The ice in the high mountains is melting due to climate change. Archaeological finds, mostly from reindeer hunting and mountain travel, are melting out of the glacial ice in Scandinavia, the Alps and North America. The artefacts are remarkably well preserved. The ice has acted like a time machine, preserving the finds through millenia like a giant prehistoric deep-freezer. This is a new and fantastic archaeological record of past human activity in the some of the most remote and forbidding landscapes.

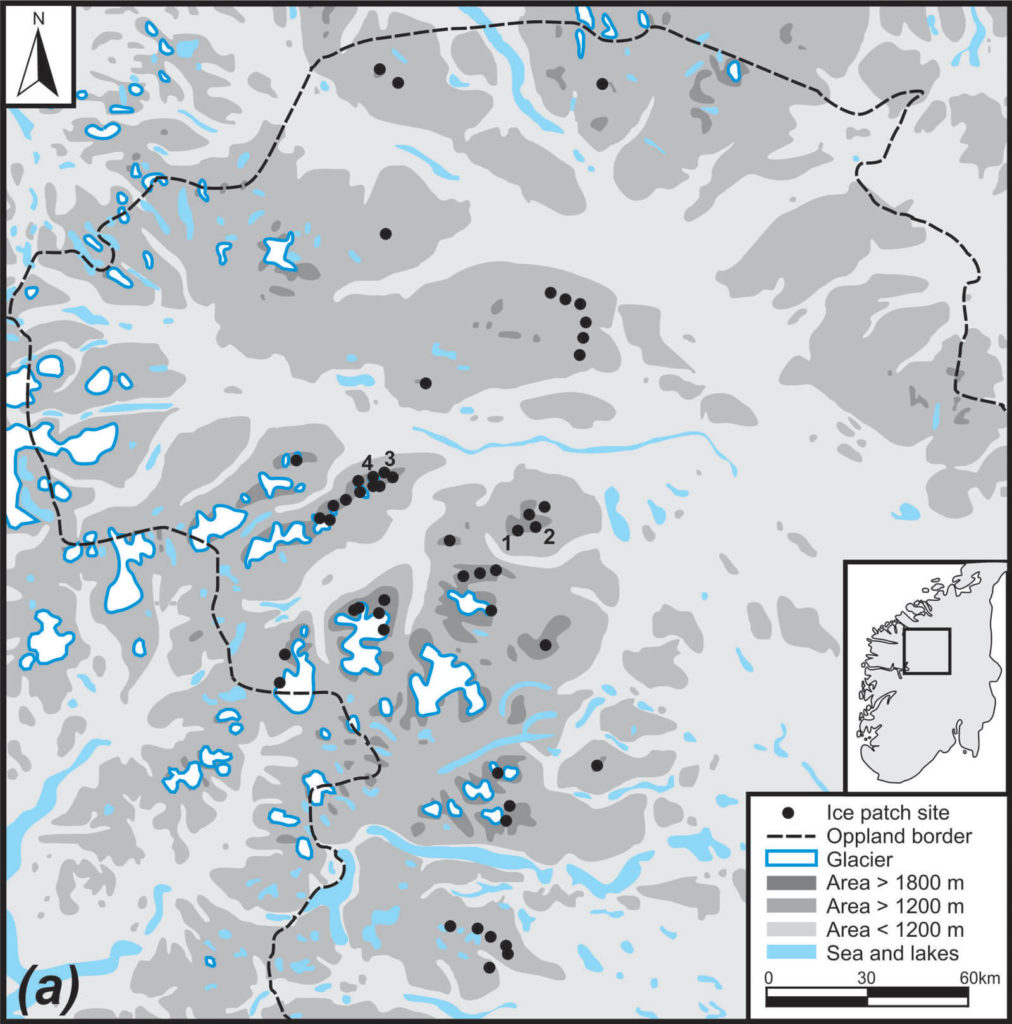

For more than ten years, we have conducted systematic archaeological fieldwork in the high mountains of Oppland County, Norway. We try to find and rescue these artefacts, as the ice continues to melt back. We have now recovered more than 2000 artefacts from 51 ice patches and glaciers. Some of the finds date back to 4000 BC. Among the finds are c. 180 arrows, Iron Age and Bronze Age clothing items and remains of skis, sleds and packhorses.

