Finally, the long wait was over and we were so ready for fieldwork!

We had chosen two large sites for the main fieldwork in 2017 – the Lauvhøe and Storfonne ice patches, both situated in the northeastern part of the Jotunheimen Mountains. More details on why these two particular sites were chosen can be found here.

Both sites had only seen short visits prior to this field-season. This had resulted in a number of artifact recoveries, especially arrows, found close to the melting ice. However, we knew that there were other finds on these sites, and that they were lying on the surface, exposed to the elements. The main job would be to rescue these artefacts. To achieve this, we planned to conduct a systematic and thorough survey of the lichen-free zone (where the ice has melted recently) surrounding the ice on both sites.

For general information on how glacier archaeology fieldwork is conducted, read here.

The Lauvhøe ice patch

The Lauvhøe ice patch was up first. The earliest finds from this site were reported in 2007: three arrows, dating to the Iron Age and the medieval period. Even with these remarkable finds, the site had to wait ten years for a proper systematic survey. This may sound harsh, but with the short time window available for surveys each year, other sites with more and older finds had to be surveyed first. Lauvhøe’s turn had finally come this year.

The site is situated a three-hour hike and 600 height-meters from the nearest road. Due to the relatively easy access, we decided to backpack in. Local high school students helped carry our equipment.

Video: First morning in the basecamp (1500 m) at Mount Lauvhøe.

We arrived at the camp site at around 8 p.m. The campsite had easy access to water and a rather level ground, but it was situated in a pass, leading to a lot of wind funneling through the area. Just as well that we have Everest-rated tents. Finally, around 10 p.m. we could turn in for the night.

The Lauvhøe ice patch consists of a large, permanent ice patch and a number of smaller, non-permanent snow patches. The survey was focused on the lichen-free area surrounding the main ice patch. We also managed to survey most of the areas surrounding the smaller snow patches. As a result, we will not have to return to the site again before we see heavy melting, exposing new non-surveyed ground here.

Video: Axel, one of our volunteers, with a 1500-year-old arrow, that he found during his first day in the field.

Five Iron Age and Viking Age/early medieval arrows were found during the survey in front of the main ice patch. Remarkably, each arrowshaft had an iron arrowhead associated with them, as was also the case with the arrows recovered here in 2007. On other sites, we rarely find arrowheads associated with arrowshafts in front of the ice. We believe the arrowheads were lost, when the arrows were washed down the surface of the ice by meltwater. Well, not so at Lauvhøe. It only goes to show that each ice patch site has its individual traits.

It is also interesting to note that this site has so far not yielded Stone Age or Bronze Age Arrows, contrary to ice patch sites a bit further east. This is probably because the melt at Lauvhøe has not reached the really old ice yet.

Video: Iron arrowhead from the Viking Age or Early Medieval Period.

In addition, we found a large number of quite thick, but poorly preserved sticks in the northernmost area at Lauvhøe, where the non-permanent snow patches are. A similar stick, found during the 2007 survey, was dated to the 11th century AD. These sticks are probably not scaring sticks, but part of some sort of fence. There are substantial remains of hunting blinds and other reindeer hunting installations near the ice patch. Maybe the fence is connected to these installations in some way.

After a week at Lauvhøe in windy and cold conditions, we hiked down to the cars. This time we did not have help from local sherpas. However, we had eaten a lot of the weight they had carried up to the camp! Still, lots of stuff needed to be brought down, and two members of the crew ended up carrying 40 kg+ packs.

The Storfonne ice patch

After resting two days in the lowlands, we headed up to the Storfonne site. This site had previously yielded seven arrows, two of these dating back to the Bronze Age. A number of scaring sticks had also been observed. Unfortunately, the site has been looted and many of the scaring sticks are now missing. Due to the looting, we were worried that there might not be many finds left on the site. It turned out that these worries were completely unfounded!

Again, we got help from local students and friends in carrying up food and equipment.

In contrast to our normal routines, we did not inspect the planned site for the basecamp beforehand, but relied on local information. As we approached the location of the campsite, the valley got narrower and steeper and the valley floor turned into scree. We started to have our doubts about the suitability of the area for a large basecamp site. However, just as we neared the end of the valley, we found the promised spot: A beautiful and secluded campsite with level ground and a brook nearby. There were even small snow patches, where we could keep our fresh food cool. Heaven!

