Mountain glaciers are retreating due to global warming. Surprisingly, this creates a boon for archaeology. Incredibly well preserved and rare artefacts emerge from melting glaciers and ice patches in North America, the Alps and Scandinavia. A new archaeological field has opened up – glacial archaeology. The archaeological finds from the ice show that humans utilised the high mountains more intensely than previously known – for hunting, transhumance and travelling. New important discoveries appear each year, as the ice continues to melt back.

As glacial archaeologists, our dream discovery is a site where an ancient high mountain trail crossed non-moving ice. On such sites, past travellers left behind lots of artefacts, frozen in time by the ice. These artefacts can tell us when people travelled, when travel was at its most intense, why people travelled across the mountains and even who the travellers were. This information has great historical value.

There are several glaciated mountain passes in the Alps where incredible discoveries have emerged from the ice. Remember Ötzi? Here in Norway, almost all of our ice sites contain remains from reindeer hunting. However, would it be possible to find a glaciated mountain pass here with all its potential treasures? The hunt was on.

Fieldwork at Lendbreen Starts

August 4th 2011, the year of the big melt. We were surveying at 1900 m, along the upper edge of the Lendbreen ice patch. It was no coincidence that we were working here. In the 1970s and 1980s, local mountain hikers reported several artefacts from this site to the archaeological authorities, including a completely preserved Viking Age spear.

Previous days of survey led to the discovery of the usual arrows and scaring sticks, which showed that reindeer hunters were active here during the Iron Age. On this day, however, we started finding bits of textile, leather and other artefacts that are not common on hunting sites. What was going on?

The Discovery

While most of the crew started documenting the finds, two team members went ahead. It was a foggy day, and the fog just got denser as they progressed. Suddenly, they stumbled upon a strange wooden object. It looked like a giant slingshot, more than a metre long.

Then the fog lifted, and a large and shallow depression in the ridge appeared. When we were here the year before, snow and ice had filled the depression. The warm summer of 2011 had melted all of this, and exposed the bare ground in the process. As the two team members progressed into the depression, they had to be careful where they put their feet. Artefacts and horse dung were everywhere.

One of the two team members got his mobile phone out of his inner pocket and called the documentation team. He had to focus to keep his voice steady: “Guys, pack up your equipment and meet us in basecamp. We need to talk.”

We had hit the mother lode.

Rescuing the Artefacts

There were a lot of excited archaeologists in basecamp that evening. It was an incredible discovery, but we knew we had to act fast. Snow can arrive at any time in the high mountains, burying all the artefacts beyond our reach. In the following days we worked from dawn to dusk to document and collect the many artefacts in the depression before winter snow arrived. Thanks to a great effort by the team, we were able to complete the work in time.

It turned out that this frantic fieldwork was only the beginning. The Lendbreen ice patch continued to melt in the years that followed and more artefacts emerged from the ice. We have undertaken fieldwork at the site from 2011 to 2015 and again in 2018, 2019 and 2023, each time collecting many finds.