Many of the finds are rare or unique. The only way to date them is using radiocarbon. Our number of radiocarbon dates has been steadily rising over the years, finally exceeding more than 150 dates. It gradually became visible to us that the finds did not spread out evenly over time. Some periods had many finds, while others had few or none. The large number of radiocarbon dates makes it clear, that this chronological patterning is not by chance. What could have caused this chronological patterning – human activity and/or past climate change?

A international research team from Oppland County Council and the universities in Oslo, Trondheim, Bergen, Oxford and Cambridge set out to solve this puzzle. The result of this effort has now been published in Royal Society Open Science, a journal at the forefront of international open-access publishing, especially of interdisciplinary science.

The paper is available here.

The chronological pattern

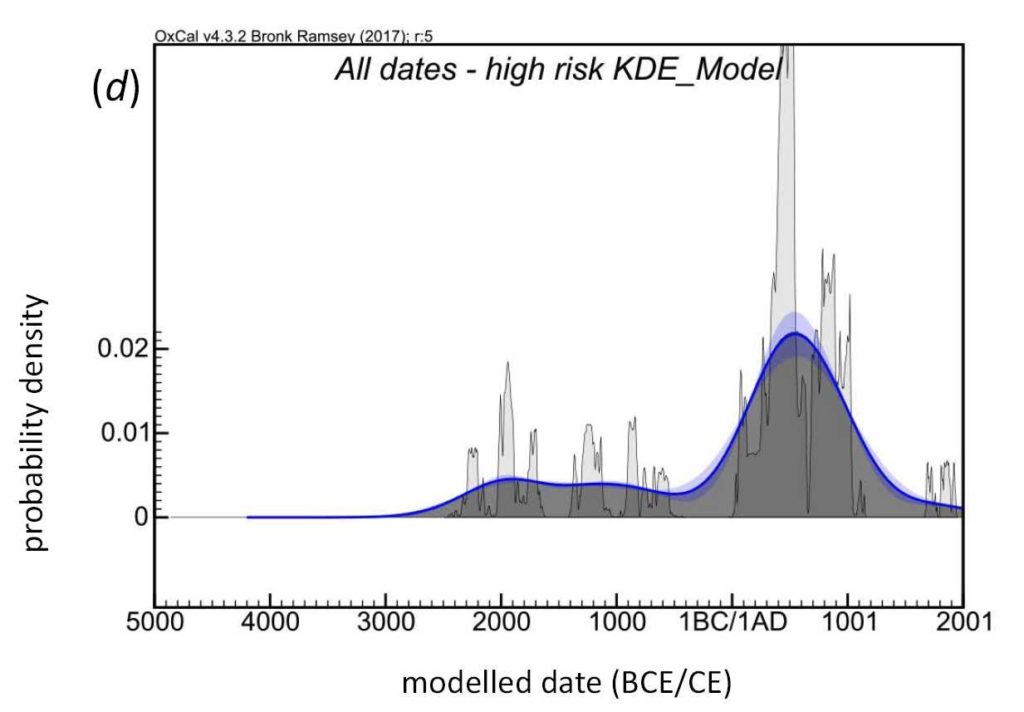

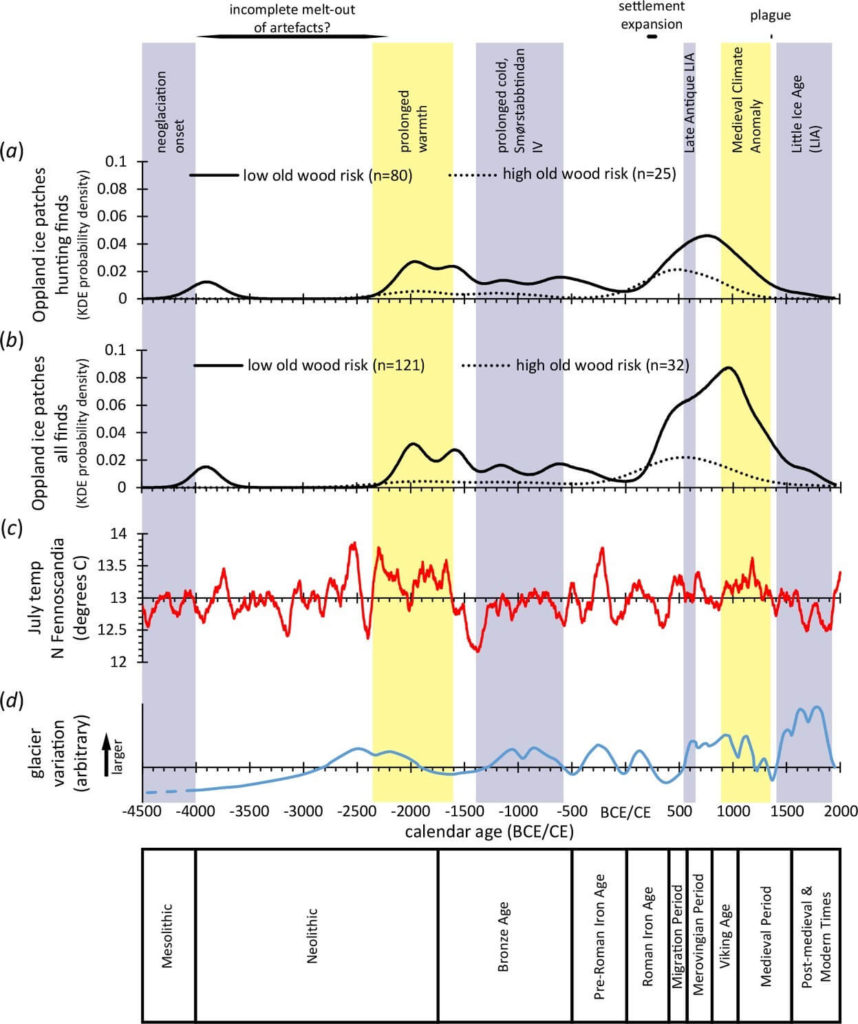

Before we describe the results, a few words are needed on summed radiocarbon plots, as this is fundamental to our paper. Using a large number of radiocarbon dates to provide a time-series of human activity goes back 30 years in archaeology. The increasing number of radiocarbon dates and the arrival of easy-to-use radiocarbon calibration programs (such as Oxcal) has made this type of chronological plot a basic technique in archaeology. As most methods, this method also suffers from weaknesses. In this case it is mainly connected to peaks and troughs in the radiocarbon calibration curve (read more here). Co-author Christopher Bronk Ramsey, who developed the Oxcal calibration program in 1994, has now developed a new statistical method, which eliminates this calibration noise. This new approach, called KDE – short for kernel density estimation, is used for the first time in our paper.

