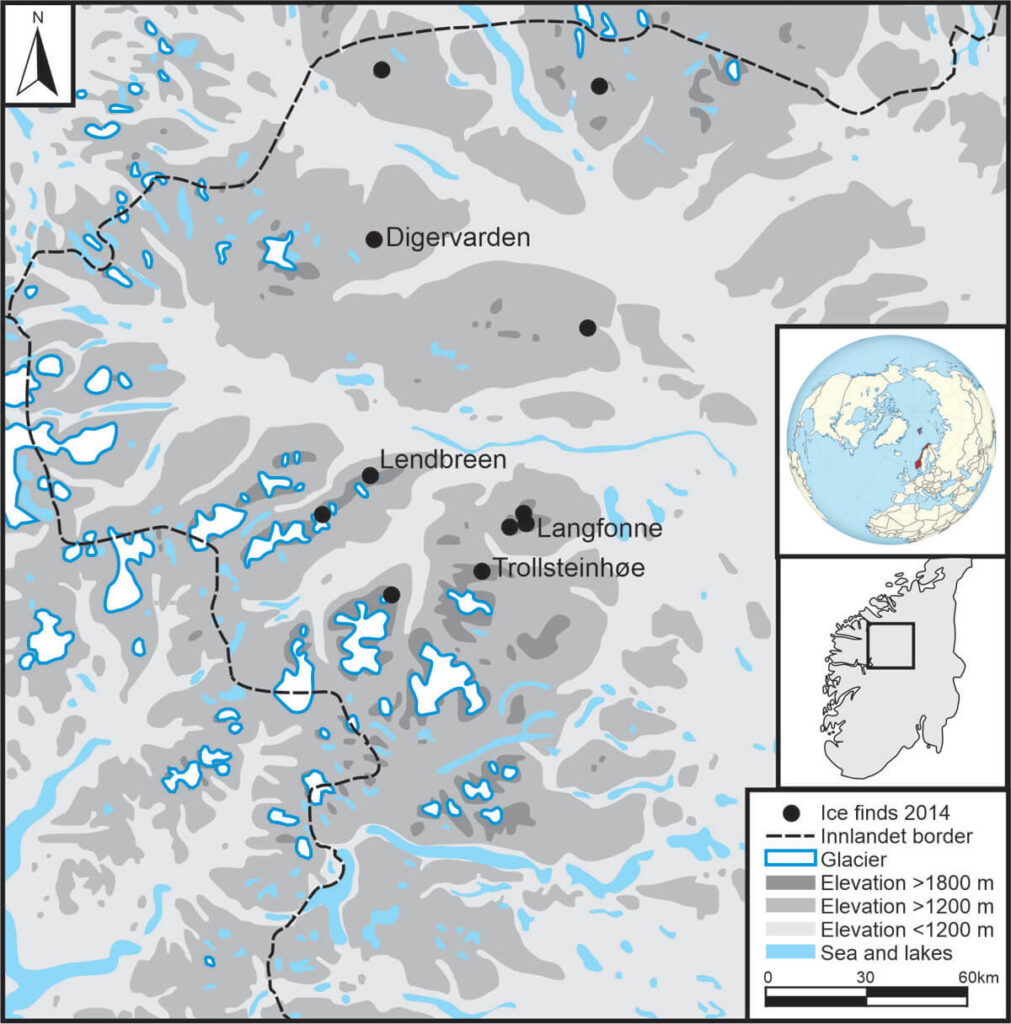

The year 2014 marked a turning point for glacial archaeology in Innlandet. The thick snow cover from 2012 finally gave way, exposing ancient ice that had long been sealed from view. And as that old ice began to melt, artefacts started pouring out — more than we could have imagined.

The season’s highlight was undoubtedly the survey at Langfonne, where we uncovered a record-breaking number of arrows. But we also returned to Lendbreen and Trollsteinhøe, where new finds were waiting. Most exciting of all, 2014 brought the discovery of the first Digervarden ski — an Iron Age object so well preserved, it changed how we understand prehistoric skiing.

There was additional fieldwork, but here we will focus on the highlights that made 2014 a landmark year in glacial archaeology in Innlandet.

