«He’s there, he’s right there”. The archaeologists stood back in shock and awe. Nothing had prepared them for the encounter with the Victorian seaman from the lost Franklin expedition, buried in the frozen ground in the Canadian High Arctic. It was like he had just died.

We take a closer look at the investigation of the Beechey Island permafrost burials. What can they tell us about the disastrous Franklin expedition, and why are they so well preserved?

The Expedition

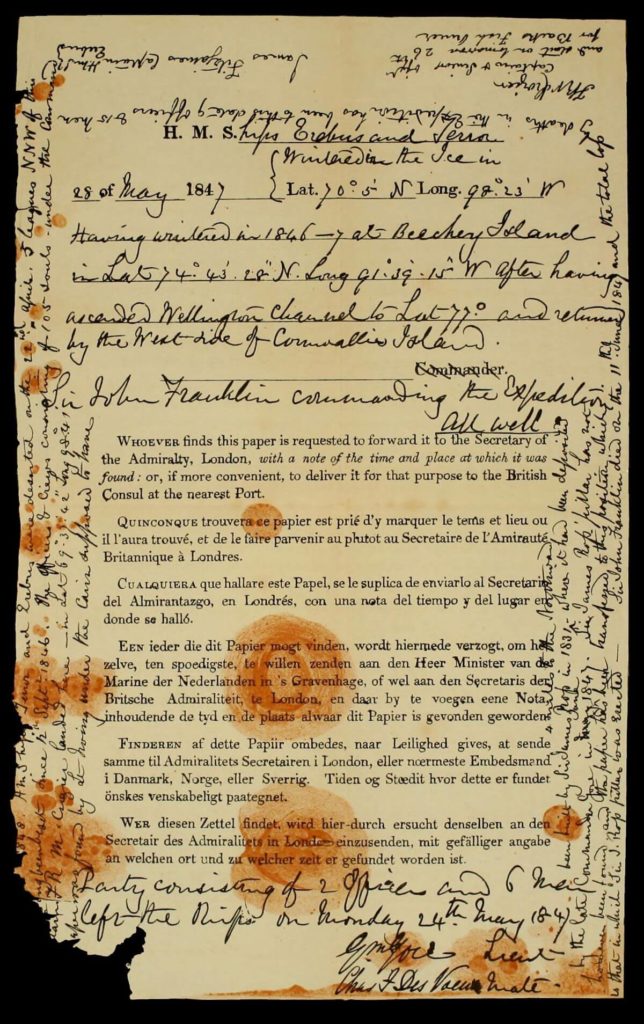

The Franklin expedition was meant to be the final exploration of the Northwest Passage – the sea route linking Europe and Asia through the Canadian Arctic. Instead, the expedition ended in a disaster. The two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, were lost with all hands. The clues to why this happened were few and mysterious. The expedition was well equipped for a long stay in the Arctic. Why did it end so badly?

The ships sailed from England in May 1845 with 134 men, under the leadership of Sir John Franklin. They were last seen in Baffin Bay in July of the same year, when five expedition members were discharged and sent home with whalers. After this, there was only silence.

Since the expedition was equipped with three years of provisions, the Admiralty in London did not send out rescue missions until 1848. By this time, most of the members of the Franklin expedition were already dead.

Intense searches in the 1850s shed light on the fate of the expedition. It had wintered on the small Beechey Island 1845/46. The wintering quarters were found, including a small cemetery with the burials of three seamen who had died during the overwintering.

The Franklin ships had sailed from Beechey Island and south through Peel Sound in the summer of 1846. Both ships got stuck in the ice off King William Island in September and the second wintering took place there. To the shock of the expedition members, the ice did not thaw during the 1847 summer. The situation was made worse by the death of Franklin on June 11 1847, according to a note later found in a cairn on King William Island.

After another wintering off King William Island, the men abandoned the ships in late April 1848. They simply could not wait another year in the hope that the ships would be released by the ice. The provisions would have run out by then and the men would have been in no state to trek south.

By April 1848, 9 officers and 15 seamen had died, according to the note mentioned above. The remaining crew tried to reach Back River and a Hudson Bay company outpost further south. They dragged along lifeboats on sleds with provisions and equipment. During this trek, the seamen encountered local Inuit. The Inuit later reported these meetings and their subsequent discovery of dead expedition members to the search parties. These reports also included information about cannibalism among the seamen.

