After the 2006 big melt, we received limited funding to continue the work in 2007. We spent the money by doing exploratory surveys on two sites – Juvfonne and Lauvhøe ice patches. Elling Utvik Wammer and Lars Pilø conducted the fieldwork. Both were rookies in glacial archaeology, but both got hooked immediately, and became part of the program for many years (interview with Elling here).

Juvfonne Ice Patch

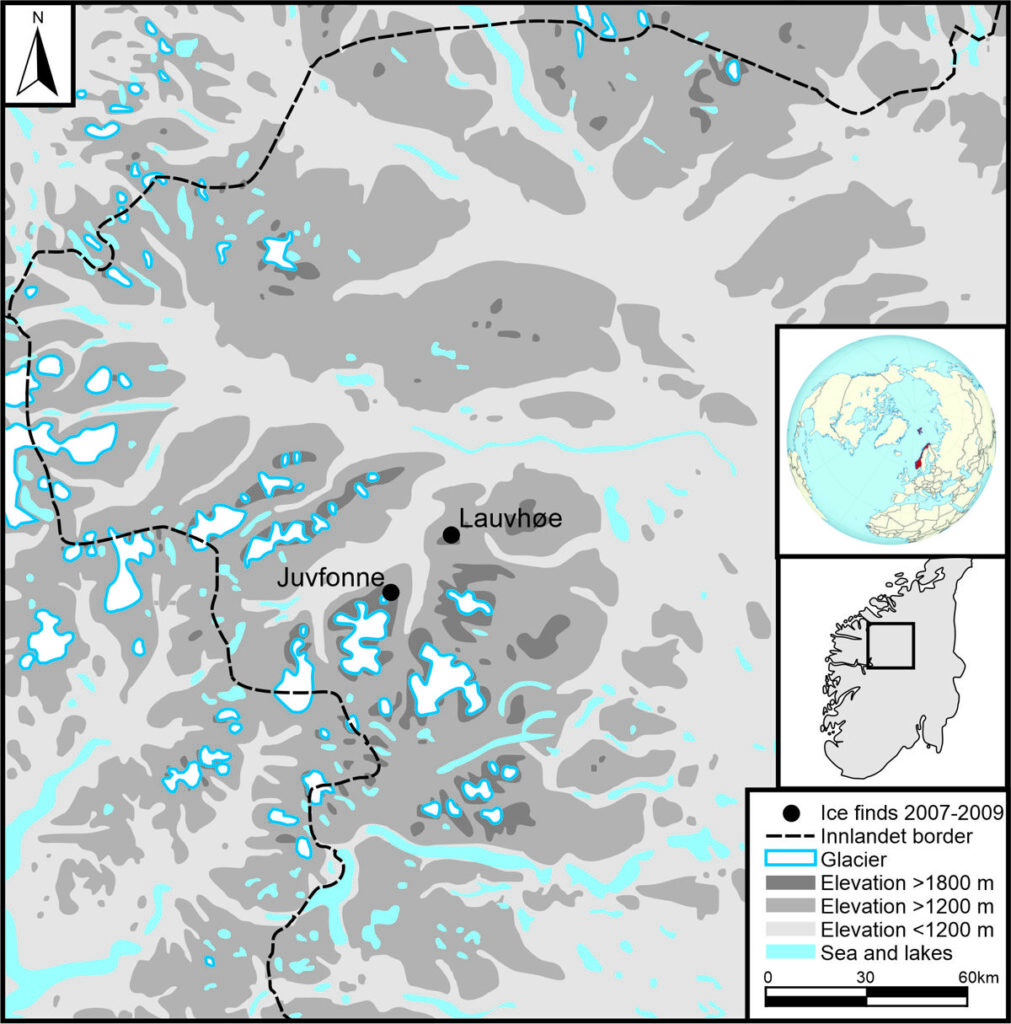

The Juvfonne ice patch (1850 m) is located on the Juvass plateau in the Jotunheimen mountains. In August 2007, local reindeer herder Jan Stokstad, who also participated in the 2006 survey at Langfonne, discovered numerous scaring sticks and stone-built hunting blinds at the site. We immediately prioritised this location, as we had been searching for an easily accessible site to gauge the number of potential finds it might contain and to estimate the work required for documentation and retrieval. Our goal was to develop a long-term, funded program for rescuing artefacts melting out of the ice, and we needed these numbers to inform the budget.

