What are glacier archaeologists doing in the winter? Survey and other fieldwork is obviously off the table for quite a few months. Well, we are sitting here in our bunker, following the development in our snow situation room.

No, just kidding, we are not. We use the winter to analyse the finds, write site reports, plan the next field season, answer media enquiries and lots more. And yes, we do follow the development of the snow situation in the mountains, but not in a bunker. More about the snow situation later, but first some words on our more normal archaeological office work.

Report work

All archaeological fieldwork needs to be properly documented and written up in a report. Not doing so, is as close to a deadly sin you can get in archaeology, outside just robbing the sites. So even though we would rather do fieldwork than deskwork, there is no way around it. All available information has to be systematized, site maps prepared, finds catalogued, photos listed og report text written. The interesting part is when the actual writing of report text gets going after all the tedious routine work. This is when the distribution of finds in time and space is analysed, together with the other information about the site.

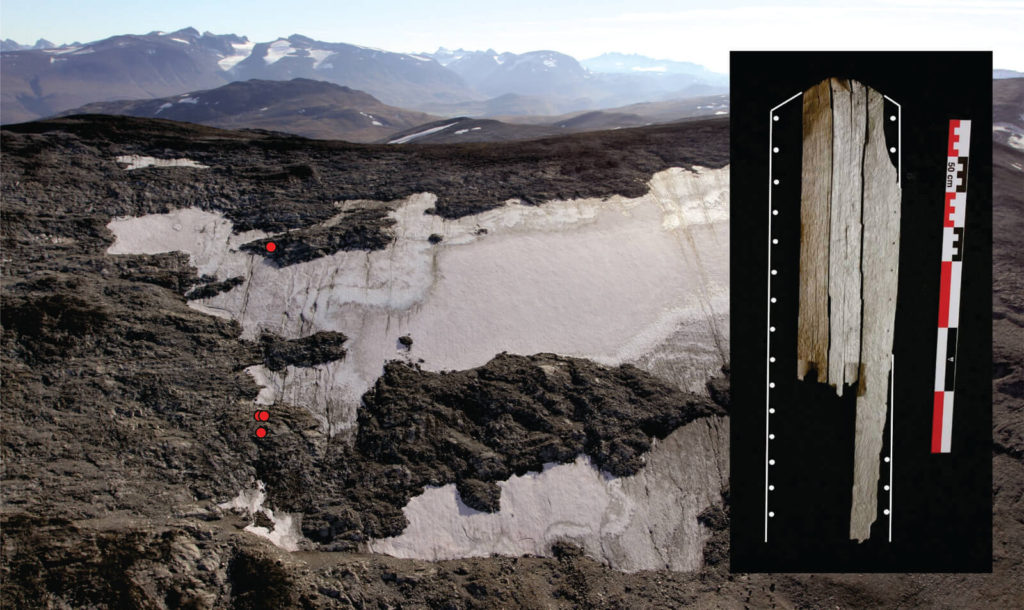

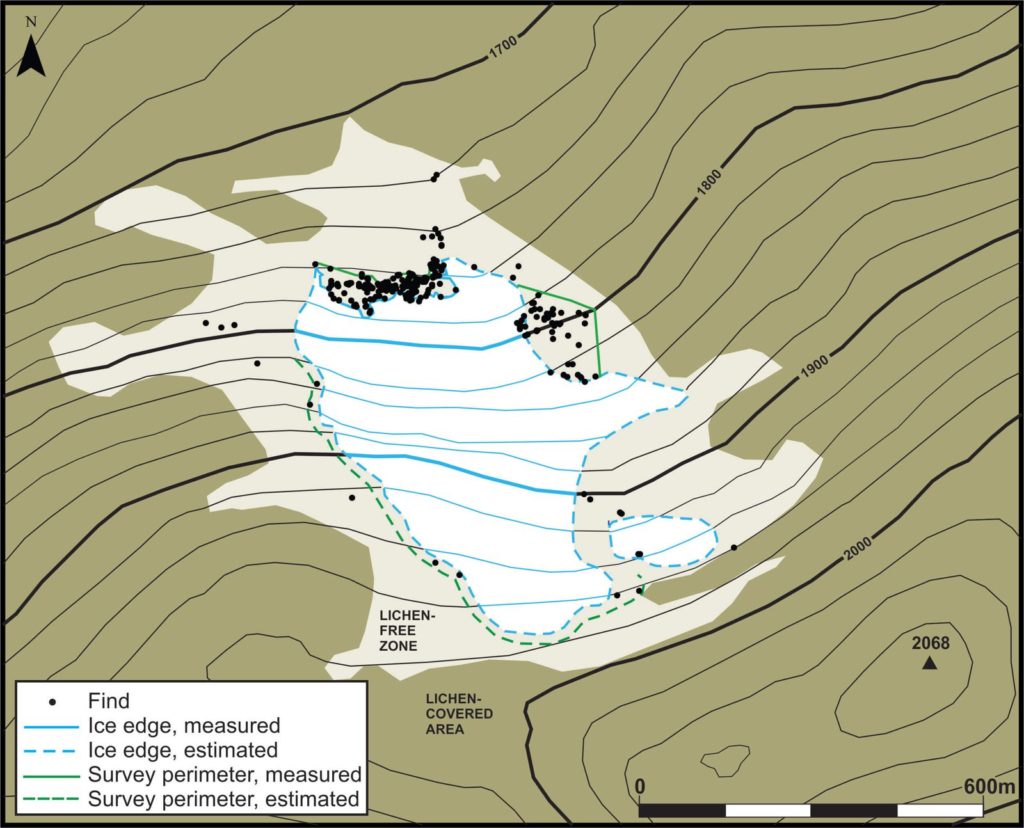

Sometimes the report work really pays off and we get a Eureka moment, making up for the many days staring into a computer screen instead of at beautiful mountain scenery. Let me give you one example. In 2011 we found the glaciated mountain pass site on top of the Lendbreen ice patch. Hundreds of finds were recovered here that year. Among these was a thin wooden plank with small holes along one side. We suspected that it could be part of a ski, but due to its fragmentary state this remained uncertain. In 2012 we recovered more finds further down the slope here. During the cataloguing of the finds at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, it was discovered that two of the wooden finds from 2012 fitted together. And what was even more exiting: they also fitted together with the longer wooden plank with holes. The two new pieces showed a foothold. So, it was a ski, and the small holes along the side showed that it had been lined with fur. In the following years another, smaller part of the ski was recovered. A radiocarbon date put the ski in the Late Bronze Age – c. 600 BC. Not only was this a sensational find for ski historians, but the distribution of the different parts of the same ski along a 250 m long stretch of the slope really opened up our eyes to the crazy nature of our ice sites. It also told us to look far and wide for the parts of the ski still missing.

Media enquiries

