We expanded our glacial archaeological fieldwork in 2010, thanks to government funding. For the first time, we had a team in the field that targeted multiple sites during the field season. However, the funding did not permit large-scale systematic surveys like that conducted at Juvfonne the previous year.

Nevertheless, we carried out exploratory surveys of several sites. In addition to recovering many artefacts, these surveys provided valuable information on both the number of finds and the logistics required for conducting surveys there. Altogether, we targeted nine sites, and, furthermore, our long-time collaborator Per Dagsgard reported a find from a new ice patch. To keep the focus clear, we will concentrate on our primary fieldwork in this post, highlighting the main sites and finds of the year.

There was little snow during the winter of 2009/2010, and by the start of the field season in mid-August, conditions for surveys were favourable. However, weather in the high mountains is unpredictable, and two snowfalls in late August caused a prolonged halt in fieldwork. Additionally, winter snow arrived early, which made the field season feel rather truncated.

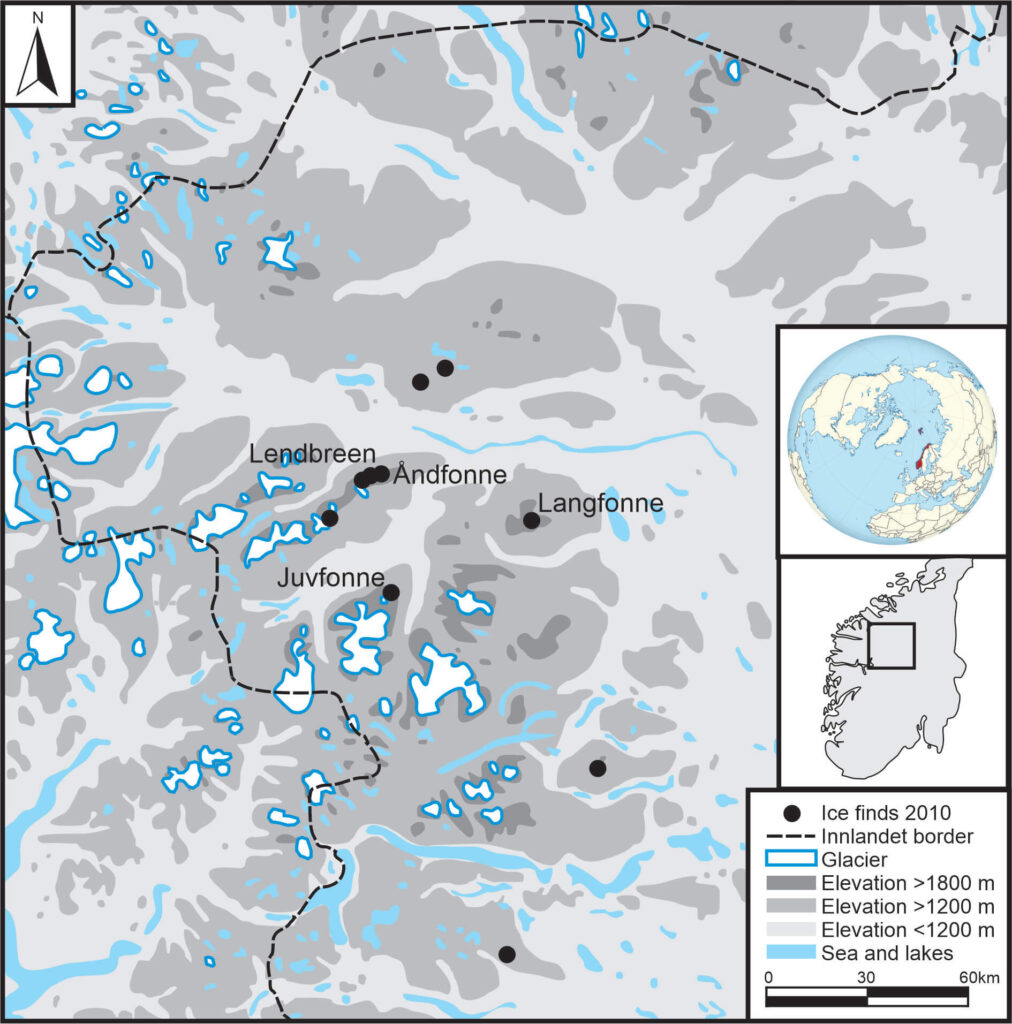

Fieldwork in the Lomseggen Mountain Range

In 2010, we targeted sites in the Lomseggen mountain range on three occasions. The national Norwegian television broadcaster, NRK, expressed interest in joining us in the field to produce a short documentary. They accompanied us on our first fieldwork trip on August 9 and 10, during which we conducted limited surveys at the Lendbreen and Åndfonne sites.

Lendbreen

Snow still covered the higher parts of Lendbreen. During our first visit, we crossed a large snow-filled depression at the summit without noticing anything unusual. It was only the following year, in 2011, when all the snow in the depression melted away during a warm summer, that we discovered what was hidden beneath.

We documented a line of scaring sticks and wooden posts positioned between the lower edge of the Lendbreen ice and the lake. It appeared to have been used to guide reindeer into the lake, where they would have been easy targets for hunters. Radiocarbon dating of a sample from one of the scaring sticks indicated a date of AD 345–410.

Åndfonne

However, it was at neighbouring Åndfonne that we made the discovery of the year: a large cache of scaring sticks, left among the stones approximately 1,500 years ago during the Iron Age. When we first visited the site, the cache was still partly encased in ice. We decided to leave it in place to allow natural melting to expose it fully. Ten days later, we returned to find the cache completely uncovered, enabling us to recover it in its entirety.

