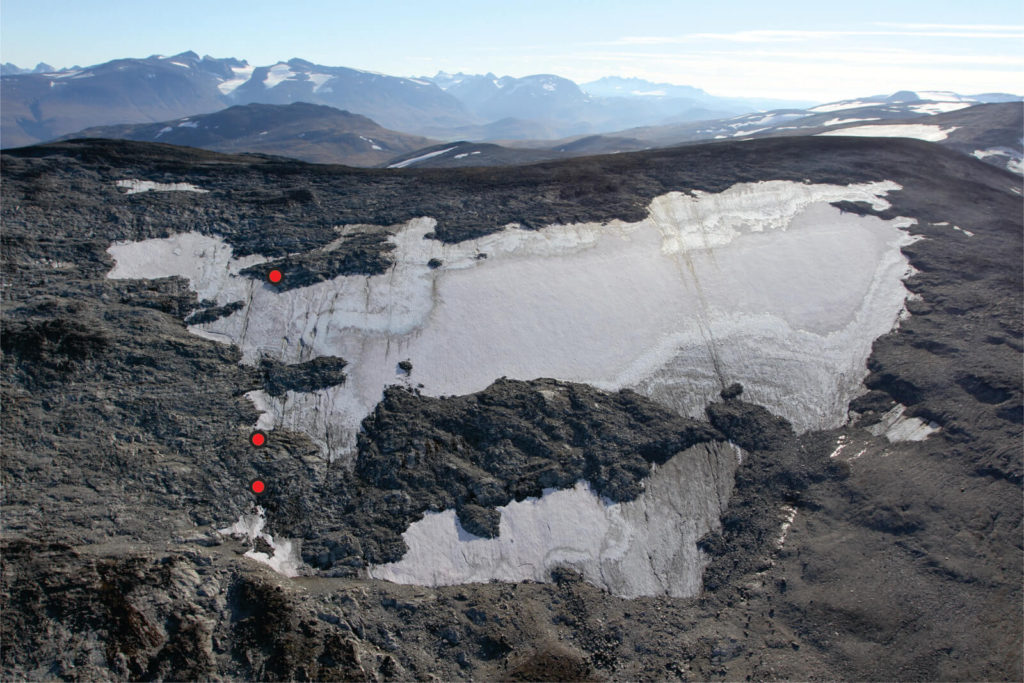

The ice in the larger ice patches can deform due to the pressure from the overlying ice. This process is very slow compared to the fast movements of glaciers. The lower ice layers compress and stretch, which can lead to very finely laminated ice. If the topography below the ice patch is flat, as in the photo above, the lamination will be quite even. On the other hand, if the topography is uneven, the stratigraphy will be more undulating, sometimes leading to strange and beautiful layering in the ice (see photo below).

Ice patches as archaeological sites

Even when ice is not moving or deforming only very slowly, it provides special challenges for archaeologists as a find spot. Ice patches react quickly to changes in climate, mainly winter precipitation, summer temperature and wind. Even if objects were originally lost in the snow, most of them melted out of the ice after that. Then snow and ice recovered them. This is the reason why we find most artefacts on the ground and not on the surface of the ice. We only find objects on the ice, when the melting reaches ice layers previously untouched by melting.

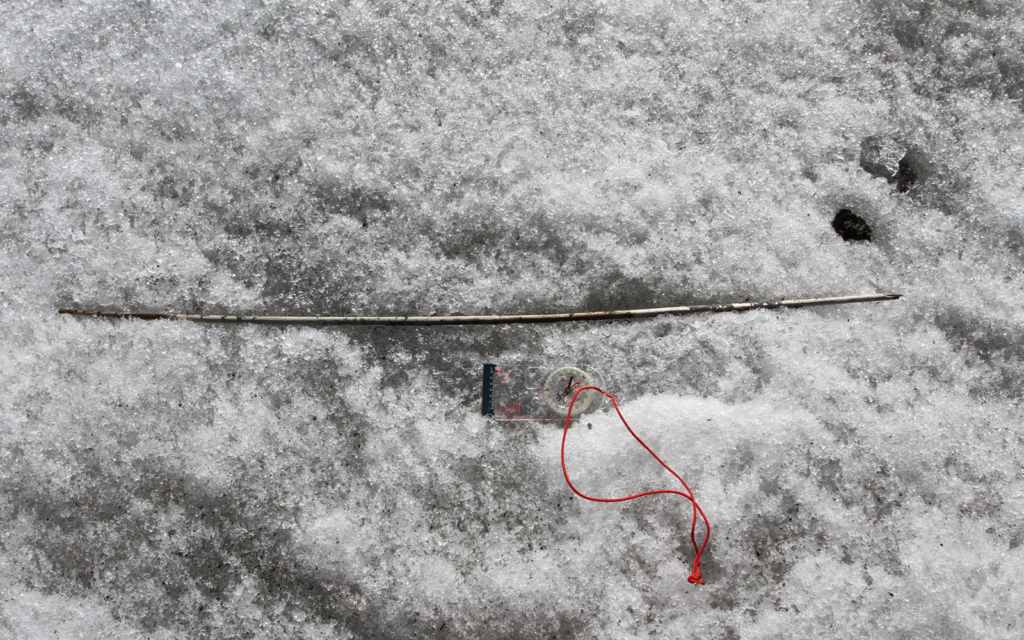

Artefacts only melt out of their original ice matrix when old ice melts. Such finds are therefore quite rare. Meltwater and wind move the objects. Parts of the same object can be found several hundred meters apart. The distribution of finds on the sites is thus difficult to interpret. We need to know if the artefacts lie where they were originally lost or if are they displaced?

Preservation of artefacts

Length of exposure plays a major role in the preservation of artefacts found at an ice patch. This factor often correlates with the distance of the find spot from present day ice – the further away from the ice, the poorer the preservation. This may appear self-evident, but sometimes local conditions around the find spot may also be beneficial to artefact survival. This could, for example, be a large boulder that collects extra snow, and provides shade.

Different types of artefacts also preserve differently, depending on their material. Arrowheads made of stone or metal preserve well but are hard to spot among the stones, if there is not an associated arrow shaft. Wood, birch bark and bone preserve best of the organic materials, while sinew, hide and textile deteriorate more rapidly.

The landscape surrounding ice patches also varies a lot. Some ice patches lie in a landscape with active processes, for instance steep slopes where rocks move. Others are in flatter areas with active permafrost. Such active geomorphological processes offer poor preservation conditions for artefacts.

From the above, you can see that there are a lot of natural processes going on at glacial archaeological sites. These processes transform the archaeological record, sometimes beyond recognition. We have published a first scientific paper on these processes. We need a lot more research though – glacial archaeology is a young branch of archaeology, and there is still a lot we do not understand. However, we can say for certain that glacial archaeological sites are a very different story than traditional archaeological sites in the lowlands.