For years, we kept the identity of one of our ice sites hidden, referring to it as our “secret arrow site.” The reason for the secrecy was that it contained a treasure trove of arrows. In fact, it is the ice site in the world with the most arrows, and by a large margin. Doing fieldwork here and finding all the arrows was an incredible experience, an archaeologist’s dream. I remember telling the crew: “Enjoy the moment as much as you can. You will never experience anything like it again.”

We did not make the location public until the completion of fieldwork. That is now the case. All the arrows and other finds that melted out have been collected. Today we are publishing a major study of the site in the scientific journal The Holocene (free download).

The site is the Langfonne Ice Patch in the Jotunheimen Mountains, Norway. This was where Reidar Marstein found a shoe back in 2006. We thought that the shoe could perhaps be as old as the Viking Age if we were lucky. When the radiocarbon date came back it turned out to be much older – 3300 years old, from the Early Bronze Age. That find was a real shocker for us. It kickstarted the fieldwork at the ice in Innlandet County, which later developed into the Secrets of the Ice programme. However, the shoe was just the modest beginning of what Langfonne would reveal in the years ahead.

What is Happening to the Langfonne ice patch?

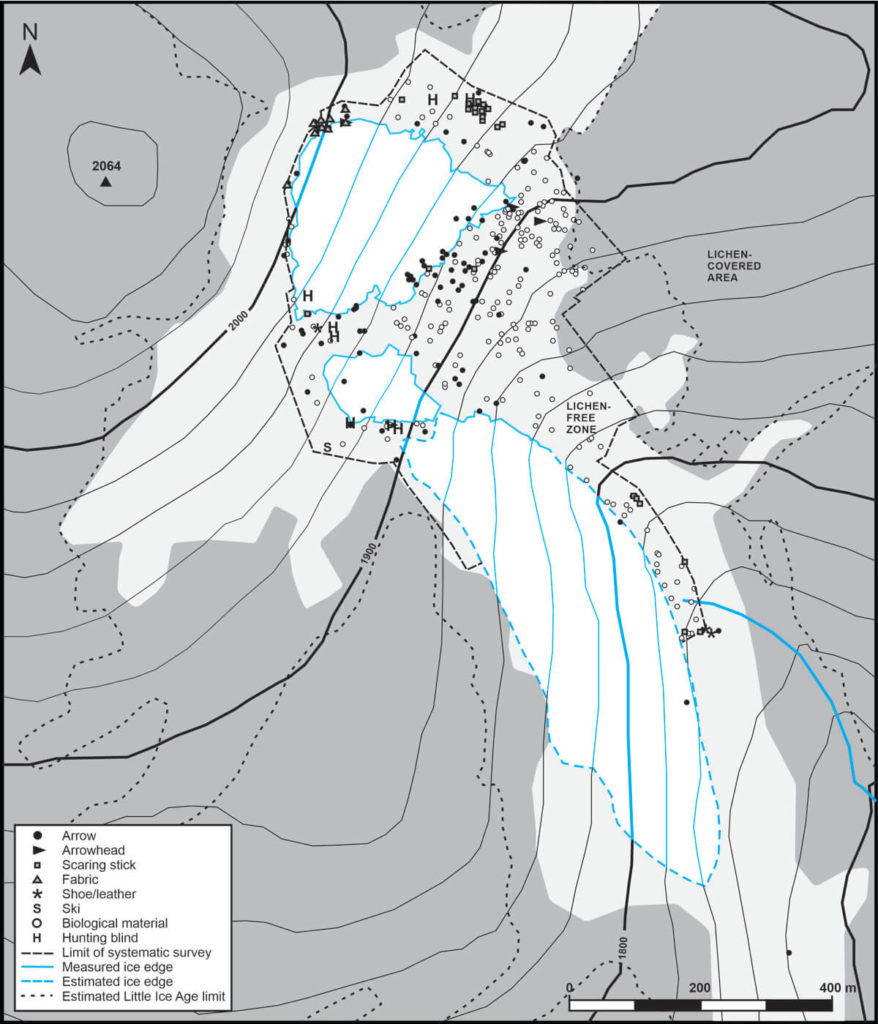

A few words on the Langfonne ice patch, before we dig into the finds. Langfonne has retreated dramatically in the last two decades. It is now less than 30% of the size it was twenty years ago. This retreat is clearly visible in the landscape. Light grey, newly exposed scree and bedrock without lichen and moss surround the ice. The ice has split into three different ice patches. Langfonne is now only 10% of the maximum extent of the ice during the Little Ice Age (AD 1450-1920). The melting of Langfonne is part of a much larger pattern of retreating mountain glaciers here in Norway and worldwide, linked to global warming.

