Ötzi the iceman is the holy grail of glacial archaeology, nothing less. The discovery of the 5300-year-old mummified body and the associated artefacts created a media frenzy and great public interest. Today, 250,000 people visit the Ötzi Museum in Bolzano each year to get a glimpse of Ötzi and the exhibited artefacts. A wealth of scientific papers, popular books and documentaries are available.

Ötzi melted out of the ice in 1991 in a gully at the Tisenjoch pass close to the Italian/Austrian border. The original interpretation of the find by the Innsbruck-based archaeologist Konrad Spindler was that Ötzi fled to the mountains in the autumn after a conflict. He froze to death in the snow-free gully. Snow and ice quickly covered him, and then a moving glacier. Ötzi remained encased in ice until he melted out in 1991. How else could the preservation of the body and artefacts be explained?

In many ways, Ötzi was a surprising and odd find when he was discovered. Even though archaeological finds melted out of the ice in Norway decades before Ötzi’s discovery, this was not well known in the wider world. Thus, when Ötzi appeared, he was a bolt from the blue for the Austrian and Italian archaeological milieu. From the start, scientists believed that Ötzi was a unique find, preserved by miraculous circumstances – a freak of nature event. Otherwise, there would surely have been more such finds. It was six years before the first mass melt-out of archaeological finds from the ice in Yukon in 1997 and a few years later in the Alps and Norway (more on the history of glacial archaeology here).

When the first examples of a new type of find are discovered, they will sometimes appear surprising and odd. As time passes and more finds emerge, this situation typically changes. The earliest discoveries no longer appear peculiar, but fit a pattern that was not visible initially. We have witnessed the same phenomenon during our glacial archaeology work here in Innlandet County, Norway. Finds that initially appeared odd and challenging to comprehend, turned out to fit a pattern that was not apparent to us, when we first started.

Since Ötzi was discovered in 1991, glacial archaeology has developed as a new archaeological discipline, with its own methodology and a deeper understanding of the complexity of ice sites. Presently, there are hundreds of sites and thousands of finds in various parts of the world. However, Ötzi is still an odd find. Similar very old finds sealed beneath moving glaciers are unknown. The time has come to ask the question: does the original Ötzi story still hold up?

We start at the very beginning.