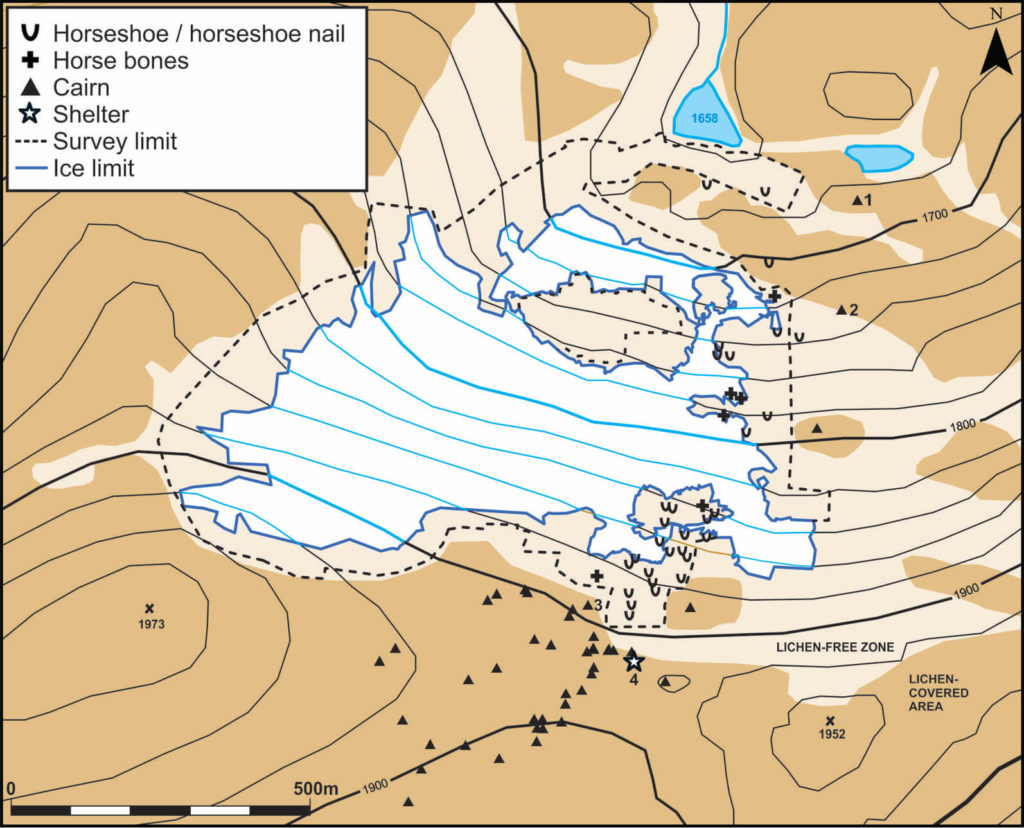

The survey at Lendbreen now covers c. 250,000 square metres, which equals 35 football fields, except that these football fields are on a 30-degree slope and the playing field is a combination of loose scree, bedrock and ice. To our knowledge, this is the largest glacial archaeology survey ever conducted.

It has been a demanding fieldwork in often appalling weather conditions. However, the reward has made it all worthwhile. The results from the fieldwork have made it clear that we have indeed discovered a lost mountain pass – the dream site for glacial archaeologists.

The Lost Mountain Pass

The lost mountain pass at Lendbreen is an incredible archaeological site. It has yielded hundreds of finds from ancient travellers, including clothing, dead packhorses and remains of sleds from the period AD 300-1500. It also has preserved cairns marking the route, and even a stone-built shelter in the pass area.