The core field team in 2014 consisted of Elling Utvik Wammer, Tessa de Roo, Runar Leifsson, James H. Barrett, and Lars Pilø. Due to the many finds, several additional archaeologists were involved in parts of the fieldwork.

Langfonne Ice Patch: Glacial Archaeology in Innlandet at Its Best

Langfonne is one of the most significant sites for glacial archaeology in Innlandet. Artefacts first began melting out of the Langfonne ice patch in 2006, starting with the remarkable discovery of an Early Bronze Age shoe and a series of arrows. In the following years, a few more arrows were recovered from the site, but systematic surveys were delayed due to a combination of other urgent sites and challenging snow conditions. Finally, in mid-August 2014, we were able to carry out a large-scale systematic survey.

Langfonne is unusual for its southeast-facing orientation—most ice patches in the region face north or northeast. Its exposure to sunlight makes it especially prone to melting.

The results exceeded all our expectations: we found 22 arrows in just one week before snowfall halted the work. Two smaller follow-up surveys in September yielded even more arrows, some lying directly on the ice surface. This was clear evidence that deeper, older layers of ice were now melting.

We could see from the shape of some of the arrows that they were pre-Iron Age. However, we were shocked when later radiocarbon dates revealed that five of them were around 6000 years old!

Read more about the Langfonne site and the finds there in this post.

Lendbreen Ice Patch – 2014 fieldwork highlights

In late August, we were back at Lendbreen ice patch. From a distance, we could already tell that the melt wasn’t as dramatic as at Langfonne, but it was clear that changes were underway. Along the edges of the ice, ancient layers were surfacing — old, dirty ice long hidden from view. That meant one thing: artefacts were likely melting out as well.

At the very top of the ice, near the old trail that led through the pass, a patch of brown-streaked ice had appeared. The unusual colour came from Iron Age and Medieval packhorses—specifically, their dung. This was a well-travelled route in the past, and the ice still carries traces of that traffic.

Mysterious Wooden “Wrench”

One of the most puzzling finds was a small birch object, radiocarbon-dated to the 8th century AD. It resembled a wooden wrench, and although its exact use remains unknown, we suspect it was used to secure loads on packhorses. Two similar items have since melted out at Lendbreen, both dating to the Bronze Age.

The Horse in the Ice

We also found a large horse skull, dated to around 300 years ago — the youngest find from Lendbreen. More bones from the same horse emerged in later years, including, in 2019, a hoof still fitted with an iron horseshoe. A haunting trace of a journey that never finished.

Runes in the Tent

One find only revealed its secret after we had left the ice. It was a broken wooden walking stick, found near the trail. That evening, while sorting and packing in the tent, we noticed something extraordinary: a runic inscription. The runes, along with a radiocarbon date of the wood, placed it in the 11th century AD. As for the message? Likely a name, either “Owned by Ivarr” or possibly “by Joarr.” Short, but deeply personal.

How we discovered the runes.

Trollsteinhøe Ice Patch – 2014 discoveries

With the melt accelerating in 2014, we brought in an extra team from the county council to investigate the Trollsteinhøe ice patch. The effort paid off.

Among the new finds were classic signs of ancient reindeer hunting, scaring sticks, and a beautifully preserved wooden walking stick, 1500 years old according to the radiocarbon date.

A Knife Through Time

The standout discovery from Trollsteinhøe was, without doubt, a stunning Iron Age knife, dating back to the 5th or 6th century AD. What made it so remarkable wasn’t just the blade—it was the whole knife. The birch burl handle had survived intact, still fitted to the iron blade after 1,500 years in the ice.

Before this find, such knives were only known from corroded iron remains. The Trollsteinhøe knife gave us, for the first time, a complete picture of how these tools actually looked and felt in the hands of their Iron Age owners.

The discovery sparked a wave of reconstructions by our followers on social media—bringing Iron Age craftsmanship back to life in the present day.