The Discovery of Ötzi

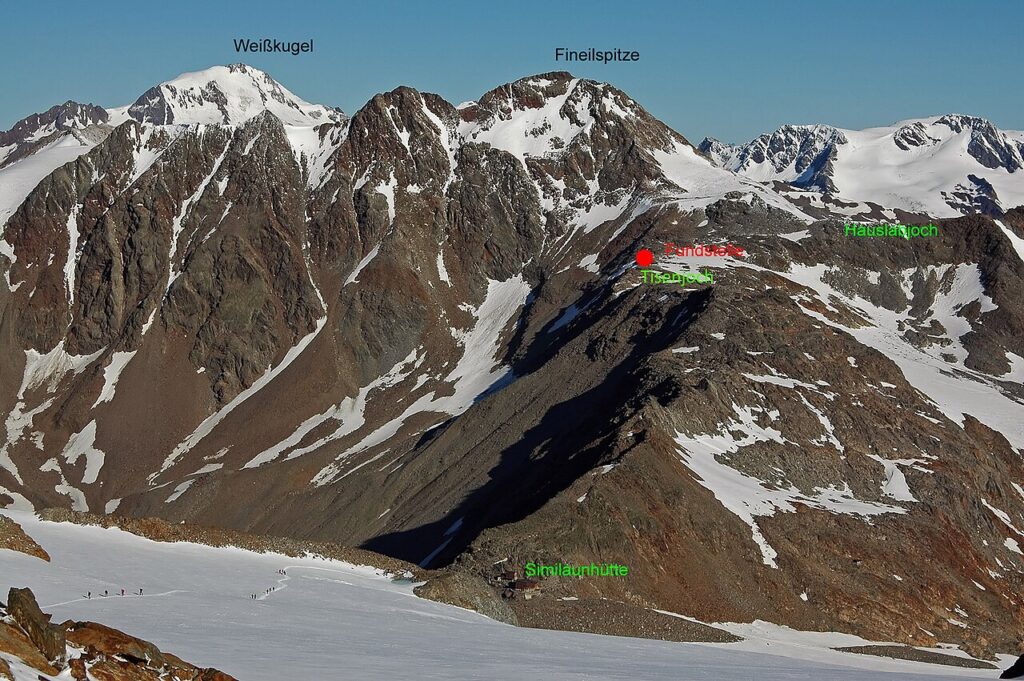

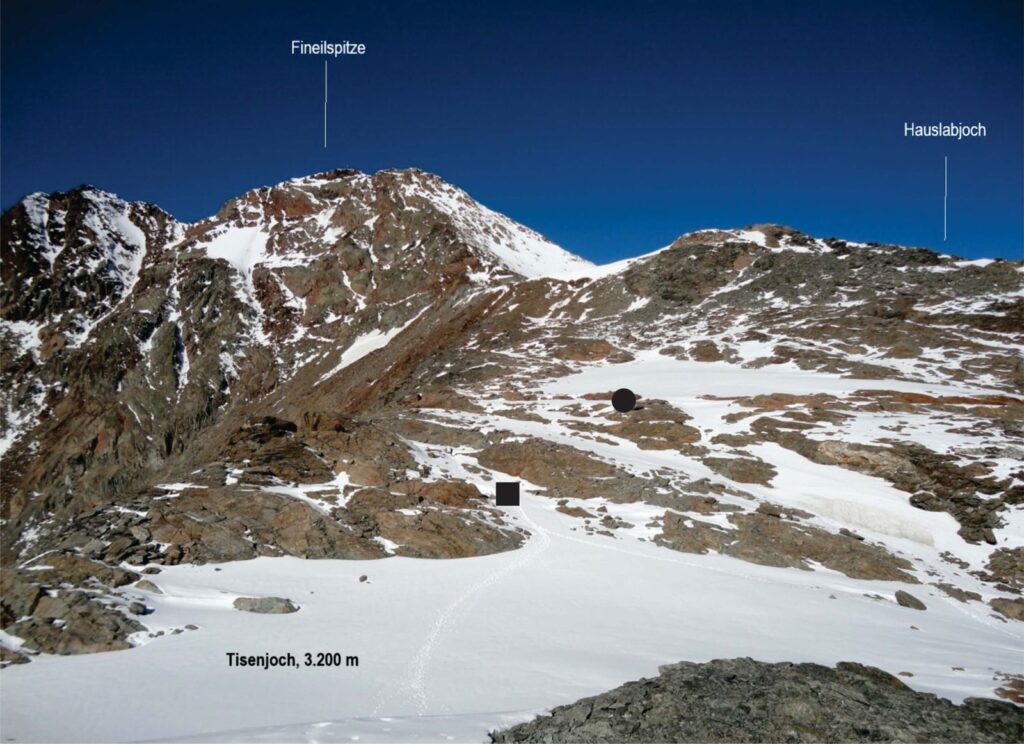

The German couple Helmut and Erika Simon discovered Ötzi on Thursday September 19 1991. His upper body protruded from the ice in a gully at 3,200 metres in the Tisenjoch pass on the Italian side of the Italian-Austrian border.

The Recovery of the Body and Artefacts

The Simons reported their find to Markus Pirpamer, the owner of a local mountain cabin, the Similaunhütte on the Italian side of the border. He informed the authorities on both the Austrian and the Italian side. Initially, it was not clear whether the find was on Austrian or Italian soil. Bad weather delayed the recovery of the body until Monday, 23rd September.

The authorities did not immediately understand the great age and significance of the find. Ötzi was not the only body to emerge from the ice in the Alps in 1991. It had been an exceptionally warm summer, and several other, more recent bodies had also melted out of the ice. Focus was on recovering the body, which is standard procedure, when the dead return from the glacial ice. A number of people visited the site to view the body before its recovery. They stepped on the fragile objects and removed artefacts prior to the recording of their locations. This was very unfortunate and led to the destruction of important evidence on the site.

When the Innsbruck-based archaeologist Konrad Spindler saw the copper axe found with Ötzi, he immediately understood that this was not a recent glacier body. It had to be at least 4000 years old. The ice mummy became an immediate sensation.

The Excavation of the Find Spot

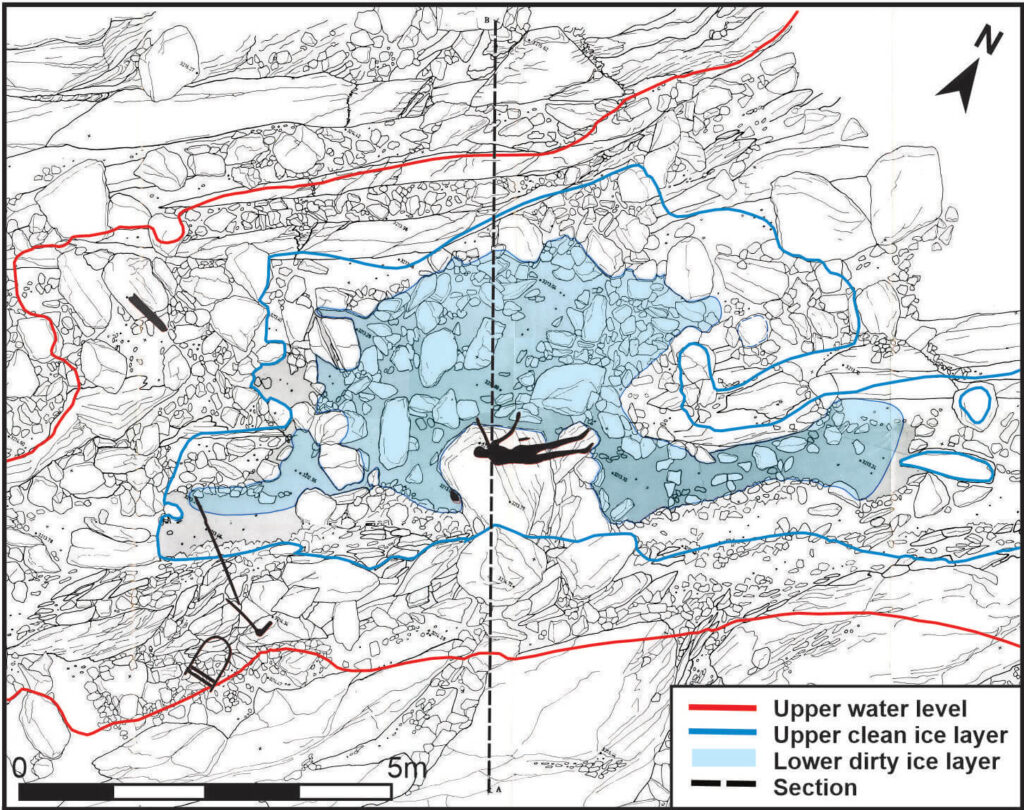

Archaeologists investigated the find spot shortly after the discovery, but the appalling weather conditions and the onset of winter quickly halted the fieldwork. A well-organized and thorough excavation of the gully took place in in 1992. The excavation led to the recovery of a few more artefacts and a number of fragments, and the collection of a large number of samples.

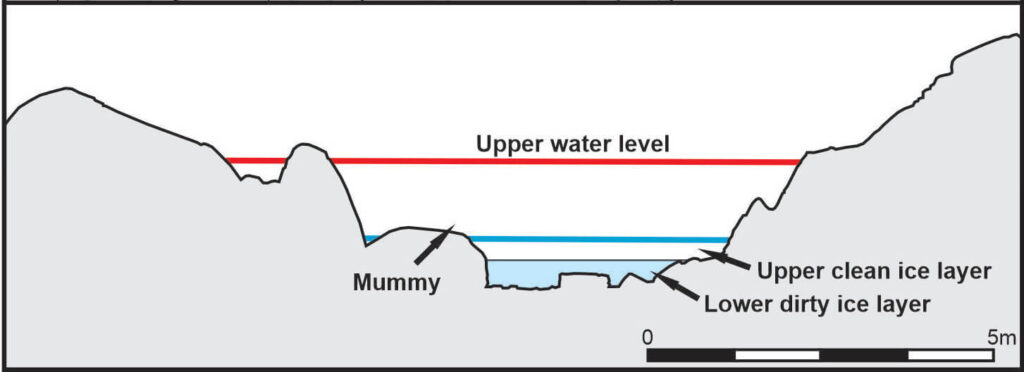

A painstaking reconstruction of the original location of the artefacts ensued, based on interviews with people who visited the site prior to the first proper investigation. It appeared that many of the larger artefacts had rested on the stones along the sides of the gully or in a thin layer of dirty ice at the bottom of the gully. Thus, the natural conclusion was that the gully had been free of ice and snow when Ötzi died. However, it was puzzling that the location of some of the artefacts was at some distance from the body, such as the quiver, which lay 7 meters away.

The Ötzi story

Together with two colleagues, the archaeologist Konrad Spindler in Innsbruck took charge of the investigations, with the collaboration of a number of colleagues from Austria, Italy, and other countries. Ötzi has been studied using state of the art methods. A large number of publications tell the story of his life, his death and his times.

Spindler’s Original Interpretation

The original interpretation by Spindler (also known as the disaster theory) was first presented in 1993 in his book: Der Mann im Eis (The Man in the Ice). Spindler believed that Ötzi fled across the mountains from the south in the late summer or autumn. Some of his equipment suffered damage in a violent encounter, and he had no time to repair it. Ötzi died in a snow-free gully in the pass. Exposed on the surface, he freeze-dried, which led to the exceptional preservation of his body. Then snow fell and covered the body and the artefacts. A short time later, a glacier covered the area, and buried the body and the artefacts for more than five millennia, like in a time capsule. The gully offered protection for Ötzi and his artefacts, so that the moving glacier did not crush them.

Spindler’s interpretation of the find was not unanimously accepted by his colleagues at the time. However, the attractiveness of the story has made it the official Ötzi story to this day. Perhaps the only major change is that the 2003 discovery of an arrowhead embedded in his shoulder has turned Ötzi from a victim of hypothermia into a murder victim.

More importantly in our context, however, is the work of the eminent botanist Klaus Oeggl in Innsbruck, who published a number of scientific papers based on samples taken from Ötzi himself and during the 1992 excavation. Starting in 1998, Oeggl has shed new light on the time of year for Ötzi’s death, on his death in the gully, and on his subsequent permanent burial beneath the ice, as claimed by Spindler.

Spindler’s Story is Still Alive

I visited the Ötzi museum in Bolzano in 2016, when Innsbruck was the venue for the world conference on frozen archaeology. As glacial archaeologists, the museum kindly treated us to a guided tour of the museum. Our guide told the story of the find – the original Spindler story told above, where a string of lucky coincidences led to the preservation and subsequent discovery of Ötzi. On the homepage of the Ötzi Museum, it still says explicitly: “The corpse lay in a 3-by-7-metre-wide gully and was thus protected from the destructive forces of the moving glacier. The rocky gully was probably free of ice when Ötzi died there. Subsequently, he must have been covered by snow and the glacier ice.” “The Glacier Mummy“, an excellent and very nicely illustrated book on the Ötzi find published by and sold at the museum, tells the same story.

The Question of Time and Place of Death

Spindler’s interpretation of the find was that Ötzi died in the snow-free gully. The estimate of time of death was late summer or fall. The basis for this conclusion was the discovery of a sloe near the ice mummy – sloes ripen in late summer. In addition, minute pieces of grain stuck to Ötzi’s clothing, and the idea was that they ended up there during threshing.

Doubts Arise

An important piece of independent evidence that Spindler’s assessment of Ötzi’s time of death was wrong appeared in 2001. Klaus Oeggl found pollen of hop hornbeam in a sample from Ötzi’s gut. These pollens are produced in March and April in the valley, where Ötzi came from. Fresh leaves of maple were also recovered from inside one of the birch bark containers found at the site. They point to a death perhaps a little later in the year – May or June? This time of year is a time of maximum snow depth in the Tisenjoch area. Even considering the windswept ridge where the find lay, snow would very likely have covered the gully, perhaps deep snow. How could Ötzi have died down in the gully then?

In 2010, a group of Italian researchers challenged Spindler’s disaster theory. They claimed that Ötzi had died in the valley in the spring and was transported to the site in the autumn. According to the researchers, Ötzi was buried on a stone-platform near the later find spot. They also believed that the mummy and the finds had been moved by recurrent thaw and re-freezing processes. The original Ötzi research group countered that this hypothesis just did not fit the evidence obtained from the investigation of the site. However, the discussion drew attention to the uncertainties associated with the natural processes on the site. The 1992 excavators also raised this point. They wrote in their 1995 report that recurrent thaw and re-freezing processes had probably displaced the mummy and the finds.

The Broken Equipment

Ötzi died in the spring/early summer, not in the autumn, and natural processes had affected the mummy and the finds. This takes us to the next curious aspect of the find – the broken equipment.

Some of the artefacts found with Ötzi were damaged (such as the quiver, an arrow and the backpack), and pieces were missing. The explanation given by Spindler was that the damage happened during a conflict or during Ötzi’s flight to the mountains, and he had no time to repair them.

However, there may be a simpler and more natural explanation for the broken equipment and missing pieces. We learned from a careful analysis of our Lendbreen site that there are a number of natural processes that affect artefacts lost on the surface of snow and ice. The simple version is that the artefacts may be displaced from the original place of deposition, they may break into pieces and the broken pieces may scatter. Often artefacts go through all three processes.