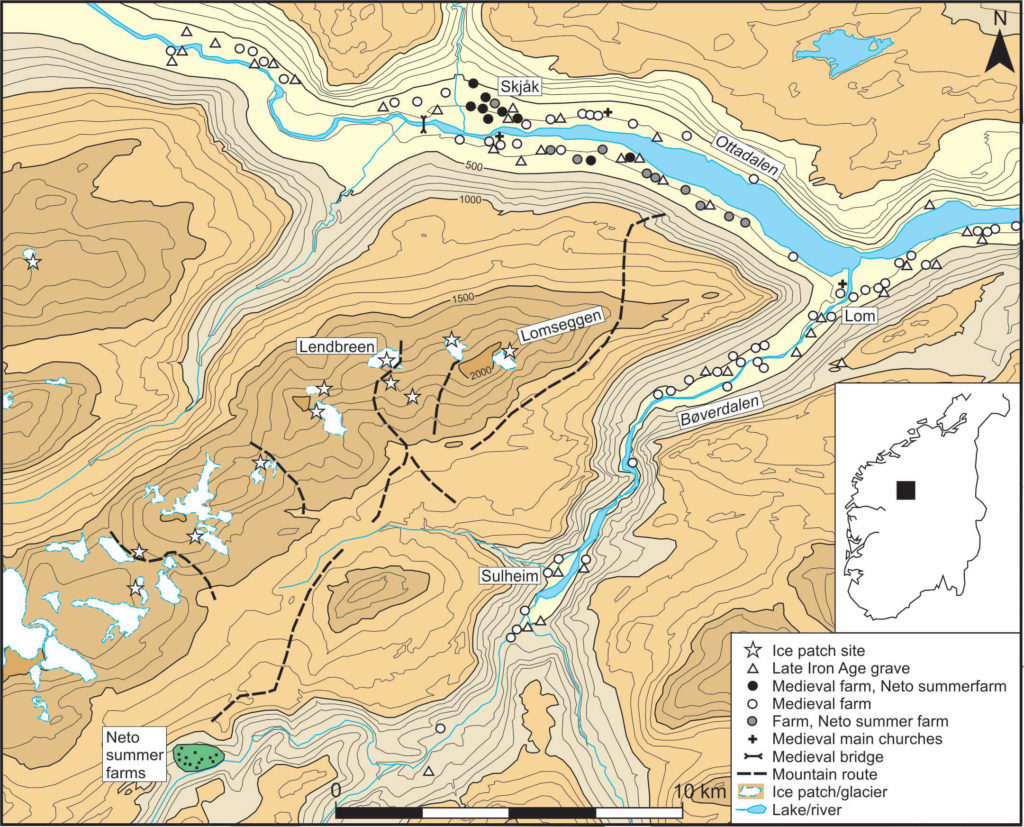

We knew from oral history that local people had crossed the Lomseggen ridge (c. 1900 m) through three known passes en route to or from their summer farms. Remarkably, the glaciated pass at Lendbreen is not among the known passes, even though finds and structures clearly show that it must once have served the same purpose.

Archaeological Ice Sites are Different

Before we dig into the details of the Lendbreen site, it is useful to know that archaeological ice sites in the high mountains are quite different from regular archaeological sites in the lowlands. There is a lot of artefact displacement by meltwater, ice movement and wind, blurring the original patterns of distribution. Simply put: We only rarely find artefacts where they were originally lost. At Lendbreen, four pieces of the same Bronze Age ski fitted nicely together. However, their find spots were up to 250 metres apart. Thus, caution is necessary when we try to interpret the artefact patterns.

Packhorses used the route crossing Lendbreen when snow covered the rough terrain. Thus, the artefacts were very likely originally lost or discarded on snow. However, until the big melt in 2019, nearly all the finds recovered in the pass area lay on the ground. This is in fact quite normal on archaeological ice sites. The artefacts melted out one or more times since their time of loss on the snow and ended up on the ground, only to be re-covered by snow and ice (read more about ice patches and glaciers as archaeological sites here). Finding the artefacts on the bare ground today does not mean that they were originally lost when the area was free of snow and ice. Misunderstanding this fundamental issue was what got the Ötzi investigation off on the wrong foot (read here).

The Preservation of Artefacts

The glacial ice preserves artefacts of organic materials, such as wood, bone, wool and leather. Wood, birch bark and bone preserve best of these. They are often the only materials left on sites that are repeatedly exposed. Textiles and leather disappear more rapidly. This means that we must be careful not to over-interpret maps of artifact distribution. Differences in preservation may cause some of the patterns. One example of this is the clear concentration of artefacts and horse dung in the depression just below the pass. This is likely the result of good preservation conditions there.