The expedition members did not make it, leaving skeletons and artefacts scattered along the route on the western and southern coast of King William Island and on the northern coast of the mainland. Search parties in the 1850s discovered many of these remains.

The Mystery

The loss of the Franklin expedition remained a mystery. Why was there a high number of deaths early on in the expedition? Other Arctic expeditions had lost far fewer lives, e.g. James Ross Clark’s expedition in the same area from 1829-1833 with only three lives lost. Why did the Franklin expedition fare so badly? Speculations were plenty, but there was little hard evidence to provide a firmer basis for theories.

The First Forensic Work

Owen Beattie, then an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Alberta, started his work on the Franklin expedition in 1981. That year and the next, he conducted surveys on the western side of King William Island. Together with his team, he was able to recover bones from Franklin crew members. Telltale marks on the bones confirmed the Inuit stories about cannibalism. Even more interesting was the discovery of enhanced lead levels in the seamen’s bones, compared to Inuit bones recovered during the same survey.

Lead poisoning can be fatal. Enhanced levels of lead leads to a number of serious symptoms, such as joint and muscle pain, cognitive difficulties, headaches and abdominal pain. This is something you really do not want to happen while under extreme Arctic conditions.

While the enhanced lead levels were intriguing, they were difficult to use as evidence as lead normally takes quite some time to build up in bones. The high lead levels could have been a result of environmental conditions in Great Britain, and not lead exposure during the expedition. Beattie needed tissue to find out when the lead entered the bodies, preferably hair or nails.

Beattie turned his attention to the small cemetery at Beechey Island, and the three graves of the Franklin seamen there. These seamen died early in the first expedition, during the first wintering. Three early deaths were not normal during Arctic expeditions in the 19th century. Already in the 1850s, these early deaths had aroused suspicion that something went wrong from the beginning of the Franklin expedition. Maybe their bodies were preserved by the permafrost? Could the bodies yield information on their causes of death, and on their lead levels?

Beattie applied for permission to open the graves and autopsy the bodies.

Bodies from the Ice

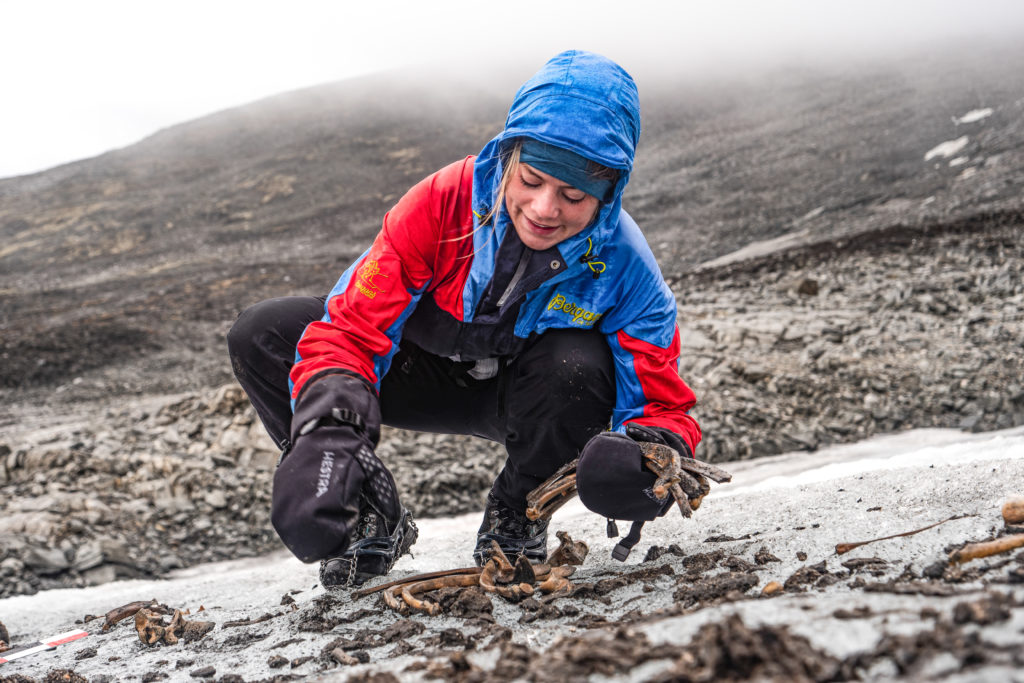

Beattie had good reasons to believe that the bodies of the three Franklin sailors could be preserved by the permafrost ice. However, not all ice preserves human bodies. Before we move on to Beattie’s discoveries, we take a brief look at human remains from ice to discuss why permafrost ice preserves so well, compared to e.g. glacial ice.