Juvfonne was an ideal test case from a practical perspective. As the only ice patch in our county, it is close to a paved road, providing easy access. The nearby Juvasshytta mountain cabin offered a place to eat, sleep, and shelter if needed.

Elling Utvik Wammer and Lars Pilø conducted the main fieldwork at Juvfonne in September 2007. They surveyed a 50-metre-wide sector perpendicular to the ice patch, recorded the positions of all scaring sticks within the survey area, and collected a selection for radiocarbon dating.

Over the winter of 2007–2008, we submitted twelve samples from the collected scaring sticks for radiocarbon dating. The results revealed that people used Juvfonne as a reindeer hunting site during the 5th and 6th centuries AD and again in the Viking Age, a few centuries later.

In addition to surveying the sector and sampling the objects, the team also measured the edge of the ice – a practice that would become routine in systematic surveys in the years to come.

In addition to the artefacts, the team also observed numerous stone-built hunting blinds at Juvfonne. Hunters used these structures as hideouts, concealing themselves until the reindeer came close enough to shoot with bow and arrow. The optimal shooting distance would have been as short as 10–20 metres.

During the fieldwork at Juvfonne, glaciologists visited the site and showed considerable interest in the artefacts recovered from the ice. A team from the national Norwegian broadcaster, NRK, filmed a news feature on-site, which aired on both regional and national TV news. The strong interest in what was, admittedly, a fairly small-scale survey at Juvfonne suggested early on that the ice finds held significant appeal for both scientists and the general public.

We returned to Juvfonne for a much larger survey in 2009 (see below).

Lauvhøe Ice Patch

In 2007, Reidar Marstein returned to the ice patch below Mount Lauvhøe, where a crossbow bolt was discovered in 2006. There, he found two arrows and several wooden sticks. In September 2007, Wammer and Marstein returned to the ice patch on a day hike to investigate and collect the finds. It became a very busy day.

They documented and collected the two arrows that Marstein had previously found and also discovered a third arrow. While examining the find spot of the third arrow, they had a surprise. Fragments of fletching appeared among the stones—the first such discovery in Innlandet. Unsure of the feathers’ fragility, they decided to leave them in place temporarily and covered the find spot.

A week later, Pilø and Marstein returned to retrieve the fletching. Pilø had consulted conservators at the archaeological museum for advice on handling the delicate find, which presented a unique challenge. Archaeologists typically find fragile artifacts buried in soil and stabilize them before lifting. In this case, the thousand-year-old feathers lay exposed on top of stones. After much discussion, we found a simple solution: we slid an iron spatula underneath the feathers and gently transferred them onto the spatula. We then placed the feathers into a finds bag along with a piece of cardboard to prevent bending. Finally, we carefully packed the bag containing the feathers into a box to protect it from pressure.

As it turned out, the three feathers were very well preserved and could have been handled more straightforwardly. However, as this was our first feather discovery, it seemed wise to err on the side of caution.

The Lauvhøe ice patch varies considerably in size depending on the amount of snowfall. Only the southernmost section contains a preserved ice core, and all the arrows were found in this area. The remainder of the ice patch has intermittent snow cover without permanent ice.

The three arrows found in 2007 date to AD 300–600, the Viking Age, and the mid-15th century, respectively. Late medieval arrows are very rare in Innlandet, making the Lauvhøe arrow an exceptional find. The scarcity of late medieval arrows is likely related to a low reindeer population at the time. Hunters nearly drove the reindeer to extinction during the Early and High Medieval periods (AD 1050–1350), when a market developed for reindeer pelts and antlers.

