If you came straight here, you may want to read our section on finding the glacial archaeological sites first.

When we find a glacial archaeological site during exploratory survey, we add it to our site list. Each year we choose among the listed sites for fieldwork. The melting situation decides which sites are chosen, and the scale of fieldwork. Ideally, we would like to do fieldwork on sites which have marked ice retreat and old ice exposed on the ice surface.

We collect information on melt and ice retreat during the summer. Local mountain hikers provide us information when they visit the sites. One site, Juvfonne, lies close to a paved road, and has a weather station near the ice. It provides us with real-time data on temperature and snow depth which is very helpful.

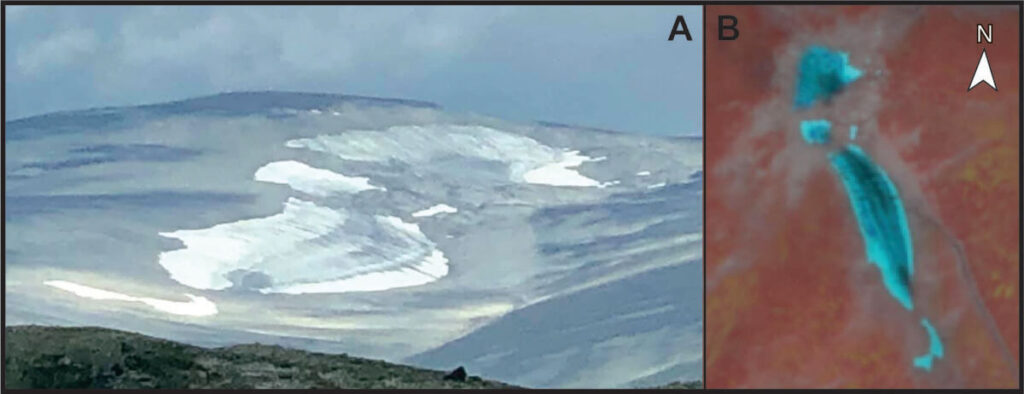

We can also gain intel from long distance ground photography and satellite imagery. When there is little cloud coverage, Sentinel 2 satellite imagery is a valuable tool, albeit with a 10 m resolution. On such photos, we can see snow from the previous winter and exposed old ice, and thus assess the melting situation without having to visit the site.

The decision on which sites to target a given year is made just before the fieldwork starts, based on the most recent information available. At the same time, equipment is checked and packed to make sure everything is ready for the field.

The logistics of basecamp surveys

Getting to the sites means a long uphill hike with heavy backpacks. When available, we use packhorses and sometimes human helpers to carry equipment and food up to the sites. In the past, we have also used helicopters but we have decided to cut back on helicopter use to reduce the carbon footprint of the program.

Due to the extreme environment, we need to prepare for all kinds of weather, including blizzards and freezing temperatures. Our tents are Everest-rated, and they need to be, to be able to withstand the bad weather we experience. On basecamp surveys, each team member normally has his/her own tent, and we also have a common mess tent.

We use inflatable and insulated sleeping mats, allowing us to sleep on rough ground and permafrost. This makes it possible for us to place the camps high, close to the ice. The crew members need to bring winter sleeping bags as freezing temperatures are often encountered during the night. They also need to wear warm and weatherproof clothing.

We need lots of food and drink to keep going during long working hours in cold temperatures. When we have transport available, we bring fresh food. We use the snow as a cooler. When we must walk up to a site on our own, we rely on freeze-dried food, which the team refers to as “inflatable” foods.

We use gas/spirits-cookers for preparing the meals. There is also a heavier multifuel double cooker available, which we use when we have transport help in and out. We normally drink the water available on the site without boiling or purifying it. So far, this has worked out OK. However, recent studies show that ancient microbes and viruses survive inside the ice (read here), so we should perhaps start to boil the water before drinking it. This would require bringing a lot more fuel to the sites.

Survey technique

How we survey the sites depend on what kind of site it is and the available time. On big sites, surveys can cover large areas, and it is important that the work is done systematically. Otherwise, areas may be left un-inspected and finds may be missed. The standard way of doing this is starting at the edge of the ice, and walking on the ground along it, with two meters between the individual surveyors. The person furthest away from the ice places large bamboo sticks with black duct tape flags at regular intervals. They mark the outer perimeter of the survey.

Finds are marked using smaller sticks with a blue tape flag. When we reach the farther end of the survey area, we turn back and use the line of large bamboos sticks as the inner perimeter of the “return” survey. When we reach one of the large bamboo sticks, the innermost surveyor passes the stick along the line and the outermost surveyor places it c. 1 m outside his survey line. In this way, total area coverage is secured even if survey lines are not straight.