The Finds From Langfonne

Langfonne was an ancient reindeer hunting site. We have recovered a record-breaking 68 arrows from the site, dating from the Stone Age to the Medieval Period. The earliest arrows are circa 6000 years old. This is earlier than finds from any other ice site in Northern Europe and about 800 years earlier than Ötzi.

The finds also include the Early Bronze Age shoe and the usual scaring sticks. In addition, we collected nearly 300 finds of faunal material, mostly bones and antlers from reindeer. With a few exceptions, the faunal material is of natural origin without signs of human interference. The age of this natural material provides an interesting contrast to the age of the artefacts.

The Mysterious Patterns

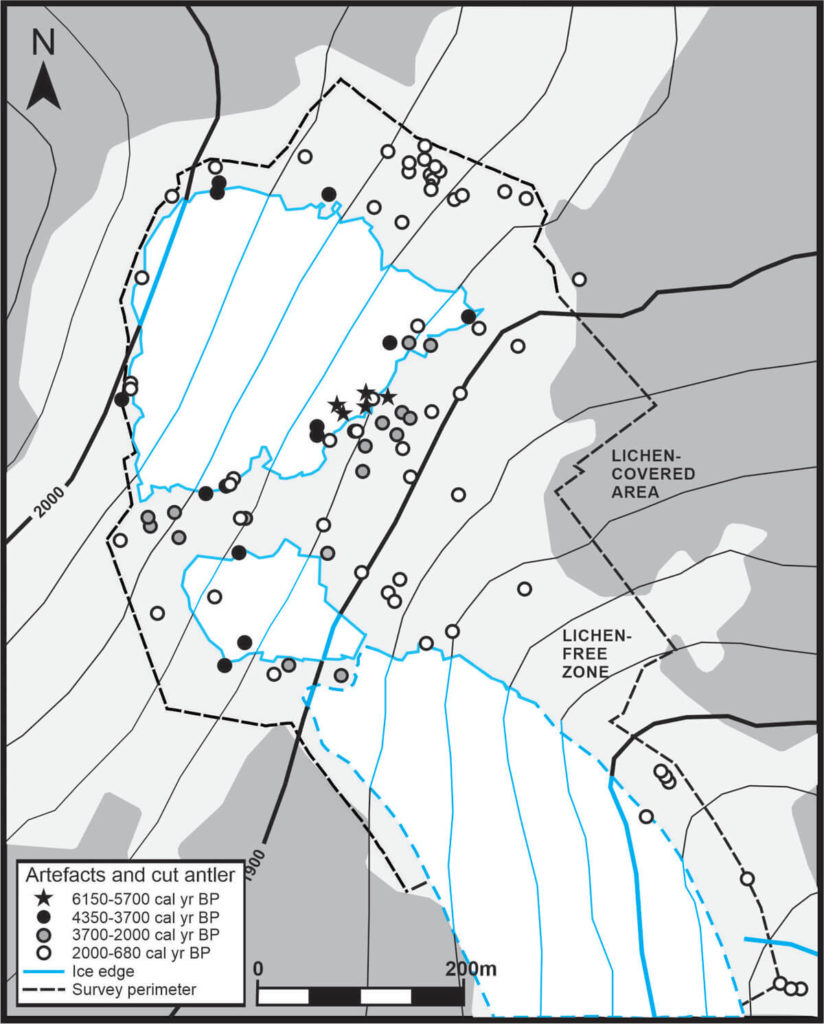

We have carefully recorded the position of each find in the field using a high-precision GPS. We have also radiocarbon dated 102 finds, including nearly all the arrows. This has resulted in a very detailed archaeological record and has revealed mysterious patterns at the site.

The record shows that there are patterns to where the artefacts lie on the site. We discovered many artefacts in front of the lower ice edge. The preservation of these finds is mostly poor, while finds along the sides of the ice and above the upper ice edge have better preservation. In addition, the Stone Age finds appear on the surface of the ice or very close to the present-day ice edge.