From the start of our glacial archaeology rescue work we have had loads of media enquiries (see some of them here). Exciting archaeological discoveries caused by climate change is an irresistible combination for the media. We talk to journalists, provide them with photos and videos for free, supply them with contact information to our colleagues and make sure that the information that comes out in the end is accurate enough. We also get contacted on a regular basis by TV producers or scouts (mostly American or British), who want to include our work in documentaries.

Next field season

Planning for the next field season is an important part of the winter office work. As the report work on the individual sites progresses, we gain a better impression of which sites are in most need of fieldwork. Due to the difficult and changing conditions we normally operate with three main fieldwork plans. Plan A is for a normal snow situation; plan B is for an excess snow situation and plan C is for a melt situation. We also have a separate emergency plan if the melting gets really bad. I will get back to how these different plans look for the coming year in another blog post.

In late July, we decide on which plan to choose depending on the snow conditions, and that brings us back to the snow situation room mentioned at the start of this post.

Snow situation

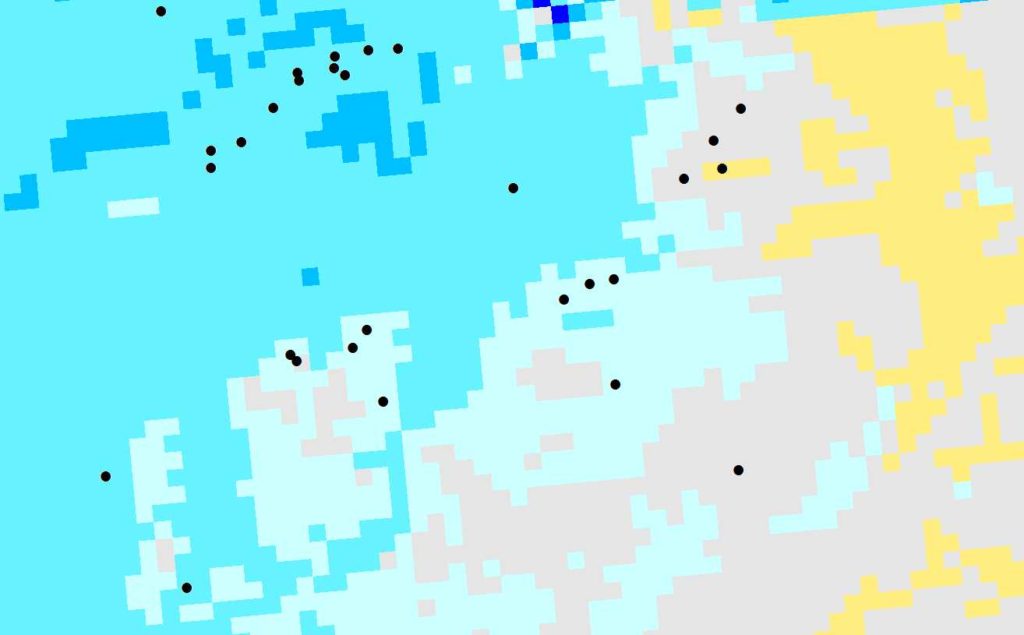

There are different ways we can collect information on the development of the snow situation during the winter. The Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate has an excellent website, which shows the current amount of snow, broken down to 1×1 km2 squares. The numbers are partly based on actual snow depth measurements and partly on modelling. The site even provides 10-day forecasts and comparisons to the normal for the years 1981-2010. This gives us updated information on the general amount of snow in the high mountains, and also provides information on when the melting starts and how fast it develops. This general information will help us decide whether we are in a plan A, B or C situation.

However, the general information is not specific enough for the individual ice sites. Most of the snow accumulating on the glaciers and ice patches is brought there by wind drift during snow storms. Even if there has been little precipitation during the winter, one large storm can deposit lots of snow on a site (read about this here). For this reason, we also need to collect ground intelligence. This can be done by either observing from a distance with binoculars, actually visiting the sites on ski in late winter or on foot in the summer or using webcams on the very few sites, where they are available.

In the end, it is the summer melt that decides how the field season will pan out, more than the actual amount of snow on the sites at the end of the winter.

So yes, there is a lot to do for glacier archaeologists in the winter as well.