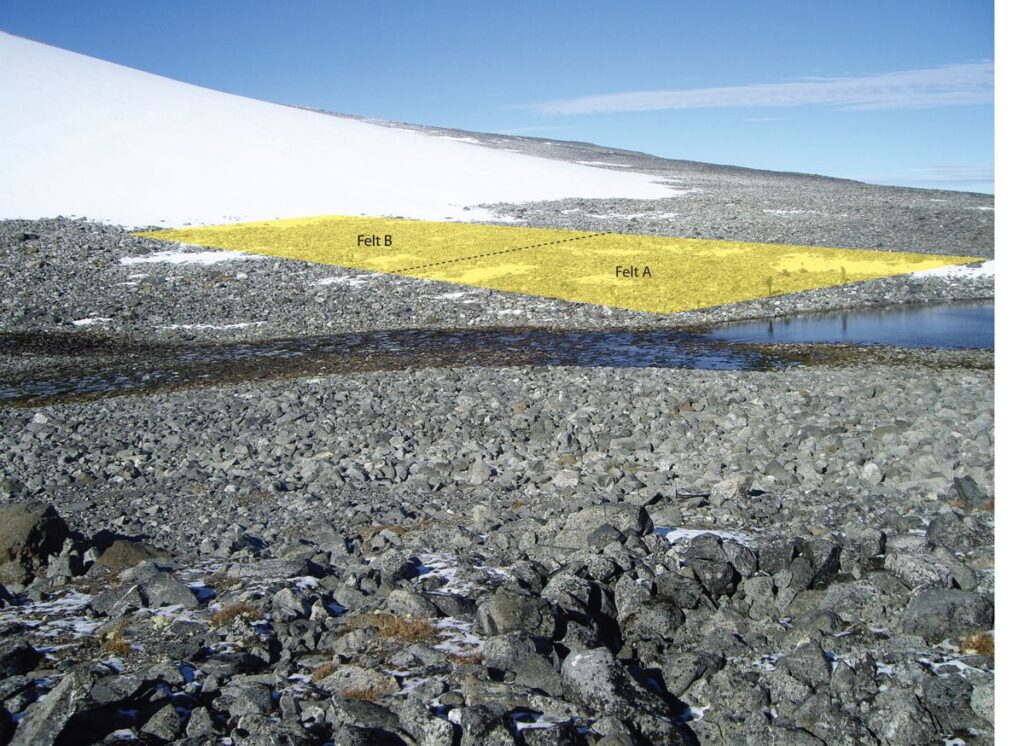

In the northern part, there was only intermittent snow cover present. Here was a large concentration of wooden sticks. Their preservation was poor due to the lack of permanent ice in this area. Wammer and Marstein collected four of these sticks, and we radiocarbon-dated one of them to the 11th and 12th centuries AD. These sticks are more robust than scaring sticks and are of a later date. Hunters likely built them as part of a solid fence to prevent reindeer from exiting the ice patch in that direction. They also connected them to other hunting installations on the plain below.

Reidar discovered a few more artefacts at Lauvhøe in 2011. We returned to Lauvhøe for a large systematic survey in 2017 and again for a brief monitoring visit in 2023.

2008 – too much snow and no funding

After the promising discoveries of 2006 and 2007, 2008 was a disappointing year. We had no funding, and heavy winter snow rendered it impractical to survey known sites. Consequently, we decided to suspend fieldwork.

In a way, this turned out to be a blessing—not only for the ice, which received a brief respite from melting that year. It allowed us to develop our plans for a larger programme to address the needs for rescue work. If you have worked with funding programmes, you will know that even when the necessity for a specific program seems self-evident to you, there are many initiatives competing for funding. Navigating the funding landscape and securing support—especially long-term funding—can be very challenging, regardless of how urgent and well-documented the needs may be.

Let me provide an example. Researchers discovered in the late 1980s that some mountainsides in the fjord landscape of Western Norway were unstable. Measurements indicated that cracks were developing in the cliffs. If they expanded, the mountainsides could eventually collapse into the fjords, generating deadly tsunamis. Don’t just take my word for it—this occurred twice in the early 20th century, resulting in significant loss of life and property. Lives could have been saved with an early warning system in the mountains that would alert residents if the cracks began to expand rapidly, allowing them time to evacuate. Surely, such a life-and-death program would have received immediate funding? No, it took more than a decade of meetings and lobbying before the first monitoring systems were installed.

This serves as a sobering piece of background for archaeologists trying to rescue well-preserved artefacts emerging from melting ice. For us, this is a noble and worthwhile cause, but we wondered if these finds were significant enough in the public eye to secure funding. It became clear that we needed to broaden the relevance of the finds beyond their archaeological significance. Climate change, the context of the finds, the reason they were melting out, needed to become an integral part of our work.

During the winter of 2008/2009, we began to develop ideas to transform the Juvfonne ice patch into an outdoor arena for public outreach on glacial archaeology and climate change—a climate park. Politicians often travel to the high Arctic to witness the effects of climate change, as these impacts are very visible there. However, the effects are equally apparent in the high mountains, particularly in Innlandet. Given its proximity to a paved road, Juvfonne seemed an excellent choice for such an outdoor outreach arena. Even better was that there was already on-going climate monitoring on the Juvass plateau near Juvfonne, including permafrost temperature measurements and an automatic weather station.

If Juvfonne were to be developed as a climate park with many visitors, we first needed to conduct a large systematic survey of the entire site to collect the numerous finds that had been exposed. We also needed to document all the hunting blinds and other ancient monuments. Fortunately, we were able to secure funding for this work through the county council.

2008 also saw the first international conference on glacial archaeology and climate change in Bern, Switzerland: “Ötzi, Schnidi and the Reindeer Hunters: Ice Patch Archeology and Holocene Climate Change.”, where we participated. “Frozen Pasts” was established in the aftermath of the conference – an international network of archaeologists, researchers, heritage managers, students and others interested in frozen archaeology and history.

2009 – Back to Juvfonne

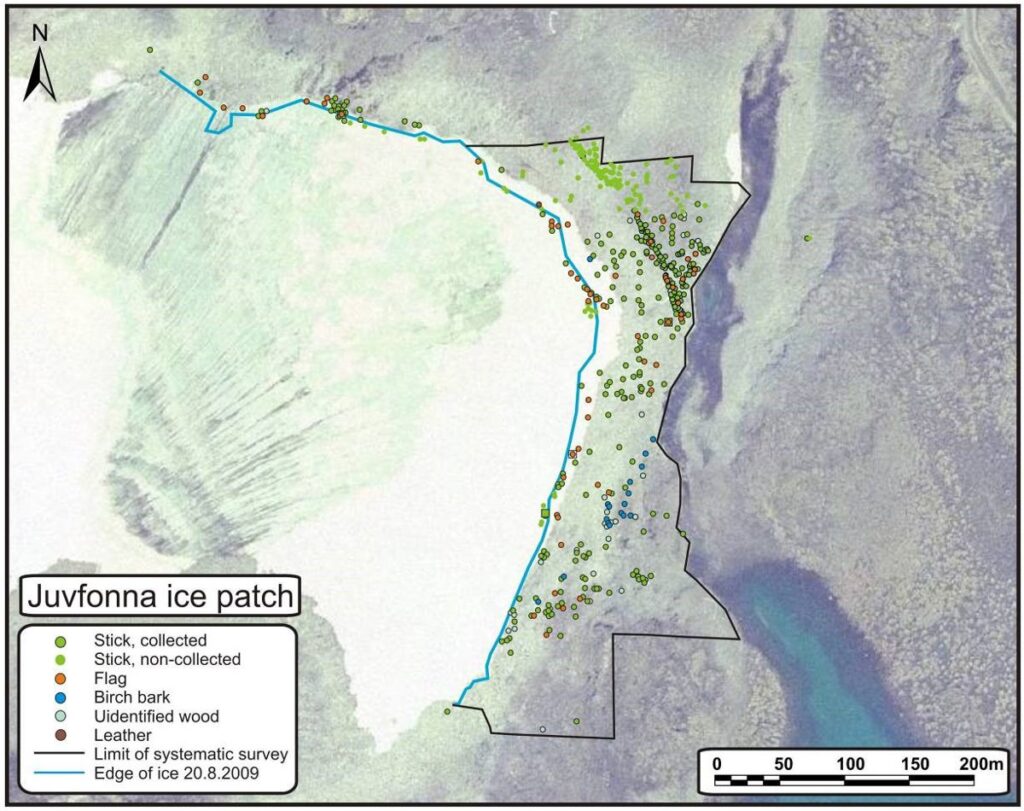

We returned to Juvfonne in early August 2009 for a large systematic survey, working on the site for 18 days. This was likely the first time the exposed ground surrounding an ice patch had been surveyed in such a systematic manner. Previous surveys of find-producing ice patches had focused primarily on recovering artefacts at the edge of the ice. The 2009 survey at Juvfonne demonstrated that there were also finds up to one hundred metres away from the ice’s edge.

