Human remains from the ice have always received a lot of public interest. Almost everyone has heard about Ötzi, the 5200-year-old iceman from the Tyrolean Alps. But have you heard about Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi – the iceman from British Columbia? If not, you are seriously missing out on one of the most fascinating finds from the ice.

The Discovery

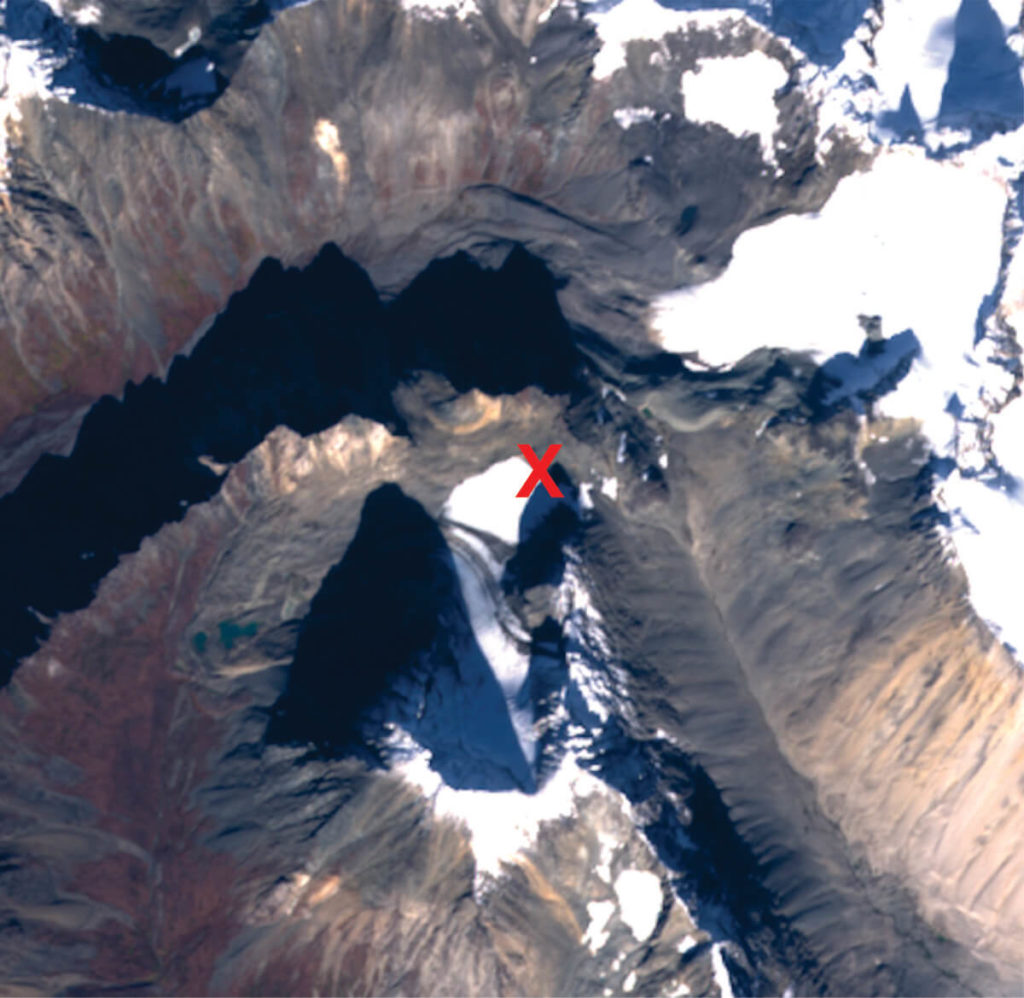

August 1999. It had been the hottest year on record in British Columbia, Canada, and the glacial ice was melting fast. Three hunters were looking for Dall’s Sheep in the remote mountains of the Tatshenshini-Alsek Park. On approaching a glacier, they could see something lying on the ice. Closer inspection revealed it to be an animal skin. Near it, they discovered a gruesome sight – a human pelvic bone, with attached legs disappearing into the ice. Checking the ice around the find spot, they also made other discoveries, including a small object with a wooden handle, still in its sheath.

The hunters took along a few of the artefacts for proof of the find, but otherwise had the good sense not to disturb the site. If only Ötzi the Iceman had been treated in such a gentle way (read more here). Once the hunters had hiked out from the park, they immediately contacted the archaeological authorities. The archaeologists naturally became very excited when they heard about the human remains and the artefacts. The small object with a wooden handle, brought along by the hunters, turned out to be a knife.

The Archaeological Investigations of the Find Spot

Archaeologists and representatives of the local indigenous populations visited the find spot the next day, using a helicopter to access the remote location. They confirmed that this really was a human body melting out of the ice. A week later, a proper site team arrived and investigated the find spot over two days.

Ice movement had divided the partly mummified body in two. The torso and the lower part of the body were 2-3 metres apart. The head was missing, and the lower part of the legs, including the feet, were skeletonised.

The field crew found several artefacts in addition to the ones removed by the hunters. These artefacts include a very fragmented robe (the animal skin noted by the hunters), a beaver-skin bag, a hat, a copper bead and wooden sticks.

As the glacial ice continued to melt, further finds appeared at the find spot in 2003 and 2004. Among these finds were human bone, including bones from the previously missing skull. The find spot had melted completely out by 2004. This means that all the preserved bones and artefacts associated with the mummy are now recovered.

Surveys of the ice-free terrain away from the find spot revealed a number of wooden artefacts, mostly sticks, which are probably not related to the human remains. They are more likely to be an indication that this was a known route, where many individual travellers had left behind objects over the years. This is a common situation, known from other mountain passes, also here in Innlandet County, Norway, where we work..

