The winter of 2015/16 brought heavy snowfall to the western mountains of Innlandet, while the eastern and northern ranges saw less than usual. Yet, with the lingering snow from 2015, the 2016 melt still was not enough to expose the old, dark ice in those areas.

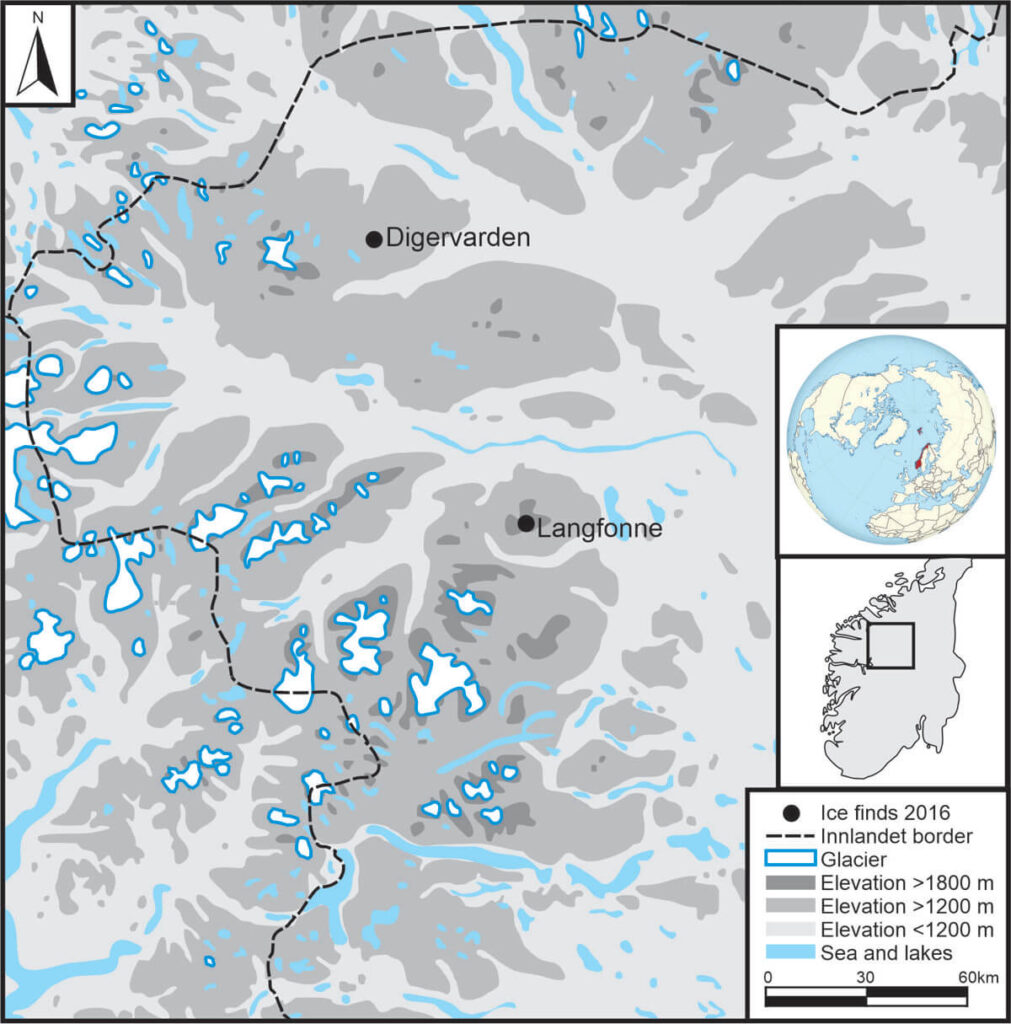

Even so, we accomplished a great deal in the field. We carried out the first systematic survey of the Digervarden ice patch, where we had discovered a pre-Viking ski just two years earlier. We also returned to the arrow-rich Langfonne site, and right at the very end of the season, Reidar Marstein made a remarkable discovery. And not least: The Secrets of the Ice website and social media was launched.

Digervarden Ice Patch

We had been eyeing the ice patch at Mount Digervarden for years. In 2014, we finally managed a first exploratory survey — and hit the jackpot with a 1,300-year-old ski. It was one of the most exciting finds in our programme so far, but it raised a tantalising question: where was the other ski of the pair?

In 2016, we returned with a bigger plan. This time, we brought a full team and the help of a packhorse to carry food and gear. The climb to our basecamp took three hours, with heavy loads and high expectations.

Our hope was simple: find the missing ski. But nature had other ideas. A thick layer of snow from the previous winter still covered much of the ice, keeping any hidden treasures firmly out of reach. Instead, we turned our attention to the newly exposed, lichen-free ground spread out around the ice.

The site is vast. The extent of the lichen-free ground and the ice is 1.35 million square metres. There is a string of smaller patches of ice along a north-east-facing slope. We knew from 2014 that Digervarden was not rich in artefacts, so we chose to focus on a coarse mapping of the site. Surveyors spread out in a long line, ten metres apart, scanning the ground for artefacts and bones. It was clear that most of the finds and bones clustered around the largest ice patch — the very place where the Iron Age ski had turned up two years earlier.

Then came our top Digervarden find of the season: the broken remains of a small sled. Scattered across the ground but largely complete, the sled had once been pulled by a skier. Later radiocarbon dating placed it in the 18th century — a rare glimpse into the icy world of the Little Ice Age (AD 1450–1850).

Back in 2016, we left disappointed about the missing ski. Little did we know we would return five years later to complete the pair — the best-preserved pair of prehistoric skis ever found.

Langfonne Ice Patch

In late August, we returned to Langfonne, the site of our incredible arrow discoveries in 2014. This time we made a dramatic arrival — a helicopter lifted the team and equipment straight onto the site. It was the last time we would use helicopter transport. From 2018 onwards, we turned to packhorses and human carriers to reduce the carbon footprint of our work.

When we last surveyed Langfonne in 2014, the once-mighty ice patch had already split into three. But the heavy snowfall of 2015 had stitched it back together into one large patch. That didn’t bother us. We had already combed the edges of the ancient, dark ice two years earlier. Now our task was to search the lichen-free ground further out.

Because we were working further from the ice, the finds were fewer and less well preserved than in 2014. But Langfonne still delivered: twelve more arrows emerged from the melting ice. Not quite the bonanza of 2014, but enough to remind us that this had been a favoured hunting ground for thousands of years.

Our plan was to stay for eight to ten days and cover most of the remaining open ground. But the mountains had other plans. On the sixth day, the forecast warned of a thunderstorm. High on an exposed ice patch, lightning is no joke. We had no choice but to abandon camp. With the clouds rolling in, we grabbed what we could and made a hurried descent to the lowlands, leaving tents and gear behind on the mountain. Only after the storm passed could three of our team climb back up and retrieve the rest.

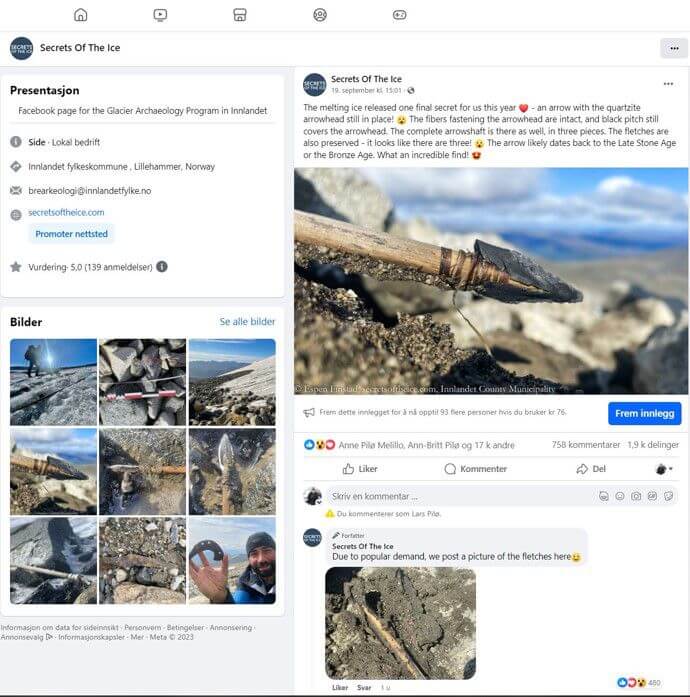

The storm cut our season short, but Langfonne still had one more secret in store. In late September, our longtime friend and helper, Reidar Marstein from Lom, visited the ice patch on his own and made an extraordinary discovery: part of an arrow shaft lying at the very edge of the ice. Radiocarbon dating showed it to be 6,100 years old — 800 years older than Ötzi, the Tyrolean ice man. This is the oldest object ever recovered from the Innlandet ice.

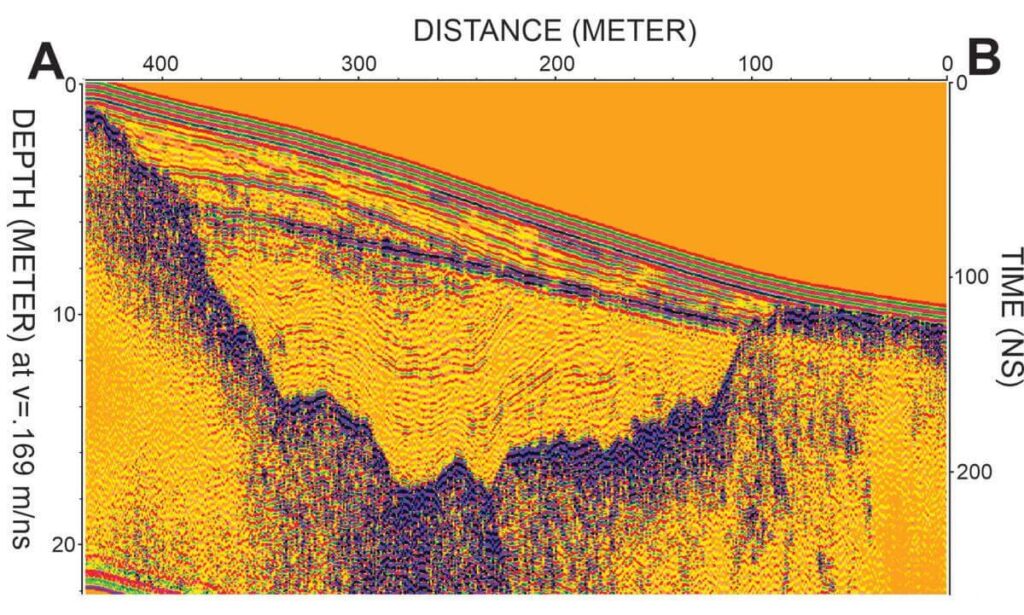

Work at Langfonne did not end with the close of the 2016 season. The following winter, a team of ice scientists carried out a ground-penetrating radar survey to measure the depth of the ice and study its internal layers.

The results were striking. The radar revealed that the ice was not standing still — it had been slowly creeping downhill, grinding and crushing whatever lay inside. That explained why so many arrows had been found broken: the ice itself was the culprit.

Science Norway reported from our fieldwork at Langfonne.

We published the Langfonne site in the journal The Holocene in 2020.

Since 2016, there has been little melt at Langfonne. We continue to monitor it closely, using both binoculars and satellite imagery. Once the melt resumes, we will be back.

The World Discovers Secrets of the Ice

The mountains weren’t the only place where things changed in 2016. That year, our work suddenly leapt onto the global stage. Word of our discoveries had spread far beyond Norway, and international media kept asking for interviews and background information. We found ourselves spending almost as much time explaining glacial archaeology as we did doing it. It was clear we needed a new way to share the story.

In August, we launched Secrets of the Ice online with a website and social media channels. For the first time, people could follow our fieldwork as it happened. We posted photos, videos, and discoveries straight from the mountains.

The response stunned us. Almost overnight, tens of thousands of people joined our community. Comment sections filled with curiosity: How old are the finds? Why is the ice melting? What does it mean for the future? We quickly realised that answering these questions was just as important as recovering the artefacts themselves.

The website became our anchor. It explains the nuts and bolts of glacial archaeology, and how our discoveries connect to climate change. That has proved invaluable — not only for engaging with the public, but also for helping journalists tackle a subject that is fascinating, but far from simple.

What began as a way to share information soon became a second adventure of its own, one that continues to grow, year after year.

Summing up 2016

Looking back, 2016 was a year of contrasts. The stubborn snowpack kept many secrets hidden, yet the ice still revealed a sled from the Little Ice Age, a dozen more arrows from Langfonne. Athunderstorm chased us from the mountains, but the season ended with the thrill of Reidar’s extraordinary find of an arrow shaft older than Ötzi. And while the fieldwork pushed our understanding further into the past, the launch of Secrets of the Ice carried us into a new future. Now our discoveries in the high mountains could be shared instantly with people all over the world.