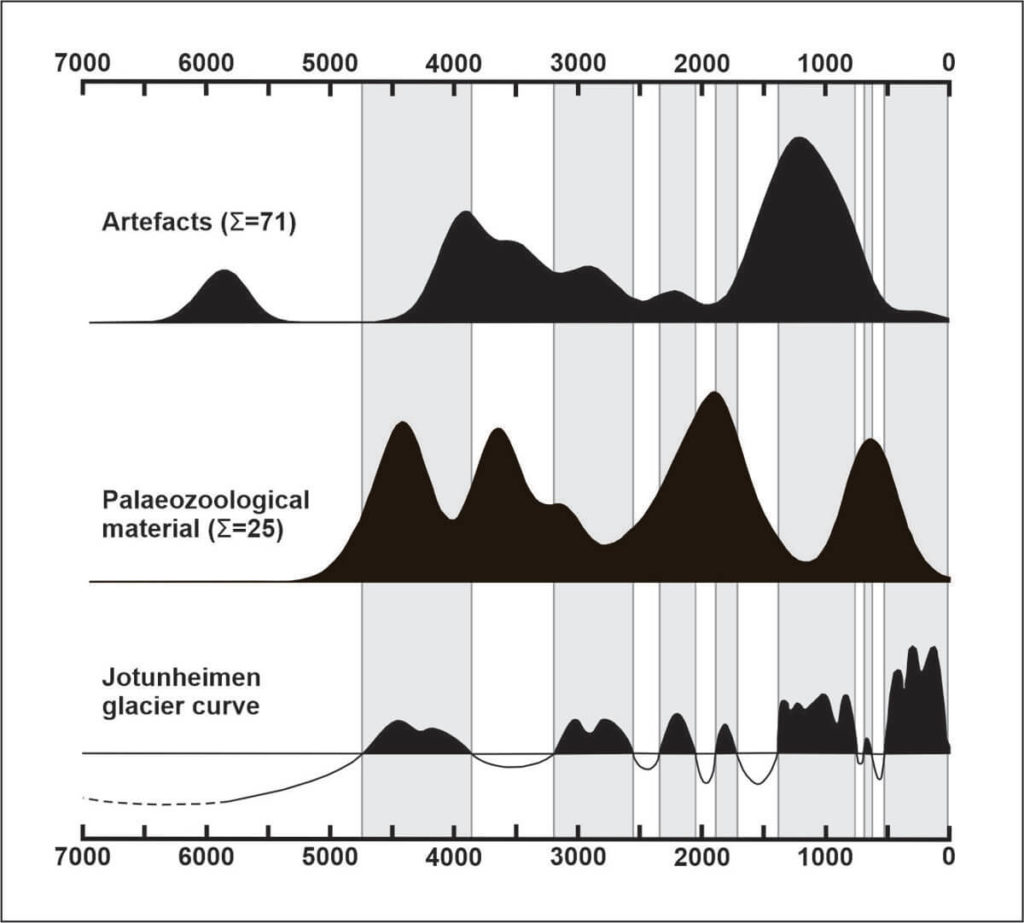

There is also chronological patterning, i.e. some periods have many finds while others have fewer. There are, relatively speaking, many arrows from the Late Neolithic (2400-1750 BC) and especially during the Late Iron Age (AD 550-1050). Other periods have few or no artefact finds. The number of dated reindeer bones also varies over time, but differently from the artefacts.

Preservation of the individual arrows is also variable over time. Not the way you would expect it with the arrows getting gradually better preserved the younger they are. Arrows from the Late Neolithic (2400-1750 BC) are well preserved and numerous, while arrows from the following 2000 years are poorly preserved and less numerous.

Humans vs Nature

The big question is whether changes in human activities at the site or natural processes caused these variabilities in artefacts and reindeer bones? It is important to keep in mind that ice patches are not your regular archaeological sites. They lie in the high mountains in a cold and hostile environment. The forces of nature are on a very different scale up here than at normal archaeological sites in the lowlands.

What happens to the finds once lost in the snow? How do ice movement, meltwater, heavy winds and exposure affect the finds? Is the impact of nature so massive that we cannot get historical information beyond what we can learn from the individual finds, say an arrow? This is a crucial, yet unsolved question in the new field of glacial archaeology. To put it very simply: Is the ice a preserver of finds but a destroyer of history?