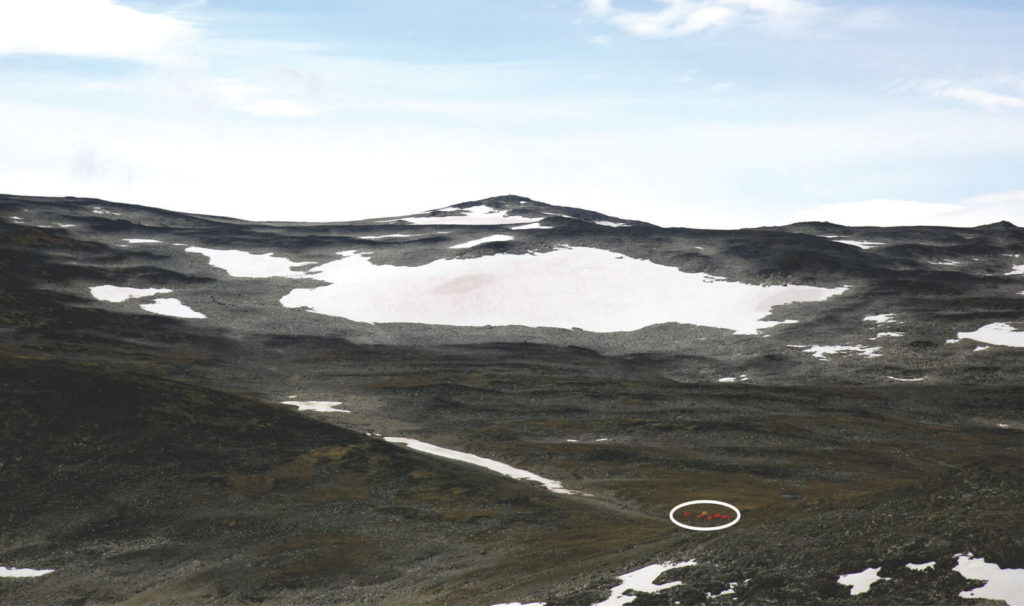

There was dense fog in the valley the first morning. For safety, we decided to take a longer approach route to the ice patch through a scree-filled slope on the east side of the valley, instead of scrambling straight up a shorter, but steeper route. Before using the steeper route, we would have to mark a safe path here (which we did at the end of the day). Using our GPS, we were able to navigate a route through the scree in the dense fog. When we got close to the ice patch, the fog suddenly lifted and we got a magnificent first view of the site.

We established a small camp at the site, and most of the crew got straight on with the surveying in front of the ice patch. Two members of the team did a tour of the ice patch to check where areas were available for survey. It turned out that only the large lichen-free zone in front of the lower edge of the ice could be surveyed. It quickly became clear that there were still many artefacts left in the scree here.

We recovered a remarkable c. 110 scaring sticks during the week-long survey at Storfonne. Scaring sticks were used for controlling the movement of the wild reindeer during hunting (read more about scaring sticks here).

In addition, we found five arrowshafts, all without their associated arrowheads. All five were found in front of and near the lower ice edge. The arrowshafts here thus showed the normal situation (in contrast to Lauvhøe), having lost their arrowheads as they were washed down the surface of the ice. Two of the arrowshafts appear to be of a Bronze Age type, i.e. they are c. 3000 years old.

Video: The excavation of a c. 1600-year-old knife at the Storfonne ice patch.

The most interesting single find was a small knife from the Iron Age, found by one of our volunteers. When it was discovered, only the handle was visible in the scree. Subsequent removal of the stones revealed that the blade was also intact (watch the video). This knife is such a nice and cool artifact, left behind by a reindeer hunter c. 1600 years ago.

We had great help from volunteers at Storfonne. Rachel and Allison participated in the survey, and joined our ice scientist in taking ice samples at a neighboring ice patch (including shoveling away 2 meters of snow!). Kjetil and Ronny, two local metal-detectorists, searched through a section of our survey area to try to find iron arrowheads. No such luck, but the conditions for use of metal-detectors were good. It is just that there is so much ground to cover and so few arrowheads to find.

The survey at Storfonne started with several days of very nice weather and little wind. That was a nice change from the cold and windy conditions at Lauvhøe. However, the weather deteriorated towards the end of our stay at Storfonne. The wind picked up, and the temperature dropped. We had to break off fieldwork at the ice patch when the wind reached gale strength, but we managed to complete the survey in front of the ice first.

The nice, calm weather had made us complacent. We had not fastened the tent plugs for the mess tent securely enough. When the wind picked up, strong gusts of wind came down the steep slope from the site and hit our campsite. One of these gusts picked up the large mess tent and threw it 50 m down the valley. Incredibly, it only sustained light damage. It would probably be fair to say that our pride suffered more than the tent. There is no room for complacency in the high mountains. You simply have to be prepared for quick changes in the weather.

With the wind howling up at the site, we used the last field day down in the valley. We surveyed for ancient monuments and took ice samples. Old, dirty and layered ice had appeared at the bottom of an ice patch, north of the main ice patch at Storfonne. This kind of ice has been dated to the Stone Age and Bronze Age elsewhere. We took three samples here, which will be dated in the fall.

The survey at Storfonne was over.

The Sword

After coming down from Storfonne, we hoped for further melting. This would potentially have made it possible for us to continue fieldwork throughout the autumn, monitoring freshly exposed areas on previously surveyed sites. It was not to be. The autumn weather turned cold. It appeared that the field-season was over. Not quite! The greatest find of the field-season was still waiting for us – a Viking sword!

You can read about the sword find here. News about this remarkable find traveled around the world (e.g. Fox News, Russia Today and Washington Post).

Summing up the 2017 field-season

The field-season this year saw limited melting. This gave us the opportunity to target two sites, which were in dire need of surveying, because they were known to contain material melted out in previous years, lying exposed to the elements. We managed to conduct large, systematic surveys at both sites, recovering more than 150 artifacts of mostly organic materials. These two sites will now be moved from the urgency list to the watch list. The watch list contains sites to visit next time we have a big melt. Then we can just survey along the melting ice, as the artifacts in the previously exposed areas have now all been collected.

We started doing glacial archaeological fieldwork in 2006. In the beginning we kept finding new sites, most in desperate need of fieldwork. The urgency site list grew longer and longer. In the last years we have been able to transfer a number of these sites on to the watch list after completing extensive surveys on them. This is satisfying, but should not make us complacent. We have large areas with potential sites, which have not yet seen their first survey. We also need to be prepared for the next big melt.

Winter snow is falling in the high mountains now and the field-season is definitely over. The ice archaeology enters a new phase – reporting and analyzing the finds.

What will the 2018 field-season be like? We will know more by the end of winter in April next year. By this time, we should also know if we can take volunteers again in 2018. They were certainly a great help this year – thanks to Axel, Allison, Rachel, Kjetil and Ronny.