One member of the Secrets of the Ice team is not a professional archaeologist. Reidar Marstein is a hobby archaeologist from Lom. Why is he a core member of the team? Well, there are a number of reasons for that, but the main reason is that without him, glacier archaeology here in Innlandet would have looked very different.

In the early 2000’s, Reidar noticed that the ice patches in the northeastern part of the Jotunheimen Mountains were getting smaller. He thought there was a chance that artefacts could emerge from the melting ice. Reidar explains what happened next:

“2006 was a special year for ice patches and glaciers in our high mountains. The summer was warm, and autumn continued with high temperatures into October. We had never witnessed a melt like that. The ice patches and glaciers were smaller than we had ever seen before.

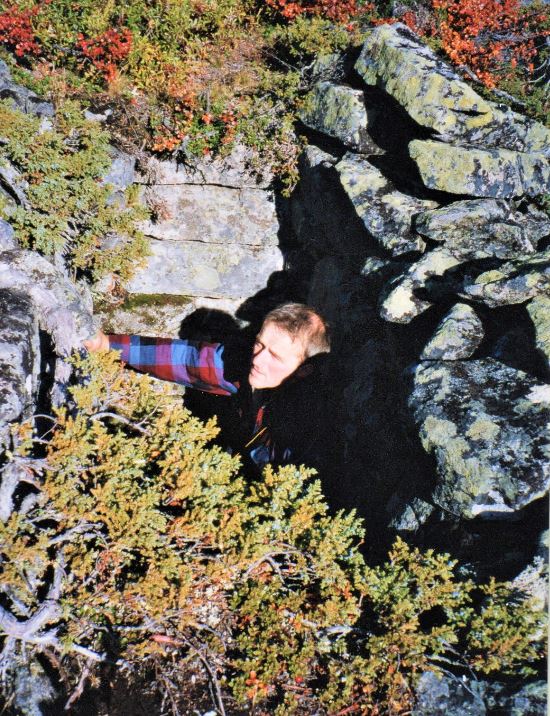

I hiked up to the ice patches every week this autumn. It was my visit on September 17 that became the greatest adventure. I started early in the morning and reached the Langfonne ice patch around 9 am. It was unbelievable how much the ice patch had melted just during the last week. With great excitement, I started my survey around the ice. It had to have been a long time since the last human had set foot here.

After a while, a hunting blind appeared. About 25 metres above the hunting blind, I noticed something lying on the ground. I got my camera and GPS ready, as I had to note the location of the find and take a picture of it. After lifting the object with great care and gently removing some glacial silt, I realised that I was holding a shoe in my hand. Not a regular shoe, but a shoe that had to be incredibly old. I felt confident that it was a reindeer hunter with bow-and-arrow, who had once used it. It was a strange feeling standing at the edge of the ice holding the ancient shoe …

It was clear to me that I was holding a treasure from the past in my hand. The shoe had to be treated with great care. I wrapped it in plastic and paper and put it into a plastic box.

Back home, I put the shoe in the freezer. The next day, I called county archaeologist Espen Finstad, who visited me and collected the find. The shoe has since been radiocarbon-dated to be c. 3400 years old, i.e. from the Early Bronze Age.“

The discovery of the 3400-year-old shoe became the starting gun for glacial archaeology in Innlandet County. The same autumn, many other finds melted out as well, but the shoe was the oldest and most interesting find. More than anything else, it made us realise that something both exciting and disturbing was happening in the high mountains.

How Reidar Became a Mountain Man

Reidar’s discovery of the shoe and other ice artefacts was not a chance find, but the result of a life-long pursuit of the past. How did Reidar become a mountain man with such a great passion for the archaeology and history of his local mountains? That is a fascinating story and it takes us back to very different times…

Reidar Marstein was born and raised on a small farm in the municipality of Lom, in the heart of the Innlandet mountains. He had five siblings. Together with his brother Jan, who was five years older than him, he was often on hikes in the forests and mountains surrounding the farm. They trapped squirrels and stoats, the furs of which were quite valuable.

“I have a strong recollection of the first trip to the Finndalen Valley. I was six or seven years old, and my brother Jan, who was 12 or 13, had taken me along. He was already an experienced trapper. We had not had stoat traps in Finndalen before. We needed to find slabs of stones for the traps, and place them in suitable spots in the ruins of the old summer farm there. Everything had to be ready for the winter trapping season. This was in late autumn, it was freezing, and the ice had started building along the banks of the river. We had to get across to reach the ruins.

