The 2015 fieldwork season in glacial archaeology proved unusually challenging. The winter of 2014/2015 brought heavy snowfall, and summer of 2015 stayed unusually cool. By mid-August, when we were due to begin fieldwork, the old, dark ice was still buried beneath fresh snow. We chose to postpone the start in the hope that conditions would improve. At the same time, we scaled back the team from six participants to just four.

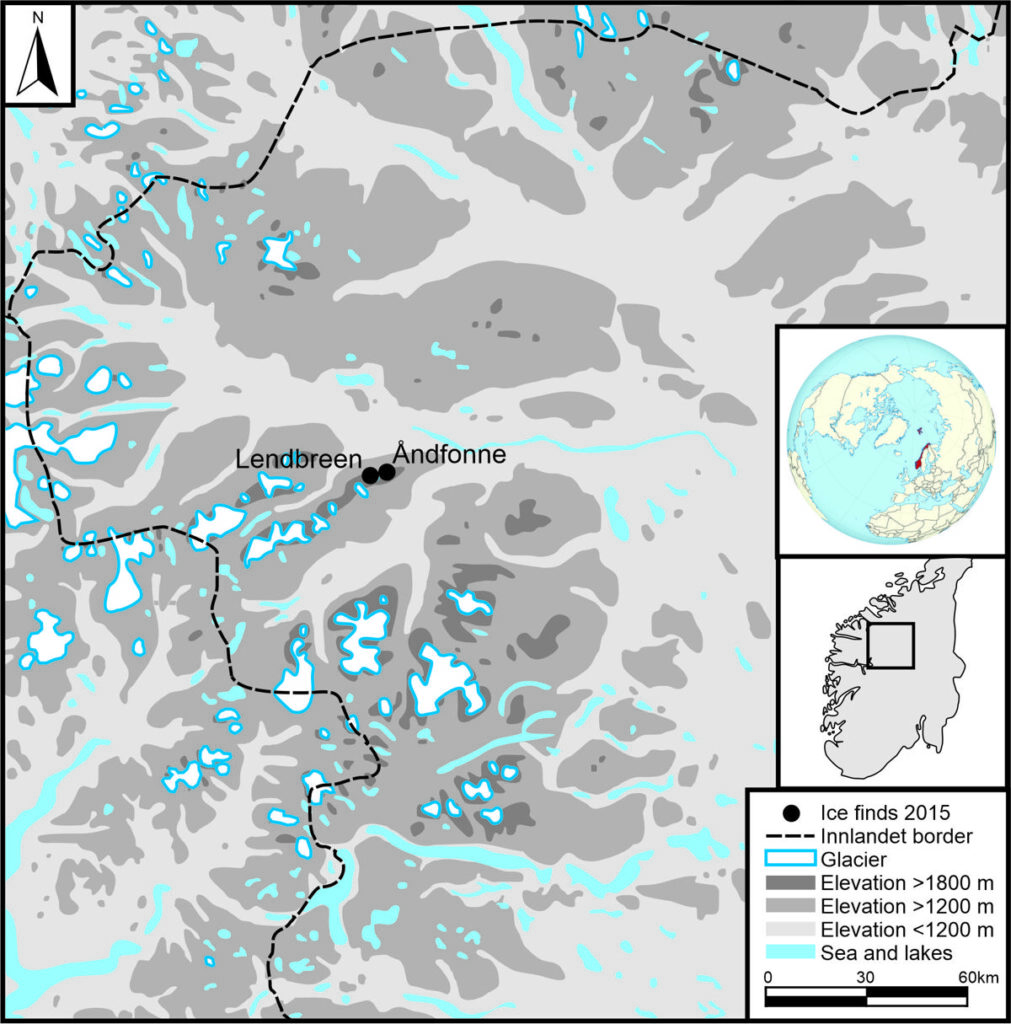

Lendbreen and Åndfonne – and still more snow

At last, on 31 August, two weeks behind schedule, we set off for our campsite below the Lendbreen ice patch. Winter snow still blanketed the site, and the chances of new artefacts melting out looked slim.