The Crushed Arrows

Based on ice dates from the bottom of nearby Juvfonne ice patch, we believe that the ice in Langfonne formed around 5600 BC, but the finds do not go so far back in time yet. This may change as the ice patch continues to melt in the years ahead.

We have found six arrow shafts dated to around 4000 BC (the transition between the Mesolithic and the Neolithic). They are all very poorly preserved. This may appear like a natural consequence of their great age, but this is not so straightforward. We found two of the arrows on the surface of the ice just after they melted out. Arrows are quickly flushed downslope by meltwater once exposed, and end up on the ground in front of the ice. Finding the arrows on the ice surface thus implies that these arrows were probably not exposed previously. Normally when first-time exposure happens, artefacts are in a pristine condition. They look like they were lost yesterday. Instead, these arrow shafts showed poor preservation. This led to a suspicion that something had happened to them while inside the ice.

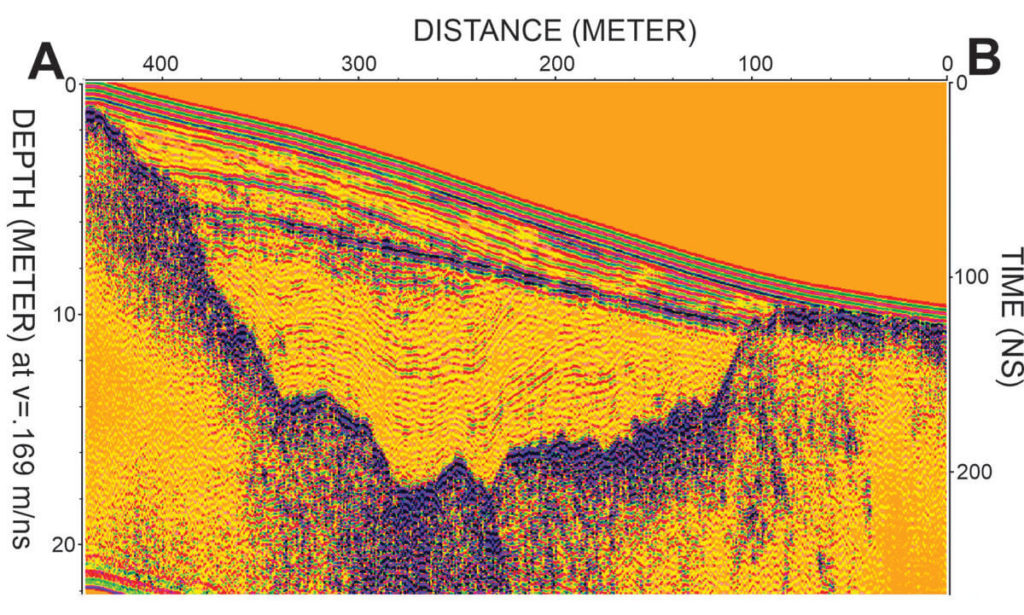

We believe that ice deformation deep inside the ice patch caused the poor condition of the earliest arrows. The ice literally crushed the arrows. But wait, aren’t ice patches supposed to be non-moving? Yes, ice scientists used to think that. New research, however, has shown that the ice inside large ice patches may slowly deform. We used a ground penetrating radar at Langfonne to check this. And sure enough: The radar revealed that the ice had been deforming and moving downhill, probably most markedly during the Little Ice Age (AD 1450-1920). This process also brought the very early arrows to the surface.

The Late Stone Age Arrow Finds Close to the Present-Day Ice

There is a hiatus in the finds after the cluster of early arrows. The arrows reappear in the Late Neolithic (2400-1750 BC). Most of these arrows are well preserved, even better than arrows thousands of years younger. The good preservation may be caused by the Late Neolithic being a time of glacier expansion in the Jotunheimen Mountains (where Langfonne is situated). It is common sense that finds lost in the snow are more likely to be better preserved during times of ice expansion, rather than during ice retreat.

Interestingly, all the Stone Age finds were recovered either on the ice or very close to the edge of the present-day ice. This may give us an indication that the ice was generally smaller during the Stone Age than it was later. However, we cannot be sure, as the ice could also have been a lot larger with arrows getting stranded far away from the ice during a later retreat, with a subsequent loss (we get to that below).