Human bodies do not preserve well in glacial ice as they are likely to be at least intermittently exposed to air. In addition, the movement of the ice tears the bodies apart. If the bodies are not very recent, they are preserved mainly in a skeletonised way, sometimes with soft tissue attached (examples here). The same goes for the bodies of animals. Ötzi is the only exception to this rule.

Preservation of human and animal bodies in permafrost is a completely different story. Burial in permafrost ice seals the body off from exposure to open air, and there is often no ice movement either. Essentially, the bodies are permanently stored in a deep freezer. Such bodies can be incredibly well preserved. That is, until the permafrost thaws, or the permafrost is mined for fossils, as happens in Siberia today.

Human burials in the Arctic permafrost are known from a number of locations. Most of the early graves are from whalers or explorers. The Inuit traditionally buried their dead above ground. The European whalers and explorers had a Christian belief, demanding a burial in the ground. In the High Arctic, this entailed hacking deep into the hard permafrost to be able to bury the dead.

Burials in the permafrost can be incredibly well preserved. If there is little melting of the uppermost permafrost layer in the summer, the burials are essentially frozen in time. If there is active permafrost movement due to freeze-thaw cycles, then burials may make their way up to the surface over time (an example here)

Human bodies from permafrost are sometimes referred to as ice mummies, but technically the bodies are not preserved by natural mummification, but by the cold. They are frozen, not mummified. This is why the recent warming of the Arctic has led to the gradual destruction of a large number of such graves. When they thaw, natural processes start decomposing the bodies.

Beattie’s idea of examining the bodies of Franklin expedition members, buried in the permafrost on Beechey Island, was a good one. However, he may have been surprised when he discovered how well preserved the bodies were.

The Cemetery at Beechey Island

Arranging for a proper exhumation in the midst of the Canadian Arctic is no small feat in logistics and permissions, but in the summer of 1984, Beattie was finally ready.

John Torrington

Beattie and his team started by opening the grave of Leading Stoker John Torrington. According to his grave marker, he died on January 1, 1846, the first seaman to die during the expedition.

Just as the original burial party would have experienced, the Beattie team found it hard work hacking their way down through the frozen gravel. Finally, at depth of 1.5 m, the lid of the coffin appeared. After lifting the lid, they could see the dead incased in a block of ice. They applied heated water to thaw the remains. This is a method we also use on our glacial sites, if artefacts are still encased in ice.

The body was incredibly well preserved, as was the clothing. John Torrington had been very ill at the time of his death. He was extremely thin, weighing only 38.5 kg. His hands were callus-free, and as he was a stoker, this tells us that he had been unable to work for quite some time prior to his death.

The autopsy, and later analysis of the samples taken, showed that Torrington had suffered from tuberculosis. The cause of death was probably pneumonia. Samples of his hair and nails revealed high levels of lead, even more so than the bones from King William Island, previously examined by Beattie. So maybe lead poisoning had weakened him, eventually leading to his death of pneumonia?

John Hartnell and William Braine

Beattie and his team returned to Beechey Island in 1986 to exhume Able Seamen John Hartnell (died January 4 1846) and William Braine (died April 3 1846). In both cases, the autopsy and subsequent analysis pointed to pneumonia, brought on by tuberculosis, just as in the case of John Torrington. There were no signs of scurvy. The level of lead in the hair and nails of Hartnell and Braine were also high, but lower than Torrington’s.

Remarkably, after removing the clothing of John Hartnell, they could see that he had been autopsied before the burial. It appeared that Harry Goodsir, the ship’s doctor (or perhaps his superiors), had been wondering why the crew had suffered two fatalities so early in the expedition.

The bodies were reburied after the autopsies, and the grave markings were reconstructed on the surface.