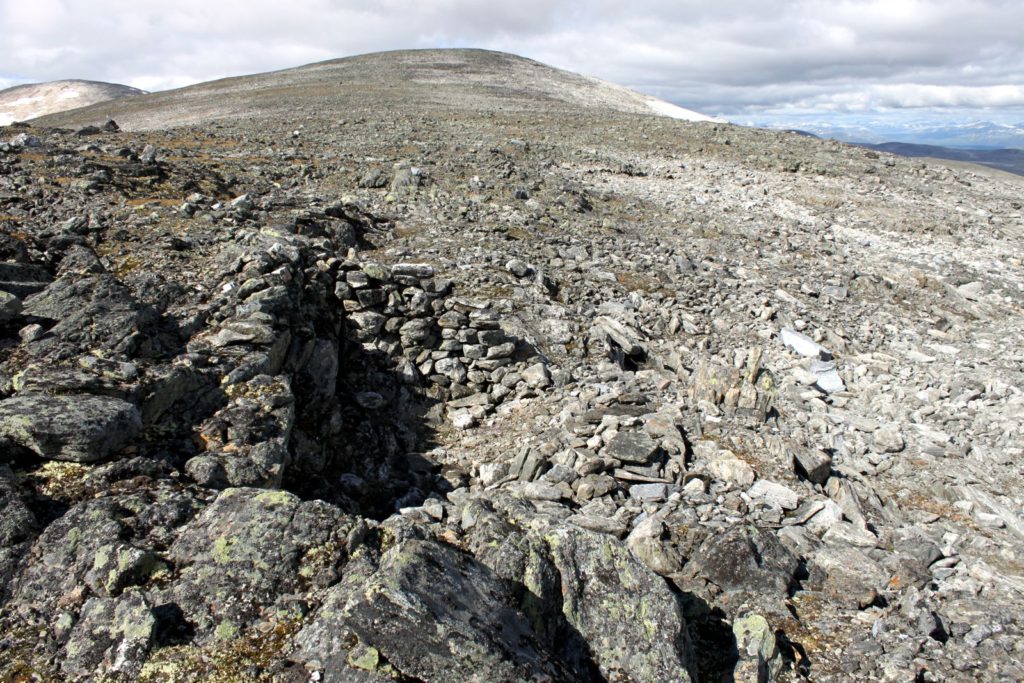

The Cairns and the Shelter

Luckily, artefacts are not the only objects that show where the route crossed the ice. A line of cairns shows the route coming up the Lendbreen ice patch from the north and going down on the southern side. In the pass area, there is a large number of cairns of varying sizes and shapes and even a stone-built shelter.

Other routes crossing the Lomseggen ridge do not have nearly the same amount of cairns and Lendbreen is the only one with a shelter. This singles out Lendbreen as a pass of special significance. You get the impression that maybe not all of the travellers here were locals. Therefore the route needed better markings and to be provided with extra protection. The high number of large and small cairns in the pass does remind one of the cairns built by tourists today, as memorials of their visits.

The Packhorses

Along the line of cairns, we have found bones of packhorses that died during the crossing of the ice. The earliest of these bones dates to the 5th-6th century AD. Lendbreen is an ice patch without crevasses, so we can rule out falling into a crevasse as a cause of death for the packhorses. The trip over the pass was quite short, so lack of fodder is also out. More likely, the packhorses suffered a fall and a broken leg or they died from exhaustion (read more about high mountain pack animals here).

There are also a number of horseshoe finds. The iron horseshoes are heavy and do not displace as easily as the light organic finds. Together with the cairns, they are a secure pin-pointer to where the route crossed the ice.

The Horse Dung

In the pass area where preservation conditions are better, there are thousands of pieces of horse dung. Radiocarbon dates of this dung have yielded Late Iron Age and Medieval dates. There is actually so much dung in the pass area that the ice has a brownish colour in some places. There must have been many horses going through the pass.

The route crossing Lendbreen seems to have worked in an opposite way to mountain passes in the Alps and in the Himalayas. In these mountains, glacier advances often closed passes during climatic cold periods. In contrast, the route crossing Lendbreen would only have allowed horses to pass during periods with snow covering the rough ground.

The Sled Remains

Before we started fieldwork at Lendbreen, we heard a local story about the discovery of a sled there in the 1960s. There are a number of such stories of fantastic discoveries from the ice in our county (including one about a mammoth, which absolutely cannot be true), and we did not put too much faith in it. We checked the area, where the sled was supposed to have melted out but had no luck.

The fieldwork in the pass area has shown, however, that there may be some truth to the story. The giant slingshot-like object found in the pass, together with a similar piece, is what is known locally as a “tong”. They were used to secure the load on sleds carrying fodder (read more here).