Once a few finds are discovered and marked, two members of the survey team separate into a finds collecting team. They photograph the finds, measure their location using a high-precision GPS, and collect and pack the individual artefacts. When we conduct systematic surveys, we usually collect all artefact finds and bones/antlers.

Excavation

We regularly remove stones on a find spot to search for parts of an artefact that may have slipped further down into the scree. This is typically the case with arrowheads. On occasion, part of an artefact is still stuck in the ice. We prefer to let Mother Nature do the excavation work if possible, awaiting the melting of the ice to free the artefact. Ice axes and chainsaws can wreak havoc if not used carefully.

In rare instances, we need to get the artefact freed from the ice immediately. This happened recently at Mount Digervarden, when we discovered a 1300-year-old ski still stuck in the ice. It was late in the field-season and the melting had stopped. We hacked the ice away with an ice axe and poured lukewarm water on the artefact. This freed the grip of the ice and we were able to bring the ski down from the mountain.

Drones

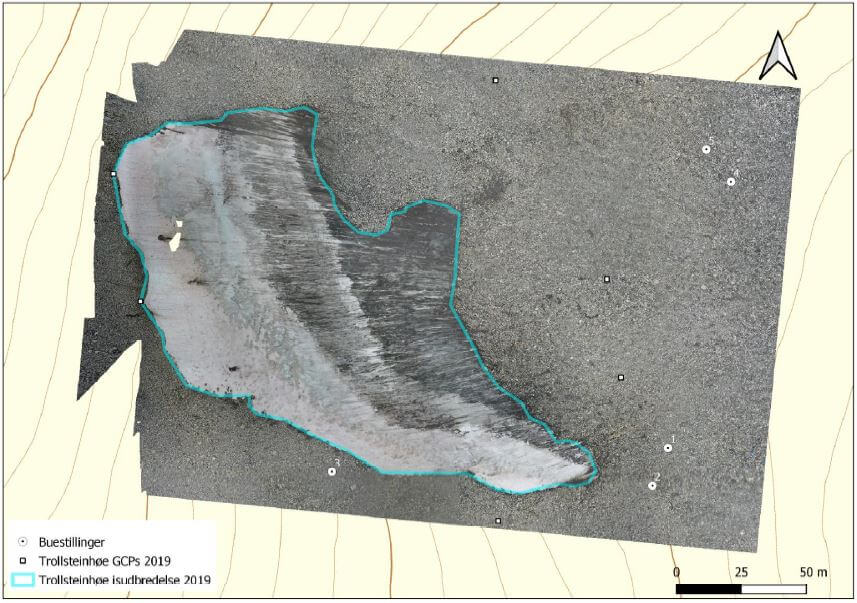

Recently, we have used a drone for aerial mapping of a glacial archaeological site. This worked well, but is especially suited for smaller ice masses, as Norwegian rules only allow flying drones in line-of-sight.

Monitoring

When it is a year of heavy melting, we return to sites that are already surveyed and had their finds collected. In those cases, we only monitor the newly exposed areas, normally in front of the ice. Sometimes, we also inspect the surface of the ice, when black ice (dark old ice) is exposed. If we are lucky, we can catch the artefacts just as they melt out on the ice surface.

Safety

Working at the glacial archaeological sites is not without hazards and we place a lot of emphasis on safety during fieldwork. Generally, we try to avoid potentially dangerous situations. We do not walk on the ice without crampons. We try to be careful in the scree, especially when it is steep. When the weather is bad, we stay in the camp. In 2012, we had two tents collapse on us during heavy winds at the Lendbreen ice patch. Our RedFox tents kept us safe until the wind died down.

Being a glacial archaeologist

As you can see from all the above, glacial archaeology requires a lot more than a quick trip to the ice to collect fantastic finds. We need to find the ice sites first, using a variety of methods and our knowledge of how glacial ice can affect the artefacts. Then we need to conduct exploratory surveys at the chosen ice masses to check for finds. Once we discover a large site with many finds, we need to plan a proper systematic survey, which involves a lot of logistical challenges. Such surveys include a basecamp and longer stays at the ice.

When we get all our ducks in a row, and the site is right, being a glacial archaeologist is one of the best jobs in archaeology. The finds are spectacular, the scenery is wonderful, and you get that good old expedition feeling, which is hard to come by in regular archaeology in the lowlands. Fieldwork at the Lendbreen site is one such example (read here). However, we have also experienced blizzards, evacuations and zero finds, but even such hardships can be rewarding in their own way. They are part of the experience.

You can read more about how we find and document ice sites in our new scientific paper (open access)