We ended up covering an area of 50,000 m² with a dense survey, resulting in the recovery of 400 artefacts. This was an astounding number—more than had been recovered from the mountain ice across all of North America at the time.

Nearly all the finds were scaring sticks. The distribution of the finds indicated a clear line of scaring sticks in the northeast. This line would have formed a fence to block reindeer from accessing or exiting the ice patch from/to that direction.

We also mapped all the stone-built hunting blinds at Juvfonne. In total, we discovered 51 hunting blinds, most of which were located on the eastern side of the river. The line of scaring sticks blocking the entrance/exit would have directed the reindeer towards the hunters concealed in the blinds.

We invited two colleagues from the glacial archaeology community to join us at Juvfonne. Albert Hafner from Switzerland (whom we had met at the conference in Bern the year before), the investigator of the renowned Schnidejoch site participated. So did Martin Callanan from the University of Trondheim, who investigated the ice finds north of our county border, and was later to become the editor for the Journal of Glacial Archaeology.

This provided us with an opportunity to exchange views and experiences, which proved to be very useful. Hafner shared insights about his work in the mountain pass at Schnidejoch. He had encountered a vast array of finds on this site. We realised that mountain pass sites like Schnidejoch were quite different from the reindeer hunting sites we were familiar with in Innlandet. Inspired by this, we began to dream about discovering our own mountain pass site. Two years later, this was precisely what happened.

We were unable to survey the entire terrain surrounding the ice patch. As a result, we only measured the northern part of the scaring stick fence without collecting any finds from that area. This approach seemed reasonable, as leaving a section with artefacts behind would allow us to observe how they deteriorated over the years. Unfortunately, this plan did not work out as expected. A tourist discovered the scaring sticks, collected them, and then approached us to show “his” finds. It served as a reminder that leaving artefacts on sites can lead to problems, especially in areas with high foot traffic.

As mentioned, Juvfonne is located near a paved road and a mountain cabin. It was used for summer skiing in the 1970s before a large summer ski centre opened on a nearby glacier. Consequently, there were many modern finds on the site, which is usually not the case with our ice sites. We encountered modern textiles, slalom poles, iron nails, bullets, and building materials. In some parts of the site, it felt more like a modern rubbish removal operation than archaeological fieldwork. Given the excellent preservation of the Iron Age artefacts, it was sometimes confusing to distinguish between old and modern finds of wood.

One of the modern items we discovered was a wooden stretcher from a 1972 rescue operation. A skier at the summer ski centre broke a leg and needed to be transported down to the road. Winter road markers had been repurposed to create a makeshift stretcher. The stretcher was subsequently left behind, presumably because a proper stretcher had become available.

In addition to the archaeological fieldwork, significant outreach efforts were conducted at Juvfonne concurrently. Local schoolchildren visited the ice patch, and there was even a small climate camp for youth with international participation. These activities marked the first steps in establishing the Climate Park as an outdoor outreach arena. The Climate Park opened in 2010.

We returned to Juvfonne in late September 2009 to collect new finds that had emerged from the retreating ice. We made additional visits in 2010 following further ice retreat, as well as on several other occasions in the years to come. The site would also be monitored by the guides from the climate park. They alerted us to new finds when they melted out of the ice.

Finds From Langfonne and Åndfonne

In addition to the archaeological fieldwork at Juvfonne in 2009. finds from two known sites were also discovered and handed in to us – an arrow from Langfonne and scaring sticks from Åndfonne.

2007-2009: Summing up

In addition to the many artefacts, the systematic survey at Juvfonne provided us with valuable information on how to conduct a survey of a large glacial archaeological site. This would provide important background knowledge when we tackled new sites in the years to come. Juvfonne was an important first step in the development of our methodological toolbox.

It was heartening to experience the great public interest in our work. It made us determined to pursue public outreach as in integral part of our efforts in the years to come.

Lack of long-term funding was still a big problem. We needed to solve this as quickly as possible to be able to extend our fieldwork to new sites, now that Juvfonne was completely surveyed. The clock was ticking.