Leaf Fodder

Incredibly, we may even have found remains of such fodder. We recovered more than 60 cut branches from the site, mainly in the pass area where preservation conditions are good. Specialists have examined them. Their analysis shows that the branches probably are the remains of leaf fodder. This is not a trivial question, as transporting leaf fodder on sleds or on packhorses at nearly 2000 metres during wintertime must surely have been a daunting task. We have radiocarbon-dated five samples of the leaf fodder, which cover the period AD 700-1400.

Other finds point to transport as well. There are a number of finds of withy locks, wooden plugs and other artefacts, which were likely used for securing the loads on packhorses or on sleds. As such artefacts are rarely preserved in other contexts, their exact function remain somewhat uncertain.

The Clothing and Textile

It is quite typical to finds remains of textiles in mountain passes and this is also the case at Lendbreen. The most famous find from Lendbreen is a complete Iron Age tunic, dated to AD 300, the oldest piece of clothing found in Norway.

There are other intriguing textile finds from Lendbreen, most notably a very rare Viking Age mitten. It is made from patches of different textiles.

We also discovered several shoes made from hide at Lendbreen. The best preserved is from the 11th century AD. The shoes had the hairs on the outside, to provide a grip on the snow.

Why are there so many finds of clothing at Lendbreen and in other mountain passes? A gust of wind may have taken the mitten. Shoes may have been discarded after use. The loss of a complete tunic is harder to understand. It may represent clothing discarded during the last stages of hypothermia (read more here).

In addition to the clothing, there are more than 50 textile rags in the pass area. Such rags are also occasionally found on hunting sites, but never in such numbers as at Lendbreen. We discuss possible reasons why they were lost in this blog post.

The Everyday Objects

The ice at Lendbreen also contained a number of well-preserved objects from everyday life. They are among the most fascinating finds from the site. Most of the objects, but not all, are easily recognisable as to their function, as similar objects were in use locally until recently.

A 70 cm long wooden object, ornamented with geometric patterns, was an enigma to us. A radiocarbon sample dates it to c. AD 800. We put a picture of it on our Facebook page. We immediately received an identification by several of our followers with an interest in historical textiles. It is distaff, a tool used in spinning. It is designed to hold the unspun fibres, which are wrapped around the distaff.

Another remarkable find is a wooden whisk, dated to the 11th century AD. Such whisks are still in use in Norway today. Our whisk is pointed at one end, which is not the normal shape. This leads us to believe that it may have served a secondary purpose, such as a tent peg.

Knife, Bit and a Runic Inscription

A small and worn iron knife with a handle in birchwood emerged from the ice in the pass area. Knives also appear on hunting sites. Thus, we cannot be sure whether a reindeer hunter lost it. However, the knife is somewhat smaller than other butchering knives we have found. In addition, radiocarbon dating places the knife in the 11th century AD. There are no other hunting finds at Lendbreen from this period. The knife was probably lost by a traveller.

Another artefact that we were originally mystified by was a small wooden object with pointed ends. It turned out to be a bit for young animals, mainly goat kids and lambs, to stop them from suckling their mother. A local, elderly woman identified it. She had used such bits (in juniper) in the 1930s. Ours is also in juniper, but radiocarbon-dated to the 11th century AD.

Walking sticks, complete or broken, are quite common at Lendbreen. One of them carried a runic inscription with the name of its owner – Ivar. The type of runes and the radiocarbon date of the stick both point to the 11th century AD.

The History of the Pass

The radiocarbon dates of the finds tell us that people started using the pass around AD 300. There are no transport-related finds earlier than this, and it is unlikely that earlier finds were lost due to exposure. The pass area contains a number of other finds earlier than AD 300, such as a 4000-year-old bear skull and a Bronze Age arrow. Since they are preserved, earlier travel-related finds should also still be present.

The AD 300 start date fits well with what we know about human activity in the surrounding areas, mainly based on pollen analysis. Human impact on the landscape, both in the valleys and in the mountains, increased around this time. The use of the pass is thus linked to increasing economic activity in the region.

