After two winters of heavy snow in 2004 and 2005, the summer of 2006 was exceptionally warm. By September, the accumulated snow from the previous years had melted, and the ice melt started to go deep. The melting continued until early October, longer than in typical years when it usually halts in September.

If you came straight here, you may want to read this post about the pre-2006 ice finds first)

First Finds from Langfonne Ice Patch

Reidar Marstein, our local helper from Lom, began finding scaring sticks at Storfonne ice patch in late August. He had also discovered scaring sticks there in 2002 and 2003.

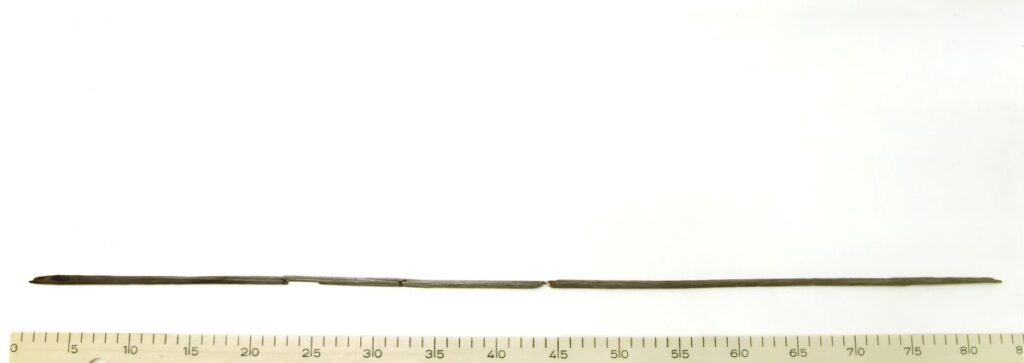

In early September, Reidar discovered the first artefacts at the neighbouring Langfonne ice patch – two arrows. Remarkably, one of these artefacts pre-dated the Iron Age — an arrow shaft made from a shoot of Fly Honeysuckle, with sinew still preserved around the front. We only discovered that it dated to 1600 BC (Early Bronze Age) when we radiocarbon-dated all the Langfonne arrows ten years later. The other arrow Reidar found had an iron arrowhead, dating it to the Late Iron Age (AD 600-1050).

Reidar continued to monitor the melt at Langfonne during weekly visits.

When Reidar Found the Shoe at Langfonne

Reidar explains what happened next:

It was my visit on September 17 that became the greatest adventure. I started early in the morning and reached the Langfonne ice patch around 9 am. It was unbelievable how much the ice patch had melted just during the last week. With great excitement, I started my survey around the ice. It had to have been a long time since the last human had set foot here.

After a while, a hunting blind appeared. About 25 metres above the hunting blind, I noticed something lying on the ground. I got my camera and GPS ready, as I had to note the location of the find and take a picture of it. After lifting the object with great care and gently removing some glacial silt, I realised that I was holding a shoe in my hand. Not a regular shoe, but a shoe that had to be incredibly old. I felt confident that it was a reindeer hunter with bow-and-arrow, who had once used it. It was a strange feeling standing at the edge of the ice holding the ancient shoe …

It was clear to me that I was holding a treasure from the past in my hand. The shoe had to be treated with great care. I wrapped it in plastic and paper and put it into a plastic box.

Back home, I put the shoe in the freezer. The next day, I called county archaeologist Espen Finstad, who visited me and collected the find.”

The Early Date of the Shoe is revealed

In the spring of 2007, we radiocarbon-dated the hide shoe to be 3,300 years old, from the Early Bronze Age This early date came as a complete surprise. It was much older than other dated finds from our mountain ice. They had generally not been more than around 2,000 years old. Only later, after systematic surveys at Langfonne and the recovery and radiocarbon-dating of many more artefacts, did it become clear how the shoe fit into a broader chronological pattern at the site (read more here).

The discovery of the 3,300-year-old shoe marked the beginning of glacial archaeology in Innlandet County. The same autumn, many other finds emerged from the melting ice, but the shoe remained the most remarkable. More than anything else, it made us realise that something both exciting and disturbing was happening in our high mountains.

The shoe was published in a scientific paper (in Norwegian) in 2008.

The September 28 2006 Triple Survey

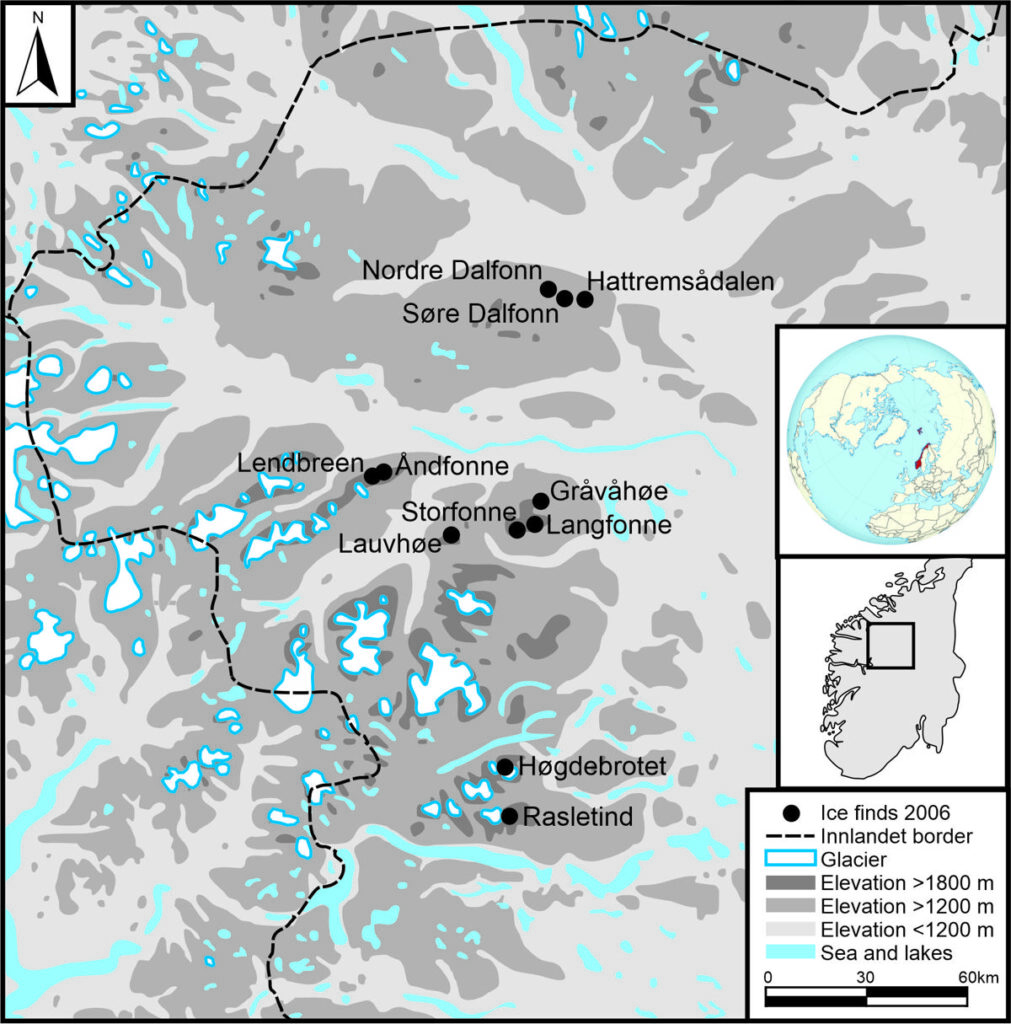

Storfonne and Langfonne were not the only sites yielding finds in September 2006. Reports indicated that artefacts had also melted out from other known sites, such as Lendbreen, Åndfonne, and Søre Dalfonn. Additionally, mountain hikers discovered arrows at previously unknown sites in the Jotunheimen mountains. We urgently needed to take action.

Archaeologists from the county council and the archaeological museum in Oslo teamed up with local helpers. On September 28, three separate survey teams were dispatched to Langfonne, Søre Dalfonn and Lendbreen/Åndfonne. The date is significant, as it marks the beginning of systematic archaeological fieldwork at the ice — work that continues to this day. Instead of relying only on reports from mountain hikers, we set out on a mission to locate and investigate the archaeological ice sites in a more organised manner.

At the time, we had no idea of the scale of the challenge ahead. In hindsight, this was probably fortunate. Thankfully, we continued to receive valuable help from the local community.

Langfonne Ice Patch

Eleven days after Reidar discovered the shoe, the survey team arrived at Langfonne ice patch. Reidar, along with his friend Jan Stokstad, also joined the team. What followed was an extraordinary series of discoveries: nine arrows, two arrowheads, a flag for a scaring stick and two pieces of post-medieval textile. We had never seen anything like it and would not witness such an amount of arrow finds from a single site again until the Secrets of the Ice team returned to Langfonne for a large systematic survey in 2014.

Later radiocarbon dates of the finds from the 2006 Langfonne survey revealed that Stone Age artefacts had begun to emerge that year. We dated one of the arrows to the Late Neolithic, around 4,000 years ago. Three arrows were from the Bronze Age, two from the Early Iron Age and three from the Late Iron Age and Early Medieval Period.

Søre Dalfonn Ice Patch

Mountain hikers reported the first finds from the Søre Dalfonn ice patch in 1947-48, and again in 1980 and 2002.

Starting in late August 2006, hikers reported finds from Søre Dalfonn and the neighbouring Nordre Dalfonn. Most finds came from Søre Dalfonn: three arrows, one arrowhead, parts of shoes, a horseshoe, scaring sticks and other artefacts. Generally, the finds appeared to date from the Iron Age and the Medieval Period.

The visit by archaeologists and local helpers to Søre Dalfonn on September 28 did not result in additional discoveries. This was likely because Søre Dalfonn is quite small, and many local mountain hikers had already visited the site in the preceding weeks, collecting the finds and handing them in to the local museum. By the time of the archaeological survey, the Søre Dalfonn ice patch had been emptied of melted-out artefacts.

Lendbreen and Åndfonne Ice Patches

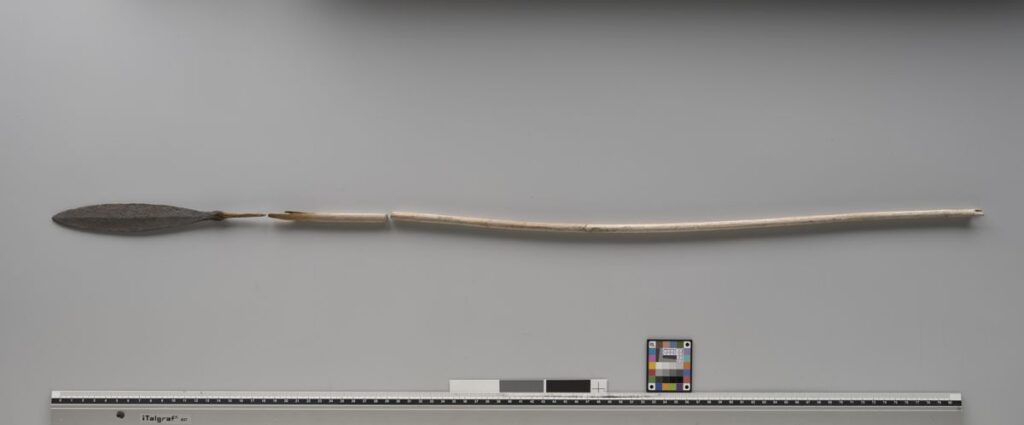

In 1973 and 1974, mountain hikers reported the earliest finds from Lendbreen, including an exceptionally well-preserved Viking Age spear that Per Dagsgard discovered. Around 1980, Dagsgard made the first finds at Åndfonne, a collection of scaring stick flags. In 2006, before the September 28th survey, local mountain hikers reported new finds from both Lendbreen and Åndfonne. They recovered and reported an iron scythe and three scaring sticks from Lendbreen, while they reported scaring sticks from Åndfonne.

The September 28th survey team, which included Per Dagsgard, focused on Lendbreen first. They discovered several artefacts there, including a horseshoe and an arrow. Another find was a small, hook-shaped wooden object, which was a mystery at the time. We now know it is linked to the traffic of packhorses passing through the area. The actual pass at the top of the ice patch only melted out five years later, so we had no knowledge of the pass in 2006.

The team then moved on to Åndfonne, where they immediately noticed large numbers of scaring sticks. They collected one as a sample, and this was later radiocarbon-dated to be around 1,500 years old.

The three teams meet

After the three survey teams had completed their work on September 28, they gathered the same evening in Otta, a small town at the junction of the Gudbrandsdalen and Ottadalen valleys. From the discussions that night, it became clear that something remarkable and puzzling was happening in the high mountains. Finds were emerging from the ice in numerous places. Why were so many artefacts melting out?

Storfonne Ice Patch

Let us explore some of the other ice patches where finds appeared in 2006. We start by returning to Storfonne. In addition to the scaring sticks found by Reidar, he also found the mid-section of an arrowshaft at Storfonne that year. Two other mountain hikers found and reported one arrow each here in 2006. One of these arrows was broken in six pieces. It was later dated to the earliest Iron Age, 2,200-2,300 years old. The other arrow was complete and had a preserved arrowhead which placed it in the Early Medieval Period. This was later confirmed through a radiocarbon-date of the wooden arrow shaft.

Gråvåhøe Canyon Ice Patch

A third ice site appeared at Kvitingskjølen, the mountain range where both Storfonne and Langfonne lie. This site is located in a canyon at 1,600 metres, below the Gråvåhøe mountain. A local mountain hiker found a wooden spade here. We radiocarbon-dated to around AD 300-500.

In the years to come, we discovered more ice sites in the Kvitingskjølen mountain range. The Handklefonne ice patch, close to Langfonne and Storfonne, yielded numerous finds in 2011 and the following years, while Reidar discovered a single arrow from a small ice patch further north in the range in 2023.

Lauvhøe Ice Patch

Aud Marstein, Reidar’s wife, found the first artefact from an ice patch below Mount Lauvhøe, west of Kvitingskjølen, during the big melt in 2006. This was a bolt for a crossbow, found in front of the lower edge of the ice patch. It is probably around 500 years old.

There would be a few more finds from the ice patch at Lauvhøe in the years to come. We surveyed the site systematically in 2017.

Nordre Dalfonn Ice Patch

In mid-September, local mountain hikers reported three finds from Nordre Dalfonn ice patch, two km northwest of Søre Dalfonn ice patch. The most remarkable find was a piece of textile, which the textile expert at the archaeological museum estimated to be medieval of origin. This was the first find of textile from an ice patch in Innlandet. There would be many more to come. The other two finds from Nordre Dalfonn were remains of scaring sticks.

Hattremsådalen Snow Patch

A mountain hiker reported finds from a small snow patch at Hattremsådalen, 2 km east of Søre Dalfonn. The snow patch sits in a cul-de-sac at the southern end of a canyon at 1,340 meters, making it the lowest glacial archaeological site in Innlandet County by far. The Hattremsådalen patch does not have an ice core, hence the use of the term snow patch for this site.

The hiker collected finds at Hattremsådalen on two occasions in October 2006. When he discovered the site, he brought down an iron arrowhead, four scaring sticks, and five flags. Later in October, he removed an additional fourteen scaring sticks and a thicker stick from the site and handed them in to the archaeologists..

Photos of the site, taken on October 4, 2006, show that the snow patch had nearly melted away, with only a little snow left at the bottom of the gully. There is clearly no ice core present in 2006, only snow.

We returned to the site in 2011 and collected even more finds.

Two Iron Age Arrows from the Southern Jotunheimen Mountains

Mountain hikers found two Early Iron Age arrows near melting ice in the southern Jotunheimen mountains in 2006, an area with no prior ice finds. The arrows both have the same type of iron arrowhead with a flat tang, which places them in the period AD 300-600.

2006: A Watershed Year for Glacial Archaeology in Innlandet

As we have seen, the autumn of 2006 not only led to new discoveries from four known ice sites (Lendbreen, Åndfonne, Storfonne and Søre Dalfonn), but mountain hikers also made finds on seven new ice patches, some close to known ice patch sites and some in new areas. We started to realise that the melt-out was not a freak of nature event but linked to climate change, and that we were standing at the start gate of a race to rescue the invaluable artefacts.

It became clear to us that we were facing several great challenges. We needed to gain an overview of where the sites were, how many sites there were and how to recover the finds from them. It was a daunting task. We had no funding and no idea of the magnitude of the problem. The road ahead looked tough and unpredictable.