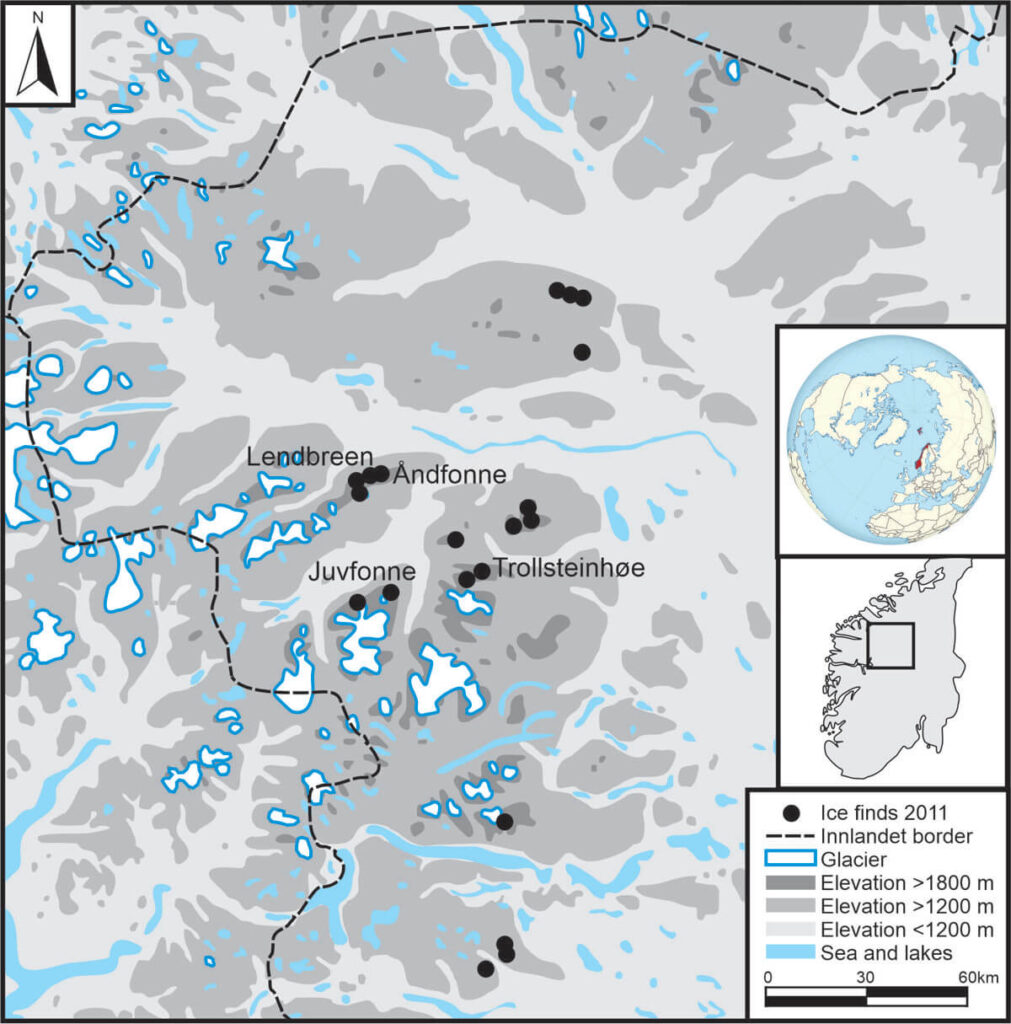

In 2011, we received permanent funding for our Glacier Archaeology Program in Innlandet County. This was a huge relief. Securing permanent funding marked a turning point for glacial archaeology in Innlandet, even though it came with its own set of challenges. The funding amounted to only half of what we had estimated was necessary to cover the costs of fieldwork and finds processing. Still, it allowed us to send out a permanent team to explore sites during what turned out to be an exceptionally long field season with heavy melting. We began fieldwork on August 1, and the last day in the field was on October 1.

The team conducting exploratory surveys consisted of Elling Utvik Wammer, Julian Post-Melbye, and our longtime local helper, Reidar Marstein. Julian joined us in 2011 as an intern and has been part of the program ever since.

In addition to exploratory surveys, we undertook two major systematic surveys with a larger crew. In total, we targeted 20 sites, nine of which were new discoveries. The field effort marked a significant increase compared to previous years. The finds came in fast and in large numbers, so much so that they exhausted our initial funding early. Nevertheless, we decided we could not leave any finds behind, even without funding to process them. Fortunately, we were able to secure additional government funding for 2011 due to the many spectacular discoveries.

In this post, we will concentrate on the most important fieldwork of 2011.

The Lost Mountain Pass at Lendbreen

The first fieldwork in 2011 was a large systematic survey of the Lendbreen ice patch. Lendbreen had delivered many previous finds, going back to the 1970s. The finds, which included a complete Viking spear, differed from the other sites, and that made Lendbreen an obvious first target.

The team of five archaeologists hiked to the base camp at the foot of the ice patch on August 1, with packhorses carrying most of the equipment and food. Survey work began on the western side of the ice patch, moving uphill and then along the upper edge toward the east. We documented and collected animal bones and a few artefacts. After three days, it seemed we would be able to complete the survey by the end of the week. How wrong we were.

On Thursday, August 4th, we made an incredibly discovery – a lost mountain pass. You can read the rest of the story here.

Åndfonne Ice Patch

We had a long stay at the Lendbreen basecamp during the early August fieldwork and this made it possible for us to undertake a systematic survey at nearby Åndfonne ice patch as well. We documented and collected two well-preserved arrows with iron arrowheads, and a lot of scaring sticks.

When we returned to Åndfonne for a one-day survey in September, we found a bow as well. A radiocarbon-date revealed that the bow was 3,300 years old, from the Early Bronze Age. At the time, it was the oldest known bow from Norway, but later, a Late Neolithic bow would beat that record when it melted out of the Lendbreen ice.

Double ice mass in Jotunheimen

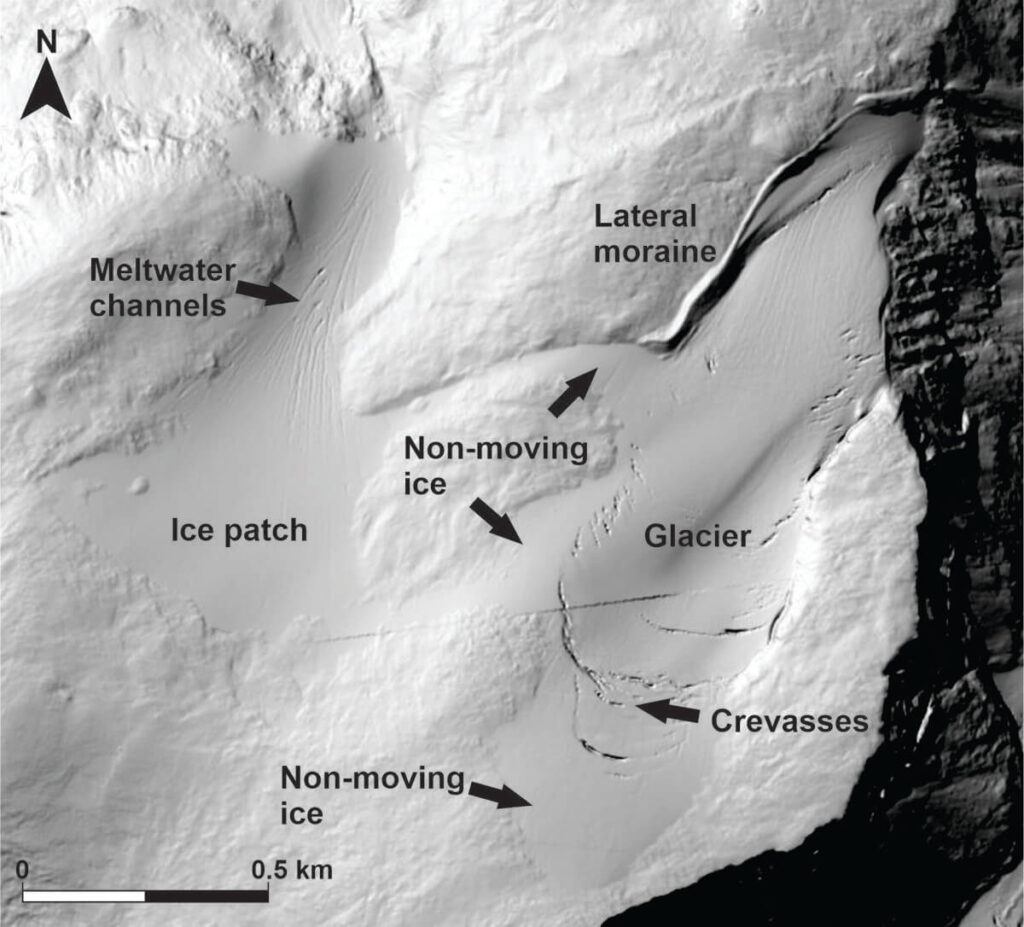

In mid-August, Elling, Julian, and Reidar conducted an exploratory survey targeting a large double ice mass in northern Jotunheimen. One part of the ice mass was a glacier, with its upper section consisting of stationary, non-moving ice. The team found no artefacts in this area.

The second ice body was an ice patch, connected to the glacier by two narrow strips of ice. Although the ice patch did not yield many finds, the team recovered a particularly well-preserved Early Iron Age arrow, complete with four fletches.

The terrain leading to the double ice mass was difficult and demanding to hike through, which may explain the scarcity of finds in the area. Most sites with significant numbers of finds tend to be easily accessible from the valley below—this one, however, was not.

Finding a suitable camping site on the hillside below the ice also proved challenging.The GPS inaccurately indicated that the team was much higher than they actually were, further complicating matters. Ultimately, the team had to set up camp on a sloping hillside.

After a long and strenuous day at the ice, the team returned to the camp in the dark. Unfortunately, they didn’t get much sleep, as they kept sliding into the lower part of the tent throughout the night. Overall, it was an exceptionally demanding ice site, and we have returned only once since, without discovering any additional finds.

Trollsteinhøe

At the end of August, Elling, Julian, and Reidar embarked on a two-day exploratory survey into the Trollsteinhøe massif in Jotunheimen. This massif was home to one previously known site, where Reidar had earlier recovered a Viking Age arrow.

I was in my office when my mobile phone rang. It was Elling, although the connection was poor. I could only make out fragments of his excited words, accompanied by shouts of joy in the background. Then, the line cleared: “There are hundreds of them. Hundreds!”

They had discovered a new site with scaring sticks—an incredible find. The ice patch was so small that it wasn’t even marked on the map, yet it contained hundreds of artefacts. On that day, they sketched the site and carefully noted the areas where the finds concentrated. They also collected samples of the scaring sticks, as these were the only visible artefacts.

We returned to the site in 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2019. During those visits, additional types of finds emerged, including arrows, a walking stick, and a beautifully crafted Iron Age knife.

An Early Iron Age Arrow

In addition, the team explored a nearby glacier, where they discovered a complete Early Iron Age arrow. Normally, glaciers do not preserve archaeological finds older than 500 years. However, in this case, they recovered the arrow from non-mvoing ice in the upper part of the glacier .

This discovery brought the number of sites in the Trollsteinhøe massif from one to three—not bad for a two-day survey!

A New Ice Site in the Kvitingskjølen Massif

A week later, Elling, Julian, and Reidar went on a day hike to an ice patch in the Kvitingskjølen massif, located just across the valley from Trollsteinhøe. Reidar had previously visited the ice patch without observing any finds. However, the significant ice melt in 2011 had severely affected this patch, separating it into five ice individual patches. As soon as the team reached the ice, they began discovering artefacts.

They found eight arrows during their visit. Two weeks later, Reidar returned to the site and recovered an additional six arrows, bringing the total to 14.

Local mountain hikers also recovered and reported a bone arrowhead and a whetstone from the ice patch that same year.

The 2011 finds at this ice patch, which had previously yielded no artefacts, show that one should not dismiss ice patches based on a single visit. They may not have melted sufficiently yet for the artefacts to emerge.

The earliest arrow recovered from this site in 2011 dated to the Early Bronze Age. We have returned to this ice patch several times since, including conducting a systematic survey in 2013.

The Viking Age Cargo Net

Jostein Bergstøl, project leader for the ice finds at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo in 2011, participated in some of the fieldwork at Lendbreen and Åndfonne. He also has a cabin in the southern Jotunheimen mountains, from where he regularly explores the surrounding area. Over the years, this has led to a series of discoveries from ice patches.

In 2011, Jostein made a remarkable find at a small ice patch that otherwise yielded no artefacts. He discovered a net made of leather strings attached to wooden sticks. Upon closer inspection, we identified it as a cargo net for packhorses. Radiocarbon dating confirmed its origins in the Viking Age. The cargo net not only sheds light on packhorse transport but also provides rare evidence of everyday life in the Viking Age, making it an unparalleled discovery!

The Climate Park

The significant melt in 2011 yielded a lot of archaeological finds but also marked the end of the ice tunnel constructed in the Juvfonne ice patch in 2010. By mid-September, it had to be abandoned. Plans for a new, deeper tunnel were immediately set in motion, as the Climate Park at Juvfonne relied on the tunnel for its outreach efforts.

The southern part of the Climate Park at Juvfonne features a large moraine. Beyond the moraine lies a small glacier, nestled within a stunning but challenging-to-access landscape. To improve accessibility, Sherpas from Nepal constructed an impressive path through the moraine, leading to a vantage point where visitors can take in the breathtaking views.

In 2011, the Climate Park and the Mountain Museum were honoured with an award from the Finse Foundation (Finsefondet) for their public outreach efforts in glacial archaeology and raising awareness about climate change.

Exhibitions

In September 2011, the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo opened a temporary exhibition called “The Archaeology of Ice“, showing many of the finds recovered from the ice in Innlandet County. The exhibition was open until the end of January 2012.

During the 2011 fieldwork, a selection of our finds were exhibited locally in a refrigerated display case at the Mountain Museum in Lom.

Summing Up 2011

We secured permanent funding for our glacial archaeology efforts just in the nick of time. The year 2011 brought significant ice melt, allowing us to visit 20 sites in August and September. We documented and collected nearly 800 finds, setting a new record. The exceptional discoveries of 2011 underscored the importance of continued research and funding to safeguard glacial archaeology amid accelerating climate change.

The discovery of the lost mountain pass at Lendbreen was the highlight of 2011. This site would yield many more finds in the years to come and provide crucial insights into ancient life in the high mountains of Innlandet.

However, the sheer number of new sites and artefacts left us concerned about whether we were adequately prepared and funded to handle such a rapid pace of discoveries if the melting continued at 2011 levels. What would 2012 bring?

You can find previous posts about the history of the program here.