The local indigenous population, the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, named the person Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi – The Long Ago Person Found.

The Investigation of the Human Remains

The examination of the human remains revealed that they belonged to a young man of about 18 years of age. He had been c. 170 cm tall and appeared to have been in good health at the time of death. DNA analysis proved the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the heart and lungs, the bacteria that causes tuberculosis. The intestines contained large numbers of fish tapeworms, probably a result of eating raw or undercooked fish. Evidence from pollen indicates that the death happened in late July or August.

By analysing the contents of his stomach and bowels, it became possible to reconstruct his travel route in the days prior to his death. The lowest bowels contained marine foods, with meat from caribou or bison found further up. This shows that he travelled inland from the sea approximately three days before he died on the glacier.

Isotopic analysis of bone and tissue revealed that Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi ate food with a marine origin for most of his life. Even though found inland, he probably lived on the coast. In the last year of his life, the diet changed. He started eating more food from land mammals. This could mean that he started making extended trips to the inland during this period.

DNA-analysis of the human remains and of living members of the First Nations revealed that Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi was related on his maternal side to 17 living members of the Wolf/Eagle clans of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations.

The Artefacts

The artefacts found with Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi have been studied in great detail.

The well preserved basketry hat is woven from thin wooden fibres, which are probably from Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis). A headband is attached to the inside. The hat also had remains from a hide chinstrap attached to the headband. It showed repairs using sinew. Remains of red ochre can still be seen under magnification, so the hat was originally brightly coloured.

The knife was 14 cm long. It has a wooden handle made from Hemlock (Tsuga sp.) and a short iron blade. The blade is secured using hide lashing and backed by a piece of antler. The knife has a preserved sheath. Even though the local population did not smelt metals, they used iron for tools prior to European contact in the late 18thcentury. Iron could be acquired either through trade or from a shipwreck. Soon after contact, wrought iron became common.

The copper bead is 8 mm in diameter and 1.5 mm thick. It has two sinew threads attached to it. At the time of loss, both native and traded (smelted) copper would have been available as raw material for the bead. A spectrometric analysis has shown that the raw material for the bead is native copper.

The robe found together with the human remains was blanket-shaped. It was made by sewing together nearly a hundred small pelts. Red ochre mixed with salmon fat was applied to many of the seams. DNA analysis revealed that the pelts were from ground squirrel, while the sinew came mostly from moose. In two cases, coarser sinew for repairs turned out to be from Blue Whale and Humpback Whale – another link to the coast.

A bag made from beaver skin was also found, but it was poorly preserved.

In addition to the artefacts, there were finds of biological material, including flesh and scales from Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka), probably brought along as food by Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi.

When Did He Die?

The age of Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi has been a matter of some controversy. Initial radiocarbon dates on the clothing (the hat and a robe fragment) gave a date of at least 550 years. However, additional radiocarbon dates, including two on the body itself, put the find in the period AD 1720-1850. New radiocarbon dates on the hat and robe fragments fall within this period as well. Why the first two dates were off by several hundred years remains a mystery.

Radiocarbon dating also revealed that the dead person had lived on a primarily marine diet, even though he was found far inland. The marine diet is shown by the high levels of the carbon-13 isotope. This result matches the other isotope work described above.

Why Was the Body Preserved?

Contrary to popular belief, glacial ice is not a good place for preservation of human bodies. Most glacial ice moves, which tears apart human bodies stuck inside the ice or intermittently exposes it to the elements (read more here and here). So why was the body of Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi still relatively well preserved?

Careful study of the find spot of Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi revealed that the body lay in stagnant ice, i.e. stationary ice that does not flow downhill like in a normal glacier. Three protruding peaks of bedrock had stopped the glacial flow from reaching the find spot. Even so, the human remains were not intact.

The break-up of the body was probably caused by smaller movements of the ice, linked to ice melt. Analysis also revealed that the parts of body had been exposed previously, probably in the years prior to the discovery. This led to the head and feet skeletonising and detaching from the torso. These bone parts were then displaced by wind and meltwater, but were later found near the find spot of the body as the ice melted away.

If Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi had died outside the area of stagnant ice, we would never have heard of him. The preservation of his body and his artefacts was a random piece of luck, just as it was for Ötzi. This also tells us that he is unlikely to have been the only person to perish in the remote mountains of the Tatshenshini-Alsek Park. He is just the only one to have been preserved.

How Did Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi Die?

The examination of the human remains did not shed any light of the cause of death. With the find spot outside the glacier flow zone, we can rule out a fall into a crevasse as the reason the young man died. It appears likely that he died of exposure during the crossing of the glacier. Weather in the high mountains can change quickly, and if a storm broke during his glacier crossing he would have stood no chance (more on deaths in the high mountains here).

The Reburial

The contemporary cultural context of the Iceman from British Columbia is completely different from Ötzi the Iceman from the Tyrolean Alps. The investigation of the find spot and the study of the remains had to happen with the approval of and in coordination with the local First Nations. In the Tatshenshini-Alsek National Park, First Nations have sole authority over culture and heritage sites.

The remains of Kwaday Dän Ts’inchi were treated in accordance with the wishes of the First Nations. This is why there are no pictures available of the mummy, and why it never ended up on exhibition like Ötzi. Instead, the human remains were cremated in 2001 and buried in a cairn near the find spot. When additional human bones melted out in 2003 and 2004, they were studied on-site, and buried with the cremated remains.

More Information on the Find

If you would like to know more about Kwäday Dän Ts’inchi, I can recommend the 2017 publication of the find. This book not only goes into detail about the find and the results of the scientific analysis, but also describes the local cultural context. It is a great publication, available from the Royal British Colombia Museum.