The discovery of Ötzi the iceman in 1991 was the first archaeological find from the ice to gain worldwide attention. However, he was by no means the first find from glacial ice. Such finds appeared already in the early 20th century.

Early finds from the ice

An arrow found at an ice patch in Oppdal in Norway in 1914 is the first reported archaeological find from glacial ice. Unsurprisingly, it was a very hot summer that year. The earliest finds are invariably linked to such extra warm summers with a marked ice retreat. Finds also appeared elsewhere: a newspaper clip from British Columbia, Canada from 1925 describes an arrow found on ice in 1924.

Even more finds appeared in Oppdal during the very warm summers of the 1930s. Innlandet County, which borders with Oppdal, also had a few finds then. Things then quietened down until the 1990s, but there were ocacsional finds in the 1970s in Innlandet, like a Viking Age spear recovered from the Lendbreen Ice Patch.

The find explosion

Ötzi the iceman, melted out of the ice in the Tisenjoch pass in the Tyrolean Alps in 1991. He became the starting gun for the second wave of ice finds. Six years later, lots of arrows, atlatl darts and palaeo-zoological material started melting out of the Yukon ice patches. A long-term program was initiated to rescue the Yukon finds.

Pretty soon similar finds, but fewer in number, appeared elsewhere in Western Canada (North-West Territories, British Columbia and Alberta), in Alaska and in the U.S. part of Rocky Mountains. More finds appeared in the Alps as well, especially from the Schnidejoch site in Switzerland.

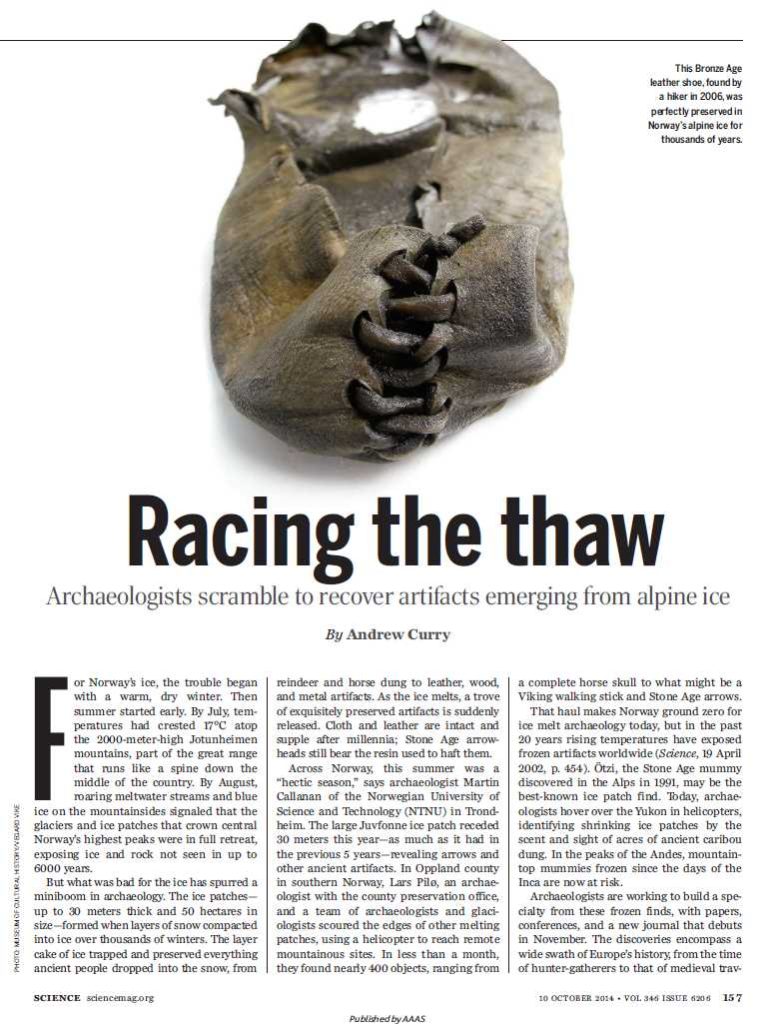

The dramatic melt in Norway in 2006

A dramatic melting episode in Norway in 2006 led to an explosion of finds here. There had been a few finds melting out in 2002-2003, as a forewarning that something was afoot. In 2006, there was a long and hot autumn, which led to very heavy melting. Hundreds of finds melted out of the ice in Innlandet County that year. The high mountains of Innlandet have seen repeated episodes of melting of old ice in 2007, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014, 2018 and 2019. More than 3700 archaeological finds from 65 sites have now been reported in Innlandet County alone. This makes Innlandet the most finds-rich area for glacial archaeology globally with more than half the finds worldwide. Like Yukon, we have a long-term funded program for rescuing the finds from the ice.

Oppdal has also seen melting and many new finds. Recently, finds have also started to appear in other mountain regions in southern Norway.

The nature of the melt

Having worked in the field of glacial archaeology for more than fifteen years, we now understand the mechanisms of melting better. The ice patches, where we discover most of our finds, are clearly on a downward trajectory. This does not mean that they get smaller every year. Their size goes up and down, but the trend is clearly down, just like the Arctic sea ice (more on the nature of ice patches here).

It is the same in other parts of the world. Our Yukon colleagues had a quiet period in the first part of the 2010s, before major melts hit them in 2016, 2018 and 2019. It is clearly an advantage to have a long-term funded program, allowing for the ups and downs in the melting situation. Short-term projects may (and have) hit a quiet period with little or no melting of old ice. Little work can be done with large snowdrifts covering the ice. This makes it difficult to get further funding.

Mongolia became part of the world of ice patch archaeology in 2019. An American-led team made the first discoveries in the Altay Mountains.

The future of glacial archaeology

That was a short history of glacial archaeology, from the small beginnings in the early 20th century to the find explosion from 1997 onwards. What lies ahead? Well, the mountain ice will continue to melt. It is hardly a bold prediction to forecast that more spectacular finds will be made in the regions where fieldwork is already taking place.

There should also be other places where archaeological discoveries are still waiting to be made. Especially in the Himalayas where old caravan routes crossed the ice fields. At the moment, the finds from the Himalayas are limited to missing mountaineers, but that is likely to change.

The prospect of making new discoveries from the retreating ice in the coming years is exiting and sad at the same time. As glacial archaeoogists, there is little we can do to stop global warming and ice melt. Our priority is to record the history of a melting world. The task is to rescue the artefacts, preserve them for the future and try to unlock the stories they can tell about the past. As our recent paper on the lost mountain pass at Lendbreen showed, the story told by the finds is very relevant to the world we are living in today. Climate change was a challenge in the past as well.