The Poorly Preserved Bronze Age Finds

The period from 1750 BC – AD 200 has a gradually reducing number of finds compared to the Late Neolithic. In addition, the arrows lie further away from the ice than in the Late Neolithic and are less well preserved. This period is a time of both glacier expansions and retreats, and the poorly preserved finds may reflect that. Due to the poor preservation, we should probably be careful not to try to read too much into the finds from this period.

The Iron Age Peak in Finds

From AD 200 onwards the number of dated arrows increases, peaking around AD 700-750, before the number decreases again. The most recent arrow dates to the early 13th century AD. Remarkably, only two reindeer antlers and no bones date to the period circa AD 540-1160. Both reindeer antlers have cut marks made by humans. The sharp rise of the number of arrows and the disappearance of reindeer bones at the same time is surely not a coincidence.

The finds from Langfonne tell us that reindeer hunting intensified just prior to the onset of the Viking Age. This is very interesting in a wider context. Recent analysis of combs in the 8th century AD emporium in Ribe, Denmark, has identified that some of them are made from reindeer antler. It supports recent ideas that long-distance trade in low cost commodities in Northern Europe started earlier than previously thought.

The reindeer hunt took place not only on the ice, but also off the ice using pitfall traps and mass trapping systems. The hunting pressure eventually became too much for the reindeer and their numbers dwindled. By the 13th century AD, the wild reindeer in the mountains of Innlandet County were nearly extinct.

The Iron Age and Medieval finds lie even further away from the ice than finds from previous periods. This may indicate that the ice was larger during parts of this period (but see below). This is in accordance with what we know about the size of the Jotunheimen glaciers at the time.

The Finds Distribution – Humans vs Nature

The analysis shows that ice movement, ice melt, meltwater and wind displaced most of the finds from the site. The clearest example of this is the concentration of arrows which we found on the foreland of the lower ice edge. A typical find here is part of an arrow shaft with no arrowhead and no remains of sinew or fletching. These arrows were exposed on the ice surface further up the slope and were damaged during meltwater transport downslope, until they ended up on the ground. Thus, the arrows in front of the ice do not indicate where hunting took place. Their presence here is a result of natural processes at the site. Originally, hunting took place more centrally on the ice patch.

Arrows found above the upper edge of the ice probably show more directly where hunting took place. These arrows are generally better preserved and half of them still preserve their arrowheads. There is also a line of scaring sticks northeast of the ice patch that appears to be in place. This would show where the Iron Age hunters blocked the exit from the ice patch for the reindeer.

There is a clear chronological pattern at Langfonne, with the earliest finds close to or on the ice, and the most recent finds further away from the ice. It is still an open question whether this means that the ice was generally smaller in the Stone Age than in the Viking Age. We may be seeing what archaeologists call a taphonomic overprint. This means that the artefacts will survive better over time, the closer they are to the ice, as this would limit their time length of exposure. At present, we think that both ice size and the decay of artefacts causes this chronological pattern over time.

Our conclusion

The case study at Langfonne shows that natural processes have seriously damaged the archaeological record at Langfonne. Even so, it is still possible to gather historical information beyond the individual finds, at least during some time periods. Taking the impact of nature into account, careful study of the artefacts and the biological material from ice patches can give us information of considerable value. At Langfonne, we learned that an apparent peak in the number of arrows around AD 700-750 is unlikely to be caused by natural processes. This shows the importance of glacial archaeology to our understanding of expanding resource extraction in Norway prior to the start of the Viking Age. It also provides a smoking gun for new ideas on early trade in Scandinavia.

Glacial archaeology is a new field in archaeology, still in its infancy. It has the potential to transform our understanding of human activity in the high mountains and beyond. However, in each case we have to carefully consider how natural processes may have altered the archaeological record. Without such analysis, we may mistake patterns in the record produced by natural processes for traces from human activities. The arrows upon arrows found in front of the receding ice do not point to an intensive hunt there. Gravity and meltwater sent the arrows downslope, and they ended up in front of the ice.

The Future of Langfonne

We have learned a lot about Langfonne’s past, but what about its future? With the current climate prognosis, most of the ice in the high mountains of Norway will melt away during this century. The future for the Langfonne ice patch looks bleak. With more melt in the pipeline, Langfonne has surely not given up all its secrets yet. We will continue to monitor the ