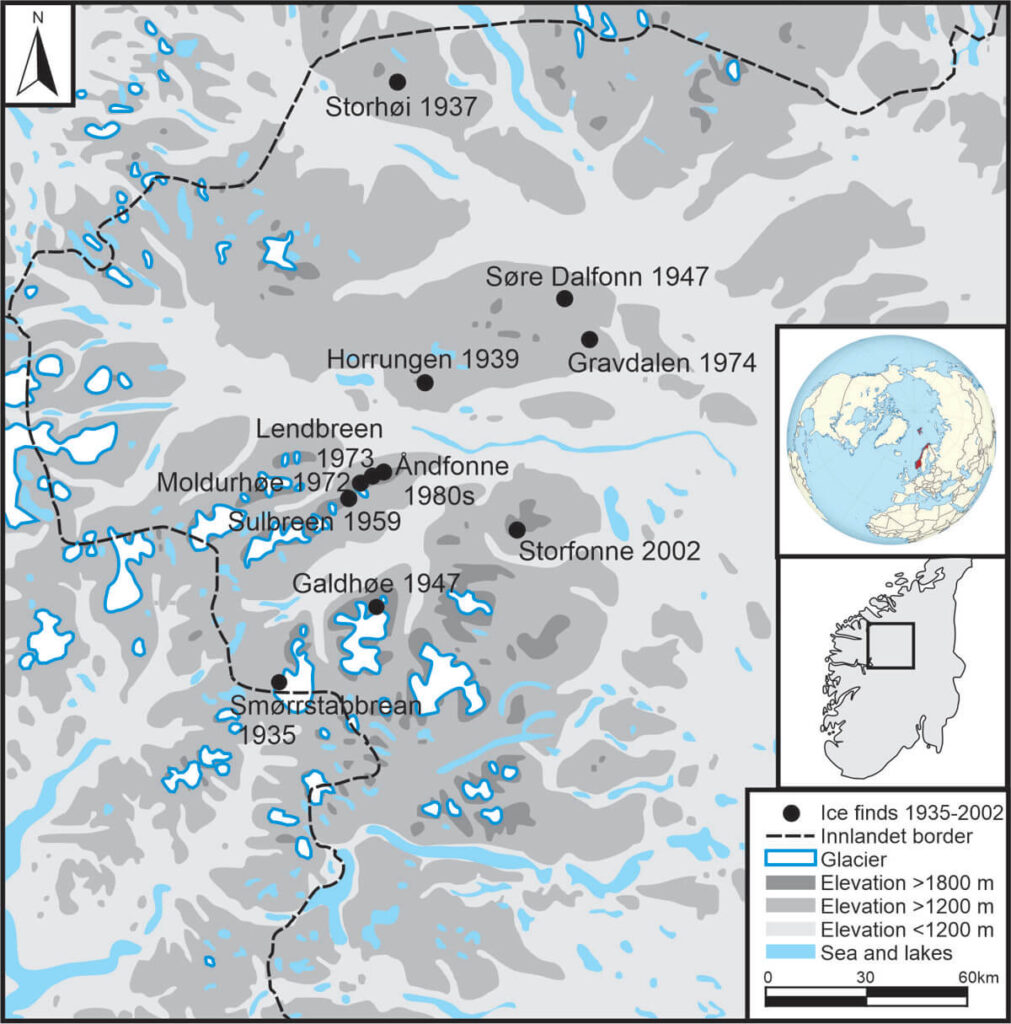

It was the big melt in 2006 and the many archaeological finds emerging from the glacial ice then, which made us aware that something was going on in our high mountains in Innlandet County, Norway. However, Innlandet has a trickle of ice finds earlier than 2006, going all the way back to 1935. In this post, we take a closer look at them.

Before we examine the first finds, let us look at the recent climate history of the high mountains of Innlandet County for context. During the Little Ice Age (approximately AD 1450-1750), glaciers and ice patches in this region were significantly larger than they are today. The size of the ice around 1750 was at its largest since the early Holocene, 10,000 years ago. During the Little Ice Age, the ice either still embedded artefacts within it or buried them beneath thick ice layers. After the Little Ice Age ended, the glaciers stopped expanding and a slow retreat commenced.

In the early 1910s, a brief warming period led to the melt-out of the first artefact from the ice in Oppdal, just north of the Innlandet County border. This marked the first recorded archaeological find from ice worldwide, but it was just a blip. The size of the glacial ice was still large.

The 1930s and 1940s

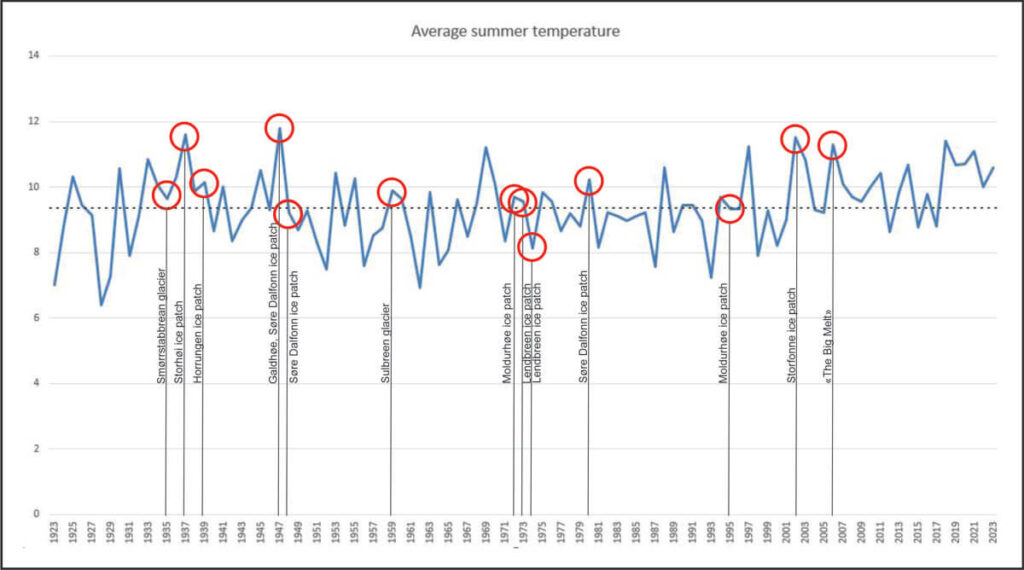

The 1930s experienced a more prolonged warming period. This resulted in additional discoveries in Oppdal and the first finds emerging from the ice in Innlandet County. We can see a clear correlation between annual summer temperatures and the earliest reported finds from the ice here in Innlandet. In addition to summer temperatures, winter snow plays an important role for the ice melt. Unfortunately, there are no continuous data for winter precipitation from our area this early.

Smørrstabbreen Glacier 1935

The first ice find from Innlandet County was a large Viking Age arrowhead discovered in 1935. A mountain hiker found it in front av the Smørrstabbreen glacier in Jotunheimen, in an area newly exposed by melting. This find included no mention of an arrow shaft, which should not surprise us. Smørrstabbreen, a large, moving glacier, likely crushed the fragile shaft in the ice. The iron arrowhead remained preserved due to its greater internal strength.

Glaciers don’t link finds as clearly to annual temperatures as ice patches do. They react more sluggishly to changes in weather and climate. Also, moving glaciers transport finds downhill with the ice to the glacier mouth and dump them there. This is a process very different from that of ice patch finds (explained here). This movement is happening even during relatively cool summers.

Mount Storhøi 1937

Mountain hikers found two arrows and an iron arrowhead near Mount Storhøi in Lesja municipality during the very warm summer of 1937. Archaeologist Bjørn Hougen at Universitetets Oldsaksamling, the archaeological museum in Oslo, wrote about the finds at the time:

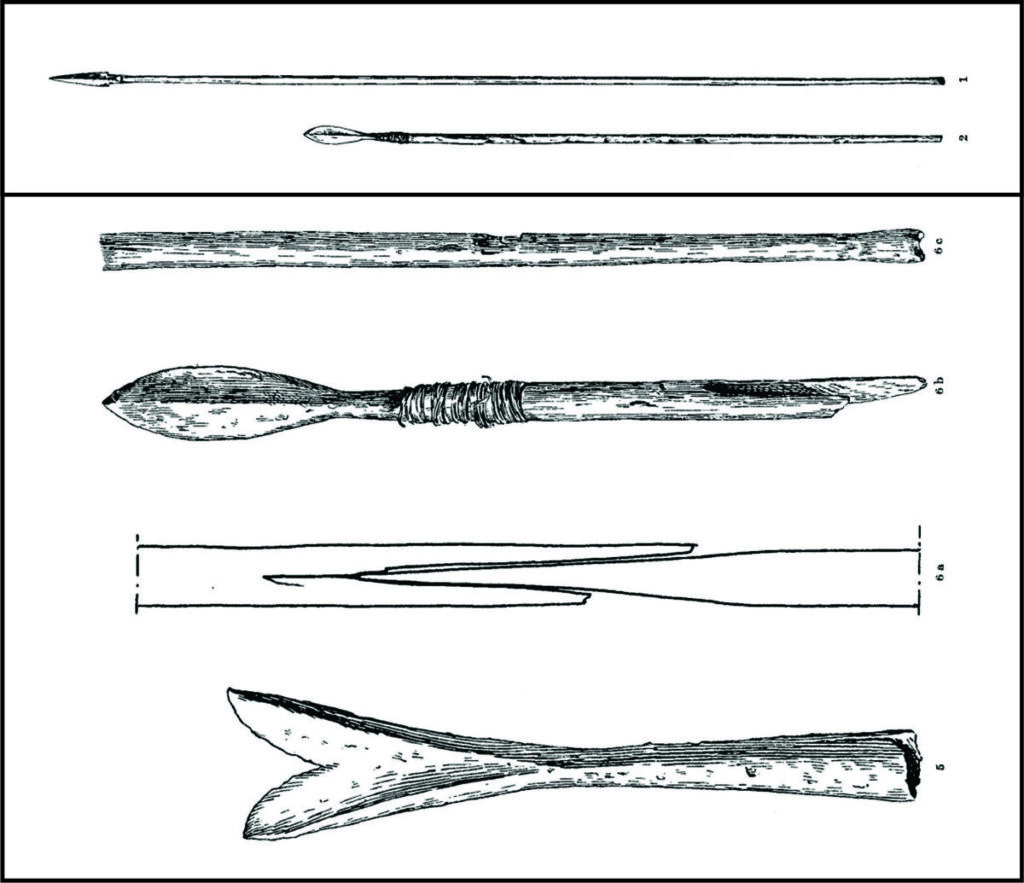

“One day in August 1937, hotel owner Michael Thøring from Lesja and his twelve-year-old son were in the mountains and ascended Mount Storhøi on the steep northern side where people rarely go. When they were about 20 minutes from the top, the boy spotted the cleft iron arrowhead (…). It lay on the bare rock near a stream and about 100 meters from the nearest snowdrift. Shortly after, the father found a long and surprisingly well-preserved arrow shaft with an accompanying bone tip lying loose beside the shaft (…). It also lay on bare rock near a stone. 20 meters further down, they found another arrow (…); this one was equipped with an iron tip and was stuck diagonally into the ground – a clear reminder of a missed shot from a distant past. The distance from these two arrows with preserved wooden shafts to the glacier was about 500 meters.”

Examining aerial photos of the area reveals two ice patches where the arrows could have been discovered.. One patch is located just 300 meters northeast of the Storhøi mountain top. However, this does not align well with a 20-minute walking distance to the summit. The other ice patch lies lower in the terrain, approximately 800 meters from the mountain top as the crow flies. This corresponds better with the 20-minute walking distance. Additionally, this area features a stream, and a small glacier located 300-400 meters further southeast, which also fits the description of the find spot. Mountain hikers found an 11th-12th century wooden spade in this area in 2018.

Radiocarbon dating conducted by the Secrets of the Ice program has revealed that the arrow with the bone arrowhead is approximately 2000 years old. The iron-tipped arrow, which has a foreshaft and a main shaft and preserved animal sinew, is dated to be around 1300 years old, based on the shape of the arrowhead. Additionally, the forked iron arrowhead, which was found without a wooden shaft, is identified as belonging to the Viking Age. So, while Hougen was wondering in his 1937 paper if all the finds where from the same hunt, we can now say with confidence that they were not. As is usually the case with ice patches, the finds are accumulations over time, not single event assemblages.

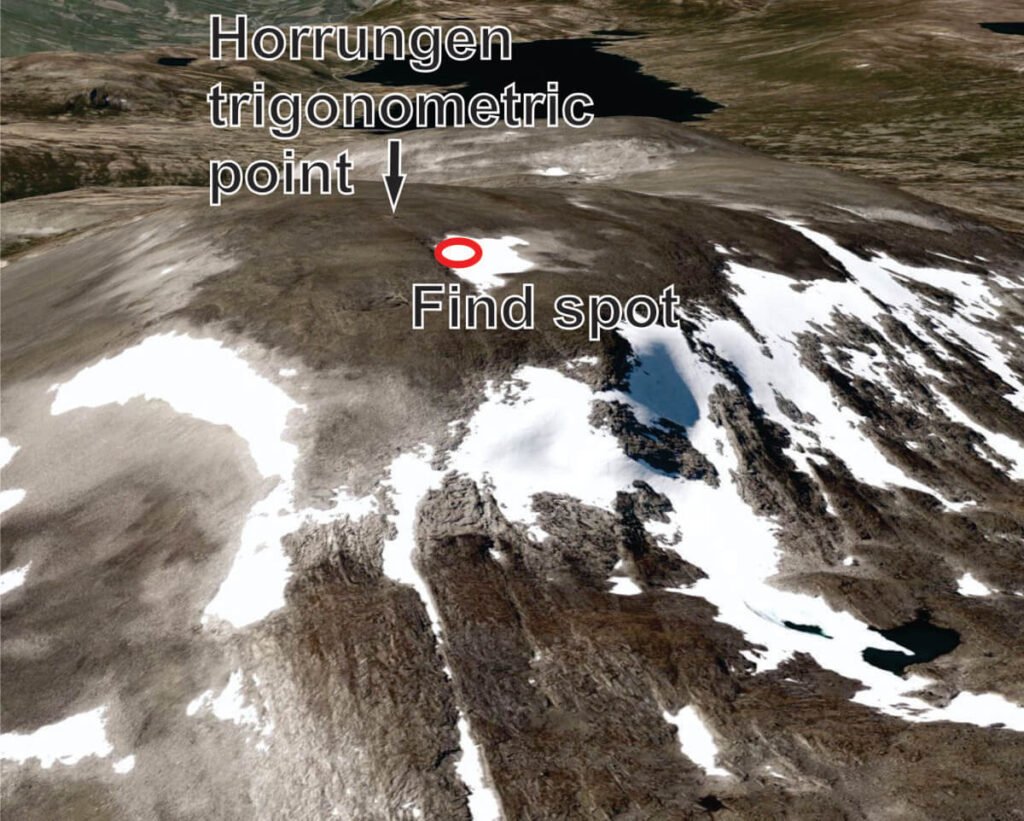

Horrungen 1939

Two years later, in 1939, an additional arrow was reported to the archaeological museum in Oslo. This was another summer with above average summer temperature, though not as warm as 1937. The arrow has an iron arrowhead and there are remains of preserved sinew where the arrowhead enters the wooden shaft. The back end with the nock is missing. The shape of the arrowhead tells us that the arrow is around 1300 years old.

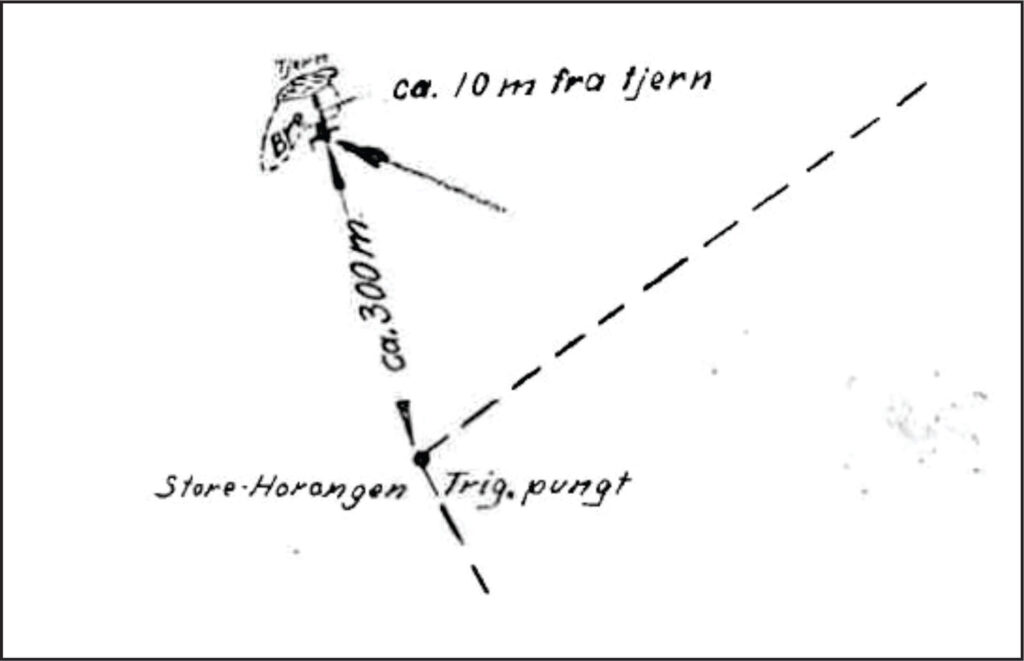

The museum catalogue states that:

“Found on Lamshorongen (c. 1900 m.a.s.l.) in the mountains between Skjåk and Lesja. The arrow lay c. 300 m from the trigonometric point of Store Horongen, by a small lake, which would probably not be visible except when there is a snow-free summer. By the lake, there is also a small glacier, and the arrow lay by the edge of the glacier, by the skeleton of a reindeer.”

“Lamshorongen” is a misspelling in the museums catalogue for Lomshorongen. This is an older name for Mount Horrungen (1,834 m.a.s.l.), located on the border between Skjåk and Lom municipalities. We have a copy of the original letters from the finder. It includes a hand-drawn a map of the find spot.

The finder Egil Mølmen was in the area to conduct land measurements. With his professional background, we can rely on the information in his map.

Our survey of the find spot in 2010 did not yield any further artefact finds near the ice patch with the 1939 arrow find.

Mount Galdhøe 1947

After World War II, mountain hikers reported new ice finds in 1947 and 1948. The summer of 1947 set a temperature record that has not been beaten since, even with the current warming.

In 1947, a mountain hiker discovered a 1,300-year-old arrow with a preserved shaft and iron arrowhead at the edge of the ice at Mount Galdhøe (2,283 m.a.s.l.). He also found an isolated iron arrowhead 40 to 50 meters away from this location.

The description of the find spot for the artifacts is brief, leaving several possible locations. Mount Galdhøe is the highest and southernmost point on a long ridge over 2,200 meters in elevation, extending 3 kilometers to the north. There is an ice patch just northeast of Mount Galdhøe, which is a possible find spot. Below Galdhøe lies the large Styggebreen glacier, which might not seem a probable find spot due to ice movement. However, mountain hikers found a piece of textile, probably from the Iron Age or medieval period, 125 meters out on the ice here in 2014. This suggests that non-moving ice is present here, although the wind could have blown the textile there more recently.

There are at least three additional potential find spots in the area: the upper edge of the Vesljuvbrean glacier and an unnamed ice patch just north of this glacier. It might even include the Juvfonne site north of the lake. Overall, the most likely candidate for the find spot remains the ice patch just below Mount Galdhøe.

Søre Dalfonn 1947-48

At the same time as a mountain hiker discovered the Galdhøe relics, another hiker found two additional arrows further north at the Søre Dalfonn ice patch in Lesja municipality. Søre Dalfonn is a canyon ice patch, situated in a long, narrow gully extending from north to south. The northern, lower section was once larger and thicker, resembling a more typical ice patch, but it melted away in the 2010s. This ice patch is located at a relatively low altitude of approximately 1600 meters above sea level. The canyon-like topography allows for the retention of permanent ice at this low elevation.

A mountain hiker made the first significant find at Søre Dalfonn in 1947 when he discovered a crossbow bolt in the southernmost part of the gully, just 2-3 meters from the ice edge. This artefact features an iron arrowhead with a socket and a thick, short shaft, measuring 51 cm in total length.

In 1948, the hiker discovered another arrow on the site. This arrow is characteristic of those used between 300-600 AD, featuring an iron arrowhead with a flat tang. Although broken into three parts with the back end missing, the arrow still retains some of the original pitch used to fasten the arrowhead. The hiker found it near a snow patch that extended at a right angle from the main ice patch in the canyon.

An Isolated Ice Find from 1959

After the 1948 Søre Dalfonn find, mountain hikers reported only one additional find from the Innlandet ice until 1972. An examination of temperatures during the 1950s to the 1990s reveals that there were occasional warm summers but no prolonged warming periods.

In 1959, local schoolteacher Gregor Kummen send a letter to the archaeological museum in Oslo to report an archaeological find. He had discovered an archaeological find at the edge of the Sulbreen glacier. The letter included a drawing of a 93 cm long stick with a thread attached to the top. We can now easily recognise the drawn object as a scaring stick. The letter is dated September 2 1959, that is during the best period discovering finds near the ice. This suggests that the find was made the same year the letter was written.

The 1970s and 1980

Moldurhøe 1972

High school student Per Dagsgard discovered what from his description was a scaring stick at Mount Moldurhøe on the Lomseggen mountain range in 1972 and reported the find to the archaeological museum in Oslo. An accompanying letter contains a hand-drawn map that shows that the find spot is the ice patch in the northern slope below Moldurhøe. Scaring sticks have since melted out in large numbers at this ice patch.

Scaring sticks were an unknown quantity in 1970s. The archaeological museum could not determine what someone had used it for or how old it was, so they returned it.

It was the reindeer researcher Øystein Mølmen, who solved the question of function of the sticks. He led a large project which mapped ancient monuments related to hunting in the Innlandet mountains in the 1970s. He found a depiction of similar objects in a 1741 book on Inuit reindeer hunting in Greenland. Mølmen quickly realized that people had used these objects both in Greenland and in Innlandet for the same purpose. They placed them in lines to guide the reindeer towards the hunters or towards pitfall traps. He radiocarbon-dated the scaring stick from Moldurhøe, and the result returned a date of c. 600-800 AD. The wooden stick had been used during Iron Age reindeer hunting!

Lendbreen 1973-74

Lendbreen ice patch, which was later to become our most famous site, appeared in the finds record for the first time in 1973. A Viking Age arrowhead was discovered there.

The report of the arrowhead found at Lendbreen sent young student Per Dagsgard on an artefact hunt at the ice patch in 1974. He made an incredible discovery – a complete Viking Age spear in front of the ice patch.

It is interesting to note that Dagsgard also reported other finds from Lendbreen (such as sled remains and scaring sticks) in his letters to the museum, to which he got no response. Maybe the archaeologists thought these objects were of a more recent date. If they had checked up on these finds, the glacial archaeology of Innlandet could have started 30 years earlier than it did.

Gravdalen 1974

In 1974, a mountain hiker made a remarkable and mysterious discovery in the Gravdalen Valley: a rare iron sword dating back to the early Pre-Roman Iron Age, around 400-300 BC. According to the museum catalogue, the hiker found the sword “in an area usually covered in snow and almost devoid of vegetation, on the lower slope of a small glacier.”

Due to the exceptional nature of the discovery, a museum archaeologist and the person who found the sword attempted to revisit the site soon after the discovery. However, bad weather thwarted their plans. In 2015, we contacted the finder again and arranged for a new visit, this time with our long-time local collaborator, Reidar Marstein. Unfortunately, the attempt was unsuccessful. Forty years had passed, the ice had receded, and the landscape had changed a lot.

In recent years, mountain hikers have found a few arrows in small ice patches in the same area. This indicates that people hunted reindeer there in prehistoric times. However, it’s puzzling why someone would bring a sword to a hunt—it doesn’t make sense. Local folklore claims that someone once found a helmet standing on a stone near the place where the hiker discovered the sword, which is even more intriguing. If it was indeed a helmet, it has since vanished without a trace. In similar cases, supposed “helmets” have often turned out to be shield bosses when properly investigated.

We can only speculate that a Pre-Roman warrior might have died in the area, leaving the sword and possibly other items behind, but for now, that remains mere conjecture.

Lendbreen 1970s and -80s

There were further finds reported from Lendbreen in the 1970s and 1980s. A 150 cm long wooden stick was collected and handed in to the museum in connection with a extensive program of mapping ancient hunting monuments connected to reindeer hunting. We do not know the exact year the stick was found, but the mapping took place from 1975 to 1978. Half of a possible bow made from hazel was also recovered from Lendbreen, as were scaring sticks.

In the 1980s, a Viking Age arrowhead was found at Lendbreen . The find circumstances were described as “ .. found on the surface, near the edge of the glacier”

Small fragments of a wooden spade (C53146) were found at Lendbreen in the early 1980s. We have radiocarbon-dated the spade to the Migration Period.

Åndfonne

Åndfonne ice patch, close to Lendbreen, appeared on the radar for the first time in the 1980s. Five wooden flags for scaring sticks were found in a bundle here.

Søre Dalfonn 1980

We have already heard about the first finds from the Søre Dalfonn ice patch in 1947-48. In 1980, a report came of another find from this ice patch: The front part of a ski. This ski would prove to be the first of several ski finds from the Innlandet ice.

The preserved length of the ski is 89 cm. Because the binding area is not preserved, we can infer that the ski was likely at least 2 meters long. There is a raised ridgeline along the top of the ski.

The 1990s until 2002

A mountain hiker found a wooden spade in the ice at Mount Moldurhøe in 1995, and Dagsgard reported it in his book on ancient monuments in the Lomseggen mountain range, published in 2000.

Around this time, hobby archaeologist Reidar Marstein from Lom started visiting the Storfonne ice patch in the Kvitingskjølen mountain range. He had a hunch that there could be archaeological finds here, like the ones previously reported from Oppdal, just north of the Innlandet county border. He didn’t give up, even after several years without making finds. However, the conditions with ‘large ice’ were working against him. Then global warming started to impress itself upon the Innlandet mountain ice.

2002-2003 – First Finds at Storfonne

The early 2000s marked the beginning of a marked and sustained retreat of ice in the high mountains. Especially 2002 stands out as a year with a very warm summer. This was also the year when Reidar’s efforts finally paid off. He found a scaring stick near the edge of the Storfonne Ice Patch and reported the find to the county archaeologists. The radiocarbon-date showed that it was 1300 years old, much the same date as the scaring stick Per Dagsgard had found at Moldurhøe in 1973. Little did we know at the time, that this was just the beginning of a new and dramatic wave of ice finds here in Innlandet.

Reidar returned to Storfonne in 2003 and found more scaring sticks. In 2004 and 2005, there were no further finds due to too much snow.

Summing up

There were quite a few finds from ice patches in Innlandet County prior to the big melt in 2006. Most of the pre-2006 finds were related to Iron Age and Viking Age reindeer hunting, such as arrows, arrowheads, and scaring sticks. Even with a limited number of finds, Lendbreen ice patch stood out as something different.

There were no systematic surveys for archaeological finds from the ice prior to 2006. Mountain hikers mainly made the finds coincidentally. The exceptions are the finds from Søre Dalfonn, Lendbreen and Storfonne. At Søre Dalfonn, local knowledge about the archaeological potential of the site following the 1947 find likely led to the additional finds. Dagsgard also knew about the presence of finds at Lendbreen before he discovered the Viking Age spear there. Reidar deliberately targeted Storfonne to look for archaeological finds.

Most finds are from years with warm summers, but not all. Since people made finds during summers with normal or even colder-than-normal temperatures, it seems reasonable to conclude that finds lay out in the open without being reported before the sustained melt and further ice retreat began in 2002. There was little public awareness of archaeological ice finds in Innlandet prior to 2006, and no systematic search for artefacts near the ice.

This was all about to change in 2006.

For a short overview of early finds outside Norway, check this post