The transport through the mountain pass at Lendbreen peaked markedly around AD 1000 and then declined through the Middle Ages. The time of the peak, which is the transition between the Viking Age and the medieval period here in Norway, was a time of increased urbanisation and commerce, so this fits well. It is harder to understand that the activity in the pass declined after that (see below).

Where Did the Route over Lendbreen Lead?

Based on the cairns found during our survey of Lendbreen and the Lomseggen ridge, the route over Lendbreen led to the Neto summer farms. This could have been the end destination, but it was also possible to continue from Neto to the Sognefjord where you could acquire salt, barley and stockfish and sell local products, e.g. from reindeer. Therefore, the traffic through the Lendbreen pass was both local and long distance (read about our incredible discovery, when we followed the trail towards Neto).

The finds give us limited, but important information about the transport of goods through the mountain pass. The leaf fodder was one commodity. This was local goods, transported on sleds in the winter to provide much needed extra fodder to carry the farm animals through the winter. We also have one find of raw wool, packed in a container made of birch bark. Based on historical sources, farm products such as cheese and butter were transported from the summer farms back to the main farms. That could have happened here as well. In addition, local products, such as reindeer pelts and antlers, were commodities for which there was a market in towns, even outside Norway. Some of these products may also have gone through the Lendbreen pass.

The route over Lendbreen only works with horses when snow is covering the rough ground. Thus, we believe that the use of the route was mainly in late winter or early summer.

Why Was the Pass Abandoned?

The number of finds from the Lendbreen mountain pass declines during the medieval period. This is remarkable, as trade and commerce increased up to AD 1350, and so did the population. The youngest find is a horse cranium from c. AD 1700. It is still not quite clear why the traffic through the pass declined already from the 12th-13th centuries AD.

The Black Death led to a dramatic population decrease in the mid-14th century. This, in combination with the arrival of the Little Ice Age, may have reduced human activity in the high mountains. When large-scale summer farming resumed around 1600, Lendbreen was no longer an important pass, and soon went out of use. Instead, three other passes were used and preserved in local oral history. The Lendbreen pass was lost.

Why the route using the Lendbreen mountain pass went out of use is not clear. Perhaps its use was always more linked to long distance travel than local travel to/from the summer farms. Maybe the long distance travel through the Lendbreen route had declined during the Early Medieval period, and other routes substituted it. This remains speculative.

The routes crossing Lomseggen were finally abandoned in the mid-19th century, when better roads were built in the valleys, linking the Neto summer farms to Skjåk. This made it possible to bring animals to the summer farms at Neto in an easier way than crossing the nearly 2000 metre high ridge.