The snow and ice cover will melt away during very warm summers. Some of the artefacts originally lost on the ice and snow will melt out into hollows below. Such hollows are more protected from the elements and are more likely to preserve snow and ice over the summer. This means that they are good for artefact preservation. Artefacts that do not make it into such hollows are more likely to be lost over time due to higher levels of exposure. The exposed artefacts gradually disappear, with wood and birch bark being the last materials to be preserved.

The artefact distribution maps at Lendbreen Ice Patch show this pattern clearly. Pieces of wood and birch bark surround the edges of a large hollow with more favourable preservation conditions. Inside the hollow, textiles, leather and horse dung are preserved. Wood and birch bark are very durable. This is probably because they go through a natural conservation process of freeze-drying due to the cold and dry environment.

When the ice melts completely, the artefacts end up resting on the rock and stones below. This is not because they were originally lost there when there was no ice, but because the layer of ice and snow in between melted away at some point. During this process, meltwater and strong wind may disperse the artefacts. Once resting on the rocks, the artefacts may break into pieces, due to ice and snow pressure or being trampled by animals. After breaking into pieces, meltwater or strong winds may displace the individual fragments. At Lendbreen Ice Patch, we have found fragments of the same artefact hundreds of metres apart. Many of the artefacts have parts missing. That does not mean that people brought these items into the mountains in an already broken state. Natural processes damaged the artefacts on the site.

Ötzi and the state of his artefacts fits this general process well. The dispersed and broken equipment with missing pieces is likely to be a result of natural processes on the find spot, not a hasty flight. Ötzi died on the surface of the snow. When the snow and ice melted, his body and most parts of his equipment ended up in a gully underneath. The missing small parts never made it into the gully, probably because meltwater and wind displaced them. Once melted down on to the bare terrain below, snow and ice recovered the site.

Are there any traces of the artefacts that did not make it into the gully? Remarkably, there are, even though the excavation in 1992 did not extend outside the gully. Very poorly preserved remains of a birch bark vessel were found just south of the gully, outside the excavated area. These remains turned out to be part of a better-preserved birch bark vessel recovered from the gully. The find is in complete accordance with the Lendbreen find circumstances. This piece did not make it into the gully, perhaps together with other artefacts and fragments of less durable materials, now lost.

Ötzi’s Death and Broken Equipment

A conclusion in line with the evidence and in support of Oeggl’s work is that Ötzi did not die in the gully. He died outside it, or more precisely above it. His dead body most likely rested in/on the snows of late winter. After freeze-drying on the surface of the snow, he and most of his belongings later entered into the gully as the snow and ice surrounding him melted away. Whether this happened the same year, later and/or in several steps is not known. Natural processes on the site caused Ötzi’s broken equipment and the missing pieces, not a violent encounter prior to his death.

The Question of the Glacier

A central part of the original Ötzi story is that he died just as the climate was getting cooler. Snow and ice covered his resting place a short time after he died, sealing it off from the environment. Otherwise, the reasoning goes, the ice mummy and the artefacts would not have been preserved. This has even been used as an argument for glacier advance and climate cooling just when Ötzi died. As the ice built up, a glacier developed here. Since Ötzi rested in a protected gully, the moving ice of the glacier did not directly influence the find. Only 5300 years later did the glacial ice melt away and Ötzi reappeared.

This type of preservation is at odds with the way other ice finds from glacial ice are preserved. They are mostly found in association with ‘cold’ ice, i.e. non-moving ice that is frozen to the ground below. Such non-moving ice can be found in isolated ice patches and in non-moving ice fields attached to moving glaciers. Alpine glaciers, on the other hand, only yield more recent finds, which normally do not even date back to the medieval period. This is due to their downhill movement and renewal of the ice (more about that here).

Since the discovery of Ötzi in 1991, no other similar finds have appeared from gullies beneath glaciers, even though glaciers in the Alps have retreated substantially due to the ongoing warming. A number of human corpses and remains have emerged from the melting glaciers in the Alps and elsewhere, but none earlier than c. AD 1600 (more on this subject here). All the recent human remains were discovered on the surface of glaciers, not below them. An artefact assemblage similar to Ötzi’s, but five hundred years younger and without the mummy, appeared in the Schnidejoch pass in the Swiss Alps from 2003 onwards. This find was associated with ‘cold’ ice in a slope just below the actual pass. There is a glacier here as well, but further downslope.

What is the evidence that there was moving ice in the location of Ötzi’s find spot? The excavators of the site actually write on the first page of their 1992 excavation report that the topography of the area surrounding the find spot is not advantageous to the development of a glacier. There is no catchment area for a glacier here. The area is also quite flat, which would not have facilitated ice movement either.