We walked along the river until we found a spot where crossing was possible. Jan walked onto the ice, jumped and reached the other side safely. I hesitated when I looked at the jump I had to make – it appeared infinite to me. In the end, I jumped, and of course, I ended up in the river. When I got onto the other shore, I was dripping and my shoes were full of water. My brother gave me his mittens and I used them instead of my wet socks. That worked well and we were able to continue our work setting up the traps.

To give you an idea of the trip that Reidar and his brother went on – it was 8 km as the crow flies, including a 600 height-metre climb across a mountain, and it was freezing. Those were different times.

In the summertime, they went fishing in the mountains. The fish were small, but plentiful. The boys often proudly carried a heavy load home. They sometimes slept by the lakes, just using a bed of reindeer mosses and a paper bag for cover.

“I cannot remember that our parents were negative to us going to the mountains. They surely gave us advice, they gave us responsibility, and we accepted that responsibility. The wife on the neighbouring farm on the other hand gave us many warnings. However, when we got home, we gave her fish, and then everything was OK.”

Reidar and his siblings had to help out on the farm. From the age of eleven, he worked on other farms in Lom during the summer. Working hours were from seven in the morning to late evening. He was paid 5 kroner a day (c. 50 US cents).

The Lure of the mountains

The mountains were a magnet for the boys. They started finding ancient pitfall traps, which the boys found very interesting. It became an adventure to search for pitfall traps, house ruins and other ancient monuments from people who had lived there long ago.

Reidar started visiting other mountains:

“I often hiked by myself, as it allowed me to go where I wanted. I found pitfall traps, sometimes in large systems, and was impressed by all the work put into building these structures. For me is was not just seeing these systems, but just as much sitting down and trying to imagine how they had worked.

I often talked to people who I knew were spending time in the mountains. They told me about pitfall traps and hunting blinds they had seen in certain areas. I then visited these areas, and normally it turned out that there were more pitfall traps and hunting blinds there than people knew.

I heard about people who had found arrowheads in the mountains, and that made me envious. What an experience it would be to discover an arrowhead! It became a dream that just grew stronger and stronger.“

The Jotunheimen Mountains

In 1986, Reidar got a job helping a historian collect evidence of hunting and trapping in his home mountains, a work that lasted two years. He found it very rewarding. After completing it, Reidar started spending more and more time in the Jotunheimen Mountains, especially the Smådalen and Veodalen Valleys. Together with his friend Jan Stokstad, a local reindeer shepherd, he started surveying the ancient monuments in Jotunheimen. This was a great effort, resulting in the mapping of thousands of monuments. All these monuments have now been entered into the national database of ancient monuments. The work also resulted in a book on the history of the Jotunheimen Mountains, co-written with Espen Finstad and Lars Pilø from Secrets of the Ice, Arne Brimi and with Jan Stokstad’s beautiful photos (published 2011).

In addition to discovering many pitfall traps and hunting blinds, Reidar made a remarkable discovery of a site with numerous house ruins in Smådalen. Espen Finstad went to the site with Reidar. Radiocarbon samples were taken and showed that the ruins dated to AD 700-1000.

The first finds from the ice

In the early 1990s, Reidar was on his way home from a fishing trip in the Smådalen Valley, when he decided to take a shortcut over the Kvitingskjølen range (2064 metres above sea level). He had been skiing in these mountains in the wintertime, but had never been there in the summer. As he approached the pass at 2000 metres, he discovered a long stone-built wall leading to an ice patch. There were also many hunting blinds. Reidar had read about arrows that had been found in ice patches in the neighboring county. He imagined that there was a chance of discovering similar finds here. He returned every autumn to check for finds. As we found out later, the 1990s were a period of large ice patches. Thus, Reidar came back empty-handed every time, but he did not give up. Then in 2002:

“When I arrived at the ice patch that autumn, it had melted more than I had ever seen before. My hopes were rising. And there it was: A scaring stick with its flag, lying in front of the ice. It was a great moment for me.”

Reidar delivered the scaring stick to the county archaeologists. It was radiocarbon-dated to be c. 1300 years old. In the following years, Reidar continued surveying the ice patches in the Kvitingskjølen range, and discovered even more ice finds, including arrows. Then in 2006, he found the Bronze Age shoe and everything changed.

Reidar and Secrets of the Ice

The melt was particularly bad in 2006. Artefacts melted out of a number of ice patches in different parts of the high mountains in Innlandet. It became clear to us that we would have to develop an archaeological program to rescue the finds. This program would eventually develop into Secrets of the Ice.

Reidar became a natural part of the program from the beginning. He has been with us on all our major sites. Reidar does reconnaissance work to check for new sites and evaluate the melting status of known sites. He hikes up to the ice to collect artefacts that have been reported by mountain hikers. In addition, he handles some of our practical issues through his local network. Not least, Reidar is a vital discussion partner when exploring the local history, which provides a background for past use of the mountains. All of this is of course invaluable to us, but his greatest contribution is himself. Reidar is a kind and compassionate person, who has a friendly word for everyone.

I have hiked up and down to our sites with Reidar many times, inspecting them prior to fieldwork. Hiking with Reidar is always a pleasure. He is a nature lover who enjoys meeting a herd of reindeer or a batch of grouse chicks. As a fellow hiker, you become part of this positive experience. The only downside to hiking with Reidar is that he is in much better shape than I am, even in his seventies. Back at the car, I will normally be very exhausted while Reidar looks like he has just been on a stroll.

Late fall is the best period for artefact hunting at the ice patches. Reidar spends a lot of time in the high mountains then, monitoring sites and following the melt. He regularly calls us from the field to discuss the finds. I still smile when I think of a site call I got from Reidar back in 2014. We had done extensive fieldwork on this particular site the same year, collecting many finds. The melt continued, however, and Reidar checked the newly exposed areas for additional finds. On this particular day, Reidar discovered that there were also arrowshafts coming out of the ice, which only happens very rarely. I remember his excited voice: “I even saw an arrowshaft being flushed downslope by meltwater!” This is a process we thought might displace artifacts on our ice sites, and Reidar actually saw it happening!

Reidar was part of the field team when we discovered the Iron Age tunic at the Lendbreen Ice Patch in 2011. This was also when he and I had an experience that he ranks as his greatest moment in glacial archaeology. The other members of the team were busy documenting the tunic, and Reidar and I decided to proceed further along the edge of the ice on reconnaissance. We arrived at a large hollow that had been filled with snow and ice the year before. All the snow and ice had now melted and we made an incredible discovery … (more here)

In recent years, Reidar has spent a lot of time exploring the mountain range where Lendbreen is situated, especially the old routes crossing the range. Together with Espen Finstad, he has surveyed and mapped the routes. The results of this work are part of a forthcoming paper in the journal Antiquity.

Reidar’s Life Outside the Mountains

Reidar married Aud in 1976. They have two sons and three grandchildren. He started his own company in 1994, producing wooden furniture. He has provided many of the local hotels and mountain cabins with his products.

Reidar has now retired from his professional life as a furniture carpenter. He still uses his hands creatively, for instance when producing copies of prehistoric skis we have found in the ice.

Reidar also makes beautiful knives. To me, they are like a mirror of his archaeological survey work – competent, with attention to detail and with great results.

Reidar has received the Prize for Culture from the local municipality and (twice) the local Prize for the Environment, so his work is much appreciated locally.

The Mountain Man

As you will understand from reading this, Reidar did not become a mountain man. He always was a mountain man. He says himself that he was not born with skis on his feet as Norwegians are said to be, but with mountain boots instead. In the same way, his interest in the archaeology and history of his beloved mountains was with him from the beginning:

»I was going to the summer farm in Foss with my granddad when I was eight or nine years old. We were driving a horse wagon. There was no bridge over the river then. When granddad was getting ready to drive through the water, he noticed a stone lying on the bank. He lifted it up. There was a small hole in it. “Strange one”, he said and threw it away. I found it interesting and collected it. It was lying in a drawer until 1999, when I realised that it was an artefact and handed it in. It turned out to be a whetstone from the Viking Age or the Medieval Period.”

I know I speak on behalf of everyone involved in Secrets of the Ice when I say: All archaeological programmes and projects should be blessed with a Reidar.