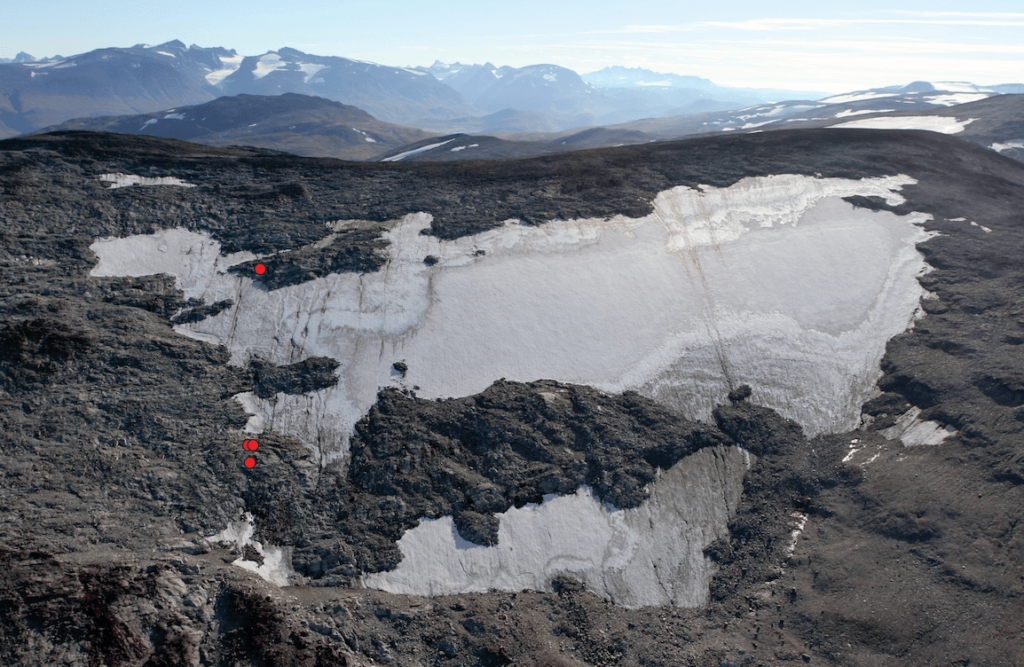

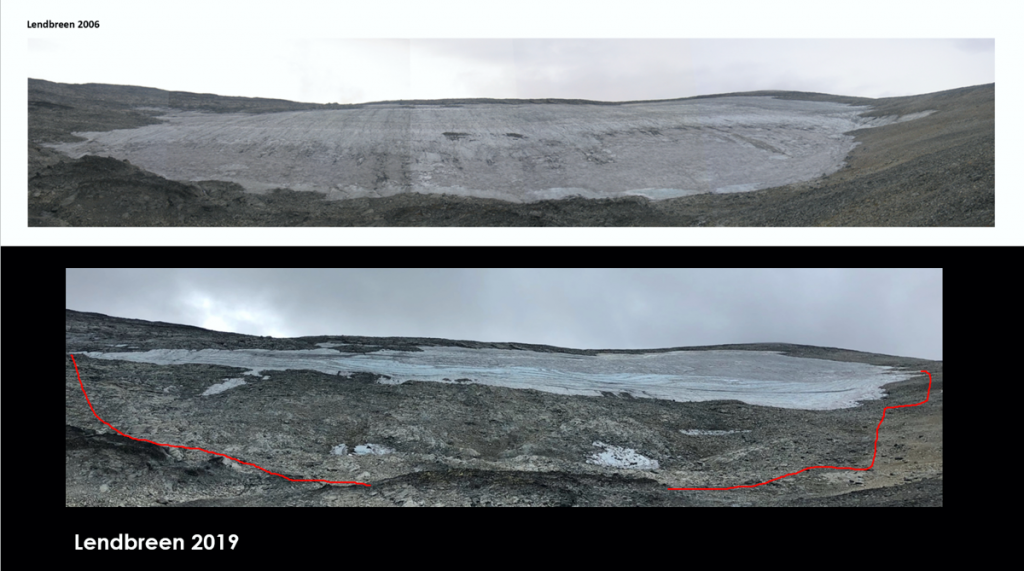

The 2019 Big Melt

After Antiquity accepted our paper on Lendbreen, the Lendbreen ice patch suffered an incredible melt in the autumn of 2019. Finds appeared on the surface of the ice, showing that the melt had reached ice layers not previously touched by melt. Horse dung littered the ice in the pass area. Basically, nearly all the remaining ice from the time of the route melted out.

The 2019 melt probably was Lendbreen’s swan song, concerning finds from the mountain route. What a finale it was! A wooden box with the lid still on turned out to contain a beeswax candle. A radiocarbon date placed it in the 16th century AD.

We found a beautifully preserved horse snowshoe, which turned out to be from the 3rd century AD – the earliest transport-find from the pass. Iti s a neat confirmation of our hypothesis that humans and packhorses used the pass when snow covered it. We also found a near complete skeleton of a packhorse. Even a 500-year-old dog with a collar and leash melted out of the ice.

More Pass Sites Will Appear

The ice in the high mountains will continue to melt back as temperatures keep rising. The ice that contained the remains of the lost mountain pass at Lendbreen is probably gone now. However, future melt will uncover other glaciated pass sites. Just after finishing work at Lendbreen in 2019, finds started melting out in a mountain pass further west on the ridge. During a quick survey on the last day before winter snow arrived, we managed to recover an Iron Age shoe and a piece of leaf fodder here. There will be more to come.

You can download our Antiquity paper here.