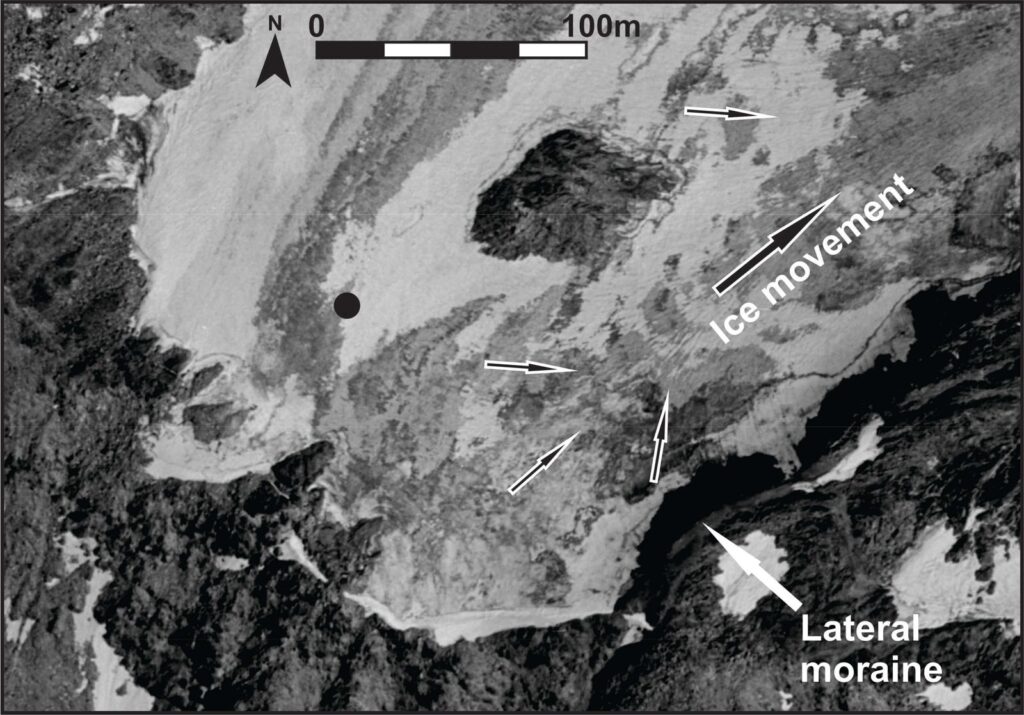

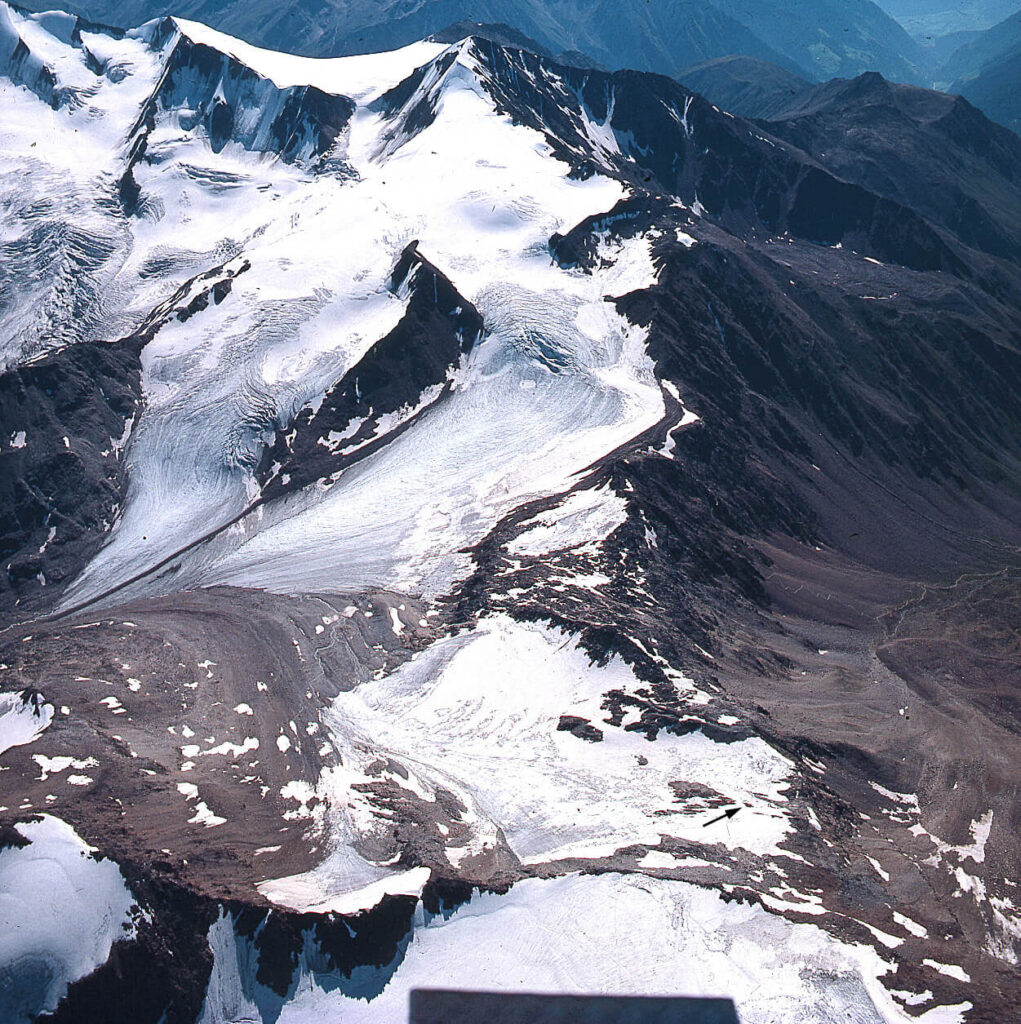

In a 1996 paper on the glaciology of the area, Baroni and Orombelli write that the Ötzi was found at the upper edge of the accumulation area of an alpine glacier. He was preserved in motionless ice inside a gully, protected from the shearing flow of the glacier.

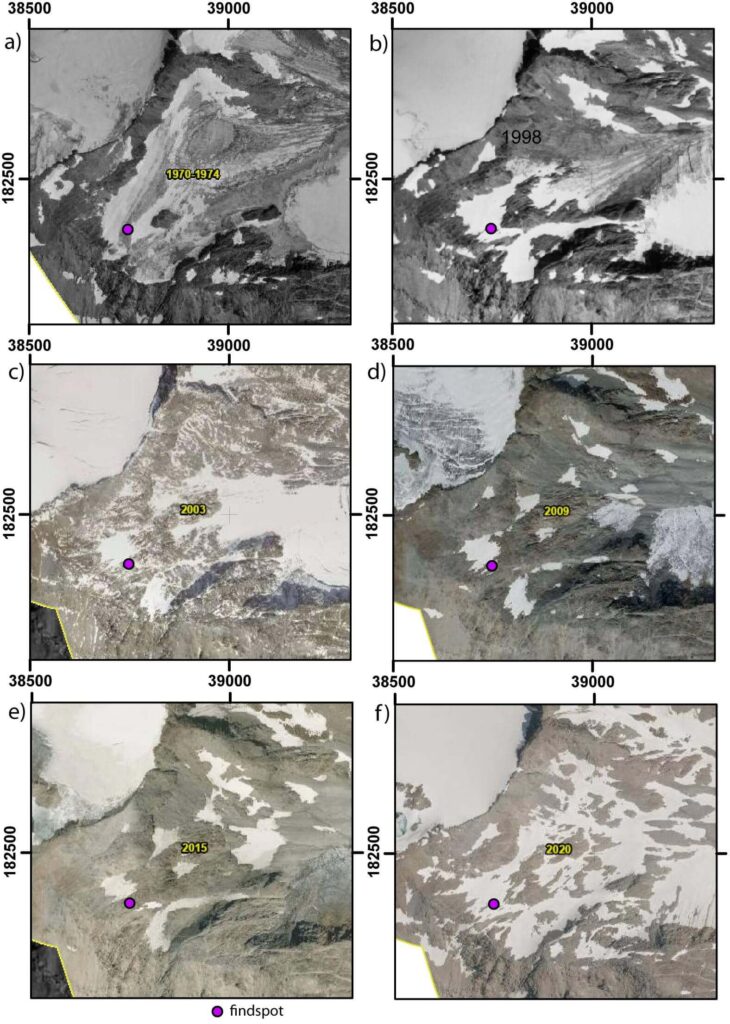

Austrian mapping authorities took aerial photos of the find spot in the early 1970ies. These pictures are available through the internet for import to a GIS (Geographical Information System). This 1970-74 picture (above) does not show visible signs of ice movement at the marked find spot. However, the first traces of stretch marks from ice movement are visible only c. 50 metres further east. There is also a lateral moraine deposited by a moving glacier present here, even though this moraine may date back to the termination of the last Ice Age.

This information fits well with the ground situation in the area (see picture above). The find spot is in a flat area, close to the highest point on the ridge. From the find spot, the terrain slopes down into a large gully in the area where the stretch marks are visible in the 1970ies aerial photo.

There is another piece of evidence that points against basally-sliding ice over the find spot. Several of the artefacts were not recovered deep inside the gully, but further up on the sides of the rock ledges and stones constituting the gully, and even outside the gully. If a glacier had ground its way over here, how could they have been preserved? Perhaps even more telling is an axe handle from the Tisenjoch, 500 years younger than Ötzi. It was found lying on open ground 50 metres south of the Ötzi find spot. How could it have survived a grinding glacier moving over the area?

There is one more way to investigate the question of a moving glacier at the find spot. That is to reconstruct the maximum ice thickness at the find spot at the end of the Little Ice Age (from the 14th century to the mid-19th century). This was when glaciers in the Alps were at their largest after the Ice Age. A map of the Tisenjoch published in 1878, just at the end of the Little Ice Age, shows the height contours of the ice at that time. We can compare this ice height with the height of the bedrock, now exposed by the retreating ice.

The calculation shows that even when taking the uncertainties of the old map into consideration, there was never enough ice thickness at or around the find spot for the ice to start sliding. The ice thickness was below 20 metres in 1878, probably closer to 5 metres. There needs to be 25-30 metres of ice for a glacier to start sliding at the bottom. In addition, the slope at the find spot is less than 10 degrees, which does not facilitate ice flow. Austrian glaciologist Andrea Fischer undertook this analysis for our new Ötzi paper. It is the final nail in the coffin for the idea of a moving glacier at the find spot.

Based on this discussion, a non-moving ice field developed over Ötzi’s resting place. Further downslope, this ice field became thicker, eventually developing into a classical moving glacier, which ground its way into the hillside. In the flat area of the find, the ice did not become thick enough for basal sliding to happen after Ötzi died here. It was ‘cold ice’, frozen to the ground.

Does it matter whether a moving glacier or a thin non-moving ice field developed over Ötzi’s resting place? Is this not just a technicality? Not quite. Thin, non-moving ice fields connected to glaciers are quite similar to isolated ice patches. They are less stable than glaciers, and more prone to periodic melt during shorter warming periods. If Ötzi was buried beneath a non-moving ice field of limited thickness, the body and the associated artefacts are more likely to have been repeatedly exposed to the environment. It would change the context of the Ötzi find from very special circumstances to quite normal find circumstances for ice finds.

The Question of the Time Capsule

The official story provides a single event situation with all the material found in the gully being related to Ötzi. This would be a remarkable situation in glacial archaeology. Ice sites tend to accumulate material over time, not preserve one single event only, and especially not in mountain passes, where there is often quite a lot of human and natural activity over time.

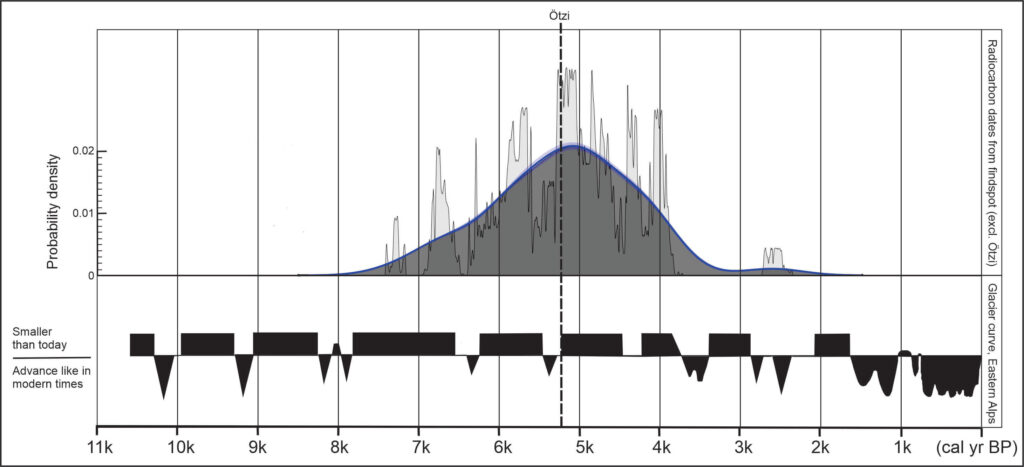

What does the evidence say? With a permanent burial of Ötzi and his equipment by ice like in a time capsule, the radiocarbon-dated material from the bottom of the gully should all derive from before or at his time of death, not later. A 2014 report by Walter Kutschera and colleagues summarizing the available radiocarbon dates shows that this is not the case. The material not related to Ötzi based on the radiocarbon dates is mostly of natural origin. The exception is a piece of cut green alder, radiocarbon-dated to 800-410 BC, i.e. the Hallstatt period.

The radiocarbon dates clearly show that material was repeatedly added to the assemblage in the gully. This could only have happened if the find spot was also repeatedly exposed. The gully started to collect material from c. 5300 BC and continued until c. 3800 BC. It is also worth noting that a piece of charcoal in the gully was dated to be about one thousand years older than Ötzi. Small pieces of worked stone from the Mesolithic were also found. Ötzi was not the first human at the site.

Most glacial ice in the Alps disappeared during the Holocene Thermal Maximum prior to Ötzi’s death. Then the ice started slowly to come back, a process known as the neo-glaciation, starting around a thousand years before Ötzi. Since then, glaciers in the Alps have varied in size. There is no clear evidence that the ice expanded suddenly at the time of Ötzi’s death, despite such claims in the scientific literature. Rather, this was a time of ‘small ice’.

The climate gradually cooled throughout the Holocene. It makes sense that the find spot would eventually be covered by so much ice that it was completely sealed off, even when ice retreat happened. According to the radiocarbon dates, this appears to have happened around 1500 years after Ötzi’s death. In the meantime, material accumulated in the gully. This shows that the gully and its contents must have been exposed by melting.

However, with repeated exposure of Ötzi’s body and the associated artefacts, why are they still remarkably well preserved? Recent results from glacial archaeology indicate that material from the ice does not break down as fast as previously believed. We are beginning to understand that the combination of the cold, high altitude environment and the only short and intermittent exposure does not lead to a rapid destruction of the material. It deteriorates, but it is not as if it is exposed one year and gone the next. As mentioned above, wood naturally freeze-dries when exposed on ice sites and can be preserved for many years while being intermittently exposed.

If we look at Ötzi himself, the publication clearly says that the fur cape was much better preserved beneath the body, as were his footwear. In fact, the fur cape had fallen into pieces above his back, leading to his naked back being exposed when he melted out in 1991. The skin on the back of his head had also flaked off, exposing the cranial bone there. Tellingly, this is the highest point of the mummy – the area most likely to have been repeatedly exposed. There is reason to believe that the upper part of his body was exposed on a number of occasions prior to the 1991 discovery.

Ötzi was not buried in the ice for 5300 years like in a time capsule. After being encased in the ice in the gully, he was intermittently exposed during melting incidents. This led to some damage to his body and the artefacts. The intermittent exposure of the gully led to the introduction of younger material to the finds assemblage, in addition to material already present here before Ötzi died. This tells us that scientists have to be careful in assigning undated material in the gully to Ötzi. Remember the sloe fruit?

The amount of ice on the find spot has varied in recent years based on aerial photos. There is no gradual retreat of the ice, although the trend towards less ice is clear. Some years show extensive snow coverage, some show bare ground and exposed ice only in limited areas. In Ötzi’s time there would have been a similar trend, albeit in the opposite direction, towards more ice over time. However, the snow coverage would have varied from year to year then as well. An immediate and permanent burial of Ötzi and his artefacts is unlikely.

Other Pass Sites in the Area

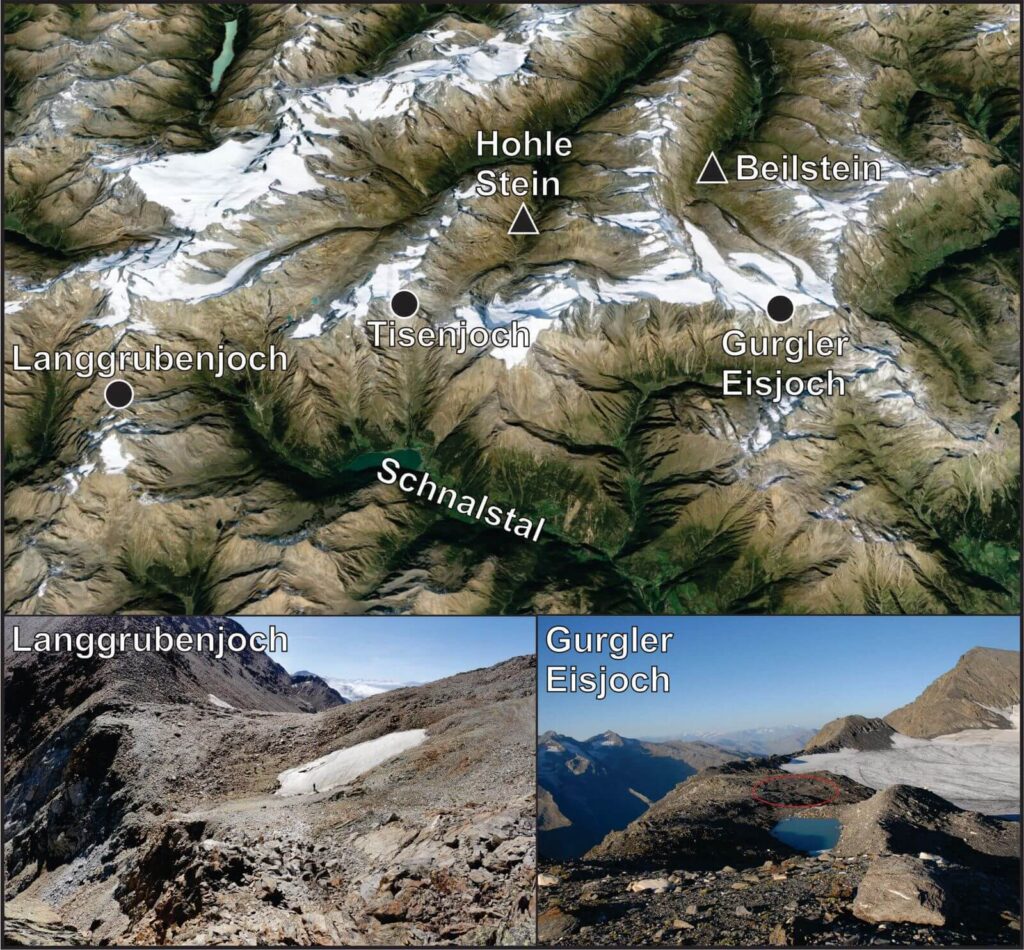

When Ötzi was discovered, there were few other archaeological remains from glaciated mountain passes. This also made Ötzi stand out in the archaeological record. This situation has changed. The finds from the Tisenjoch now fit into a pattern with other glacial archaeological pass sites in the Alps. Several discoveries have been made at nearby mountain passes during the last 10 to 20 years. As in the case of Ötzi, the discoveries were accidental and only afterwards closely examined and monitored by professional archaeologists. My colleague, Swiss glacial archaeologist Thomas Reitmaier, took a closer look at these discoveries.

The Gurgler Eisjoch (3134 metres), a connection between the Schnalstal/Pfossental and Gurglertal, is an important pass site. Here, a snowshoe from around 5800 years BP (Before Present, i.e. before 1950), wooden objects, arrow shafts and leather finds from 6500-5800 years BP as well as Iron Age and medieval artefacts were found in the vicinity of an ice patch. From the Langgrubenjoch (3017 metres) – a remote passage between the Matschertal and the Schnalstal valleys – a belt hook, pieces of clothing and even human remains from around 4500/4300 years BP were recovered together with large timbers from the Middle to Late Bronze Age, which were used there as roof shingles for a shelter.

The find situation seems very similar to the Ötzi site. A stationary ‘cold ice’ field at the highest point preserved the finds above a mobile warm-based temperate glacier. Typical damage to the wooden objects, like those on Ötzi’s equipment, are described for the Langgrubenjoch.

It is now clear that Ötzi is part of a greater story, which shows an intensive use of the high alpine landscapes. This activity has left traces both in the valleys leading to the mountain passes and in the passes themselves. Ötzi triggered a new and ground-breaking period in alpine archaeology, even though the Tisenjoch pass where he was found has itself remained relatively little investigated by archaeologists.

The New Understanding of Ötzi

About 5300 years ago, Ötzi died in a high mountain pass in the Alps. According to the original explanation by Spindler, Ötzi fled to the mountains with broken equipment, died in a snow-free gully and was quickly covered by snow and ice. The ice in the protected gully preserved him like in a time capsule, sealed beneath a moving glacier. He was saved by a miracle. This is the official Ötzi story, still told by the Ötzi Museum in Bolzano today. Based on our re-examination of the evidence, and our own field experience from glacial archaeology, we have presented a different explanation. We think it fits the evidence better and does not need a string of lucky coincidences to account for the preservation.

Based on the available evidence, Ötzi died in late spring or early summer, and lay on the snow where he died for a period. This allowed the body to freeze-dry, saving it for posterity. After some time, the snow and ice containing the body melted. Ötzi and most of his belongings slipped into a gully beneath, where the discovery was later made. This re-positioning of the find may have happened during one heavy melting situation, or during a series of smaller melting events. The missing parts of the equipment did not make it into the gully and were eventually lost. Snow and ice re-covered the gully. A field of non-moving ice covered Ötzi, not a basally sliding glacier. Some of the equipment broke and was displaced due to natural processes on the site.

During very warm summers, the ice-cold grave of Ötzi would occasionally re-open, as the ice cover was not very thick. This led to the deterioration of the most exposed parts of the body and the artefacts. At the same time, it allowed more recent material to enter the gully. About 3800 years ago, the climatic conditions for ice expansion became so favourable in the Alps that ice and snow finally sealed it off from its surroundings. There was never a moving glacier at the find spot, only ‘cold ice’ frozen to the ground. At the end of the 20th century the ice again melted back to a degree that it re-exposed the body and the artefacts.

Looking at the Ötzi find this way, it is no longer an anomaly in the world of glacial archaeology, quite the contrary. Ötzi died on the snow, which is how most ice finds are originally lost. Together with the artefacts, he eventually melted down into a gully, a typical way topographical features will trap ice artefacts. A non-moving field of ‘cold’ ice preserved the mummy and the artefacts, just like the other old finds from the ice. The find spot itself was not sealed off like a time capsule. More recent material is mixed with earlier finds as on other ice sites.

This new story is obviously not the appealing and clear narrative provided by Spindler’s original Ötzi story, which combined a series of serendipitous circumstances to preserve a unique moment of the past. Maybe this is why the original story is still told, even after new scientific evidence proved that it was unlikely. However, the litmus test is this: If Ötzi had been found now, with all that we have learned about glacial archaeology in the last decades, would glacial archaeologists have suggested Spindler’s explanation for the preservation of the find? The short answer to that is no.

Ötzi is still a fantastic find, but the find circumstances are not so special as claimed. In fact, they are quite normal for glacial archaeology. This is actually very good news. It means that the chances of finding another ice mummy are higher than previously believed, since a string of special circumstances are not needed for the preservation of this type of find. There may be more Ötzis out there waiting to be discovered!

The melting of glaciated mountain passes is ongoing. Let us see what happens.

You can read and download our open access paper on Ötzi here.

Press-release and photos with captions/credits available here