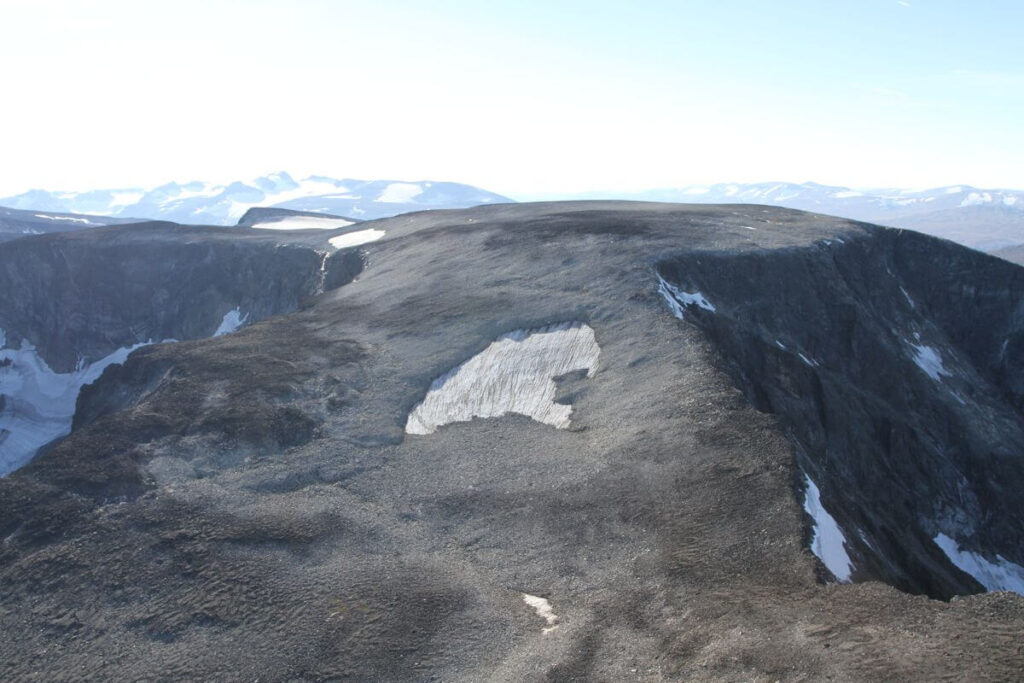

Jackpot at the Digervarden Ice Patch

We had long suspected that Digervarden, the largest ice patch in Reinheimen National Park, could hold ancient treasures. As the largest of only two ice patches in the area, it was a likely summer refuge for reindeer fleeing swarms of botflies. That made it a promising site for ancient finds, but we had no idea just how promising.

To explore the site, we brought in local archaeologist Runar Hole. He barely had time to reach the ice before making his first discovery: an Iron Age arrow. Then came two more arrows — this time from the Bronze Age. And then, the jackpot.

Runar had found something extraordinary: an ancient ski, perfectly preserved in the melting ice. It was clear from the design that the ski had to be at least 1,000 years old. Even better, parts of the original binding were still attached, an incredibly rare survival on prehistoric skis. Radiocarbon dating confirmed its age: 1,300 years old.

You can read more about this discovery and other ancient skis here.

The Wait for the Second Ski

Since skis often come in pairs, we kept a close eye on the Digervarden site in the years that followed. In 2016, we carried out a large systematic survey, hoping the second ski might emerge. But it wasn’t until 2021 that satellite images showed the ice patch had retreated further. We sent Runar back to the findspot—and there it was. Just a few meters from the first: the second ski, even better preserved than the first!

Among the many incredible finds of glacial archaeology in Innlandet, the Digervarden skis stand out. Together, they form the best-preserved pair of prehistoric skis ever found. More on this incredible discovery here.

Media Coverage

Our work in 2014 caught international attention. Science Magazine featured our research in Innlandet in a broader article about glacial archaeology.

Summing up

2014 proved to be one of the most exciting years yet for glacial archaeology in Innlandet. As the old ice emerged from beneath years of snow, we were rewarded with a flood of new discoveries. Langfonne yielded a record number of arrows—including some more than 6,000 years old. At Lendbreen, we found mysterious wooden tools, a horse lost in the ice, and a runic message hidden in a broken walking stick. At Trollsteinhøe, a complete Iron Age knife gave us a rare glimpse into past craftsmanship. And at Digervarden, we uncovered the first of what would become the world’s best-preserved pair of prehistoric skis.

2014 reminded us of both the fragility of these icy archives — and the urgency of documenting them before they are gone forever.