Luckily, some artefacts from earlier melt-outs still lay exposed at the Åndfonne site. Early the next morning, we hiked the hour-long route from our Lendbreen basecamp to reach it. There, we recovered a good number of scaring sticks. The plan was to return the following day to continue the work.

Photo: secretsoftheice.com.

But it was not to be. A snowstorm swept across Lomseggen during the night. The wind howled, and fresh snow quickly buried both terrain and artefacts, bringing all survey work to a stop. We spent the following day stuck in our tents, waiting for the weather to clear.

The old trail

On day three, the wind finally calmed, and we could leave the camp. Conditions on the ice were still poor, with scattered patches of snow making survey work difficult. Fortunately, we had a backup plan. In case of bad weather, we had prepared important off-ice tasks.

Earlier in August, Espen and Reidar began mapping trail markers along the route between the Lendbreen pass and Netoseter. They discovered several marked trails, with the most significant descending the south side of the Lendbreen pass. On days three and four of our fieldwork, we focused on documenting the Lendbreen trail and its markers in detail. Linking the Lendbreen pass site to the wider landscape gave a whole new meaning to the many finds there.

The weather forecast showed no more snow melting ahead, so we decided to wrap up the 2015 fieldwork a little early. It was a short field season with fewer finds than hoped, but that is part of the unpredictable nature of glacial archaeology.

If you want to learn more about the Lendbreen trail and the incredible discovery waiting at its end, check out this story.

Outreach and experimental archaeology

The 2014 discovery of a 1,300-year-old ski at Digervarden opened an exciting opportunity. We were invited to take part in an international ski festival in Altay, China, in January 2015. The Altay Mountains are perhaps the last place in the world where traditional skiing remains a living culture. Elsewhere, modern skis and techniques have replaced the old ways.

The ski seminar at the festival was a mixed bag of presentations. The Chinese were eager to assert that skiing originated in China, basing their claim on a rock painting of uncertain age. They confidently declared it to be ten thousand years old, without any solid evidence. Keep in mind, this was a couple of years before the Beijing Winter Olympics. Later research dated the painting to no more than 4,000 years ago, which is younger than the earliest known skis found in Russia and Scandinavia. The truth is, we still don’t know exactly where skiing began—or whether it was invented independently in several places.

However, witnessing traditional skiing in Altay was truly fascinating, and we made many valuable contacts. We invited some of the skiers and officials to visit us in return. The Altay delegation arrived in November 2015. The highlight of their visit was an experimental archaeology session, where Ma Liqin, one of the traditional skiers, tested a reconstructed pair of skis based on the 2014 Digervarden find. The experiment was a great success, thanks in large part to Ma Liqin’s excellent skiing skills. He suggested that the original skis were likely fur-lined, just like the traditional Altay skis.

On 17 June 2015, the Norwegian Crown Prince Haakon Magnus officially opened a new exhibition of our glacial archaeological finds at the Norwegian Mountain Centre. He also inaugurated the upgraded Climate Park on the same day. The outreach area now featured new information posts and an automatic weather monitoring station, enhancing the visitor experience.

Summing up

The 2015 field season brought unusually heavy snow and little ice melt, resulting in few new finds melting out of the ice. Despite this, important work was carried out documenting ancient trail markers near Lendbreen. Internationally, our discovery of a 1300-year-old ski in 2014 led to our participation in a traditional ski festival in the Altay Mountains of China, and an experimental test of a reconstructed ski back in Norway. At home, we opened a new exhibition of glacial finds at the Norwegian Mountain Centre and expanded the outdoor Climate Park, officially inaugurated by Crown Prince Haakon Magnus. Even in quiet years, glacial archaeology continued to move forward — both in the mountains and beyond.