We also discovered three Iron Age arrows at Åndfonne in 2010. During our survey around the entire ice patch, we gained an understanding of where the finds were concentrated. Additionally, a local mountain hiker discovered a fragment of a hide shoe at Åndfonne, which we radiocarbon-dated to AD 430-540.

Fieldwork at Langfonne

The field team visited Langfonne on August 23, where they promptly discovered two arrows—one dating to the Iron Age and the other to the early Medieval Period. They camped high on the site but awoke on the morning of August 24 to find themselves in a snow-covered landscape. As a result, the survey had to be discontinued, and they returned to the lowlands.

Fieldwork at Juvfonne

Later that week, more snow fell, and conditions became challenging. It was not until we returned to Juvfonne on September 9 and 10 that more sustained fieldwork could be resumed. We surveyed the newly exposed terrain along the edge of the ice and collected an additional 58 scaring sticks. A journalist from Reuters visited our fieldwork at Juvfonne, marking the first time that international media showed interest in our work. This experience opened our eyes to the broader significance of our research beyond our immediate circle. You can find the Reuters article here. The Guardian also published a story on our finds.

The Ice Tunnel

2010 also saw the opening of the Climate Park at Juvfonne. Work on the ice tunnel began in May. Initially, we were assisted by a group of French mountain guides with experience in cutting tunnels through glaciers. They used a specialised ice pick to chip away at the ice. Despite the hard work, the process was remarkably efficient. In June, Norwegian ice artist Peder Istad shaped the interior of the tunnel, sculpturing the ice and illuminating it with LED lights.

The ice tunnel opened to the public on June 22 and quickly became popular. Erik Solheim, the Minister for the Environment, along with other key decision-makers, visited the ice tunnel in August. They saw the ice melt and the archaeological finds firsthand. The visit marked a decisive step towards securing permanent funding for a glacier archaeology program in Innlandet.

Summing up 2010

2010 became a year of intensive fieldwork after we received our first substantial government funding. We targeted nine sites, some of which we visited repeatedly. A 1,500-year-old cache of scaring sticks at Åndfonne was the most significant discovery of the year. The Climate Park and the ice tunnel at Juvfonne opened to the public in June. Reuters published the first international news story about our work. All in all, an effort we could be happy with. What would 2011 bring?

Posts for other years of fieldwork can be found here.