Beattie concluded that lead poisoning had been a significant contributor to the death of the three sailors, and probably also to the catastrophic end of the expedition. He claimed that the source of the lead in the exhumed sailors was the soldering of the cans containing tinned foods. Beattie even tried to back this up by doing isotopic analysis, showing that the lead in the hair and in the solder came from the same source.

New Theories

Beattie’s lead poisoning theory is neat, and after reading John Geiger’s book on Beattie’s work, I was sure that this had to be the explanation. However, subsequent re-examinations of samples and other historical data raise doubt that things are so easy.

What is wrong with the lead and food hypothesis? Well, first of all: How do we know that the level of lead in the three exhumed sailors was higher than normal for this group? Beattie’s study lacks a control group, i.e. other British seamen from the same period. Obviously, such a control group would be hard to find, but it is still missing. Lead levels for bones of Franklin expedition members are for example similar to samples from a Roman cemetery in Dorset, England, i.e. reflecting a high lead environment, not lead poisoning. Other contemporary expeditions also partly relied on tinned foods, without ending in disaster.

Generally, the use of lead in association with food and beverages in the 19th and early 20th century was much higher than today. The high levels of lead in bones is unlikely to be from exposure during the expedition. It reflects a “whole of life” exposure, a sink if you like.

Due to chemical processes, the leaking of lead from the solder would have been limited. This is confirmed by studies of preserved tins from the Franklin expedition. Based on the records, less than 15 % of the food supplies were canned foods. The expedition would have used the fresh food first, making it well nigh impossible for the expedition food to have been the cause of high lead levels in the bones of the three seamen.

The higher levels of lead in the hair of the dead at Beechey Island could have been caused by them living mainly on a liquid diet at the end of their lives. Many sources of drink at this time would have had a high lead content. There are no diagnostic symptoms of lead poisoning in the men, such as calcifications in the basal ganglia. The isotope analysis is deemed inconclusive, as similar values have been obtained from a number of different sources.

A later study of John Hartnell’s thumbnail, collected by the Beattie team, suggests that the high level of lead is matched by high levels of zinc and copper. It may be caused by the release of these metals stored in bones during the last phases of the disease. The medications given during the last phase could also have contributed to the high levels found.

At the moment, the conclusion is that the lead levels are not high enough to have played a major role in the unfolding of the disaster, but they may have played a supporting role. In the end, the main reason for the expedition’s catastrophic failure was the harsh climate in the Canadian High Arctic at the end of the Little Ice Age. Franklin and his men were trying to force their way through the ice-choked Northwest Passage at the worst possible time.

The Discovery of the Ships

After years of surveys, the two Franklin ships were discovered recently, Erebus in 2014 and Terror in 2016. Both shipwrecks appeared in surprising locations, away from where they were left stuck in the ice in 1848. Inuit information played a crucial role in the discovery of the ships way outside the original search perimeter off the north-west coast of King William Island.

The shipwrecks may hold important evidence that could explain what happened during the final phase of the expedition. The geographical location of the wrecks could indicate that some members of the expedition returned to the ships and sailed south, before they finally succumbed to the High Arctic conditions. That this may have happened is backed up by Inuit oral sources.

The Future of the Frozen Seamen and the Arctic

The Arctic is warming up, much more so than the rest of the globe. Where Franklin and his men once fought for their lives in the ice, cruise tourists now sail in comfort. In the decades to come, the Arctic will continue to heat up, leading to further disruption of ecosystems and increased melting of permafrost. The frozen seamen in the Beechey Island cemetery will thaw and disappear.

We will not only be losing the last remains of the Franklin expedition due to the warming. The Arctic we know will be gone. The Earth will change into a different place. We are heading into the unknown. Is there a lesson to learn from the fate of the Franklin expedition?

“The Terror” – TV series on the Franklin Expedition. Much recommended, even though Ridley Scott does take some artistic liberties.

Further reading

If you would like to read more about the Franklin expedition, I can recommend the following books:

John Geiger & Owen Beattie: Frozen in Time: The Fate of the Franklin Expedition

Gillian Hutchinson: Sir John Franklin’s Erebus and Terror Expedition

Paul Watson: Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition

David C. Woodman: Unravelling the Franklin Mystery: Inuit Testimony