Before using the KDE-model on our radiocarbon dates, we had to take the individual sample materials into account. Some sample types, especially certain wood-species, may be long-lived. This provides a risk of an old wood effect, in which the radiocarbon dates are earlier than the time when the artefacts were lost. We divided the samples into low-risk and high risk groups, and analyzed them separately. The finds deriving from hunting were also analyzed separately.

After doing a KDE-model based plot of our radiocarbon dates, four major findings became visible:

- There are no artefact recoveries from 3800-2200 BC

- The activity increased markedly from the third century AD onwards

- The curve rises through the Late Antique Little Ice Age (AD 536 – c. AD 660), a surprising trend

- After peaking in the eighth, ninth and tenth century AD, the number of dates decrease rapidly, even before the mid-14th century plague

What could be the cause of this?

The Chronological Gap in the Stone Age

The earliest dates are from ca. 4000 BC. This is not long after ice started coming back in the high mountains following the massive melt during the holocene warm period. Before this new glaciation, there was probably very little ice in the high mountains of Oppland to preserve the artefacts.

There is a time gap without finds between 3800-2200 BC. Finds from this period are known from ice patches in a neighboring county, though not numerous. We believe that the finds from this period may still be inside the ice at high altitude (above 1900 m). They may have melted out previously and been lost at lower altitudes (below 1900 m).

As the ice continues to melt, the melt will reach Stone Age levels on more sites. It may well be that this chronological hole will be filled in. It is also possible that the finds may get older than 4000 BC as the melting reaches the earliest ice.

