How do glacial archaeologists know the dating of artefacts found in the ice? There are a number of dating techniques available to archaeologists. We use two main dating techniques in glacier archaeology – typological dating (the shape of the artefact) and radiocarbon dating.

Typological dating

Typological dating used to be the only available absolute dating technique for archaeologists. It works as follows: Historical sources or coins with a known date can sometimes be linked with archaeological artefacts of specific types. These artefact types may again be linked with other artefacts types, e.g. in graves. By studying how such artefact types appear together, it is possible to build up large artefacts chronologies. This major groundwork was laid down by the archaeologists of the late 19th century and early 20th century. You can read more here: Typological dating

We mainly use typological dating for arrows and arrowheads in glacier archaeology. The pioneer work in this respect is Oddmunn Farbregd’s book on Iron Age and Medieval arrow chronology from 1972, based on the finds from the Oppdal Mountains in Norway.

However, most of the finds from the ice cannot be dated by typology. They are artefacts in organic materials and often unique – not found anywhere else. How can we date these?

Radiocarbon dating

In the 1940ies, the American scientist Willard Libby developed a method for dating organic materials, so-called radiocarbon dating. The basis for this dating technique is that there are different carbon isotopes present in nature. C12 and C13 are stable carbon isotopes, while C14 (radiocarbon) is a radioactive isotope. C14 is created in the atmosphere by cosmic rays. In the atmosphere, C14 combines with oxygen to make CO2, which is then incorporated in plants by photosynthesis, and subsequently in animals eating the plants, eventually reaching the entire biosphere. It was originally believed that the amount of C14 in nature was constant, i.e. that the decrease of C14 by radioactive decay was replaced by the same amount of new C14 created in the atmosphere.

When a living organism dies, the amount of C14 decreases without being replaced by new C14. The half-life of C14 is 5730 years. Thus, if a fragment of wood is measured to contain only half of the known proportion of C14 to C12, then the wood was believed to be c. 5730 years old. This principle also applies to the dating of artefacts of organic materials.

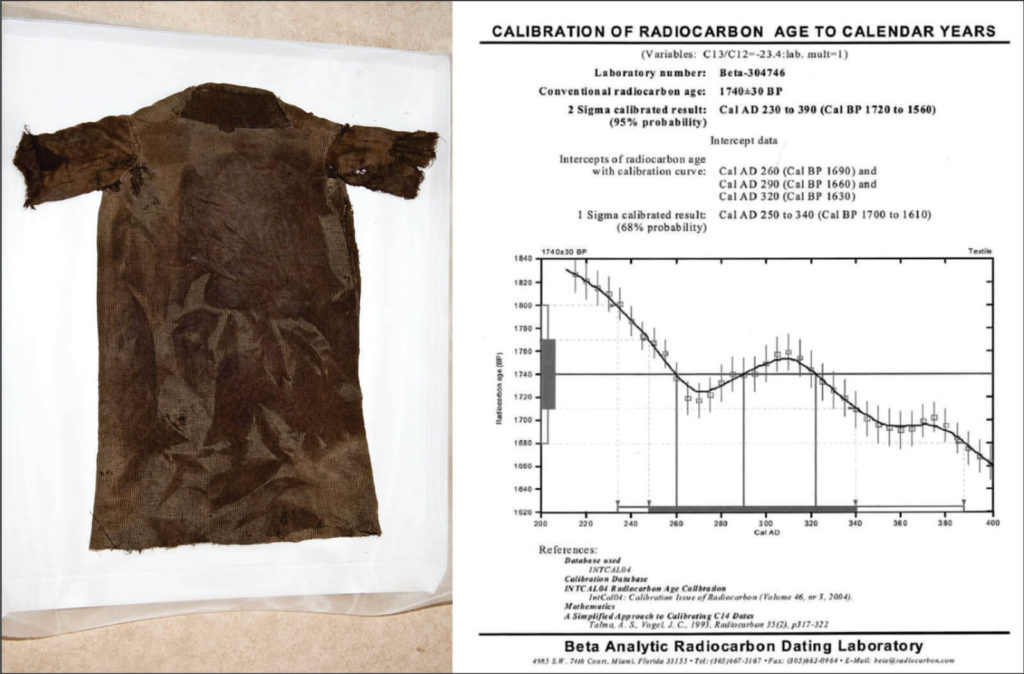

The method has been further refined and developed since Libby invented it. One very important advancement was that it was discovered that the amount of C14 in nature is not constant. This was corrected by radiocarbon dating of tree rings with a known calendar year date, using the very long-lived California bristlecone pine. This is called calibration, and in general leads to the calibrated dates (in calendar years) being older than the uncalibrated dates (in C14 years).

You can read about radiocarbon dating in much more detail here: Radiocarbon dating

When undertaking radiocarbon dating of artefacts, it is important to be aware that the date of the sample may not always tell the age of the artefact. As an example: Arrowshafts are sometimes made from split pinewood. Pine can become several centuries old, and once the annual tree-ring is formed, it no longer takes up new C14. Thus, there is a potential old-wood problem here. The date we get from the wood may be hundreds of years older than when the artefact was used. However, many objects are made of shorter-lived materials, such as birch, bark or wool, minimizing this problem.

We will be submitting a number of radiocarbon samples to provide dating of artefacts found during this field-season. However, one find has been given VIP treatment – the sled found on the first day of fieldwork. A radiocarbon sample was recently submitted to Beta Analytic in Miami and the result should be ready by Monday 8th of this month. The sled is not datable by type, but it has an iron nail. This makes it likely that it is younger than 2000 years, which is when iron started to be commonly used in Norway. At the same time, very few of our finds from ice are younger than the Medieval Period. We will know the result by Monday. Exciting times!