The increase in activity from the third century AD onwards

The chronological plot of the radiocarbon dates shows a marked increase in activity from the third century AD onwards. This fits well with what we know about human activity in the valleys surrounding the high mountains. This is a time of agricultural expansion and of increased economic activity. The increased number of finds from the ice mirrors this.

The Late Antique Little Ice Age

The Late Antique Little Ice Age (AD 536 – c. AD 660) was a cold period, following two large volcanic eruptions. It is commonly believed that this was a time when harvests failed and populations dropped. This could certainly have been the case in the areas near the high mountains in Oppland, which are already at the limits of where agriculture is possible. Remarkably, the number of finds from the ice continues to rise through the Late Antique Little Ice Age. If there was a downturn, it was so short that it is not visible in our data.

Do we have to reconsider the impact of the Late Antique Little Ice Age? Maybe, but this finding could also have another explanation: If agriculture failed due to low temperatures, perhaps the importance of hunting rose. Farmers in valleys surrounding the high mountains of Oppland have always relied on a mixed economy of agriculture and hunting. Adapting to the lower yields from agriculture by increasing the intensity of hunting would have been an obvious choice. This is the same kind of approach taken by the Old Norse settlers in Greenland. When the climate worsened and agriculture became difficult, the settlers increased the hunting of seals.

The recovery of a small blunt arrow, radiocarbon-dated to Late Antique Little Ice Age, is a testimony to the importance of hunting during this period. Due to its small size, it is very likely to be a toy arrow. From a young age, children had to practice and master the art of bow-and-arrow. It was essential for survival, especially during harsh climatic conditions. We found the toy arrow in the glaciated mountain pass at Lendbreen, one of our key sites.

The decreasing number of finds in the medieval period (from the 11th century onwards)

The high number of dates in the eighth to tenth centuries AD probably reflect the increased population and trade in this period. This is a time when the process of urbanization created a market for reindeer pelts and antlers outside the region.

However, the number of radiocarbon-dates starts to wane already in the 11th century AD, well before the the plague in 1349-50 and the onset of the Little Ice Age (from AD 1400 onwards). This may be caused by the replacement of bow-and-arrow hunting for reindeer with mass-harvesting techniques at this time. These included funnel-shaped trapping systems and large pitfall trapping systems. This type of intensive hunting methods reduced the number of wild reindeer quite dramatically, as shown by a recent genetic study.

After the plague in 1349-50, trade and markets suffered, and marginal farms were abandoned. With few reindeer to hunt, human activity in the high mountains slumped. Even after the reindeer population recovered, the introduction of firearms reduced the likelihood of ice patch losses.

Conclusion

The chronological patterning of the finds from the ice is caused by at least four factors – the size of the reindeer population, the level of high altitude human activity, preservation issues and climate history.

Periods with few artefact recoveries may reflect low hunting activity, but can also be a result of preservation issues. Counter-intuitively, a rising number of finds may not necessarily reflect a rising population and increased economic activity. It can also result from a population intensifying its high altitude hunting during periods of low agricultural yields.

Is it possible to get a better understanding of whether reindeer, humans, preservation or climate is the main driver of the chronological patterning in certain periods? Yes, there is one very interesting possibility linked to the paleo-environmental material, which we collect on the sites together with the artefacts. Our next step will be to start dating more of this natural background material. What kind of chronological patterns will this material show? If we find reindeer bones from periods with no artefacts, this would probably rule out preservation issues as the cause of the lack of artefacts. On the other hand, if bones and artefacts are both missing, preservation issues may be at play (or too much hunting).

The first reindeer samples have just been submitted to a radiocarbon laboratory. The results should be back in a couple of weeks.

List of authors

Lars Pilø, Department of Cultural Heritage, Oppland County Council

Espen Finstad, Department of Cultural Heritage, Oppland County Council

Christopher Bronk Ramsey, School of Archaeology, University of Oxford

Julian Robert Post Martinsen, Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo

Atle Nesje, Department of Earth Science, University of Bergen

Brit Solli, Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo

Vivian Wangen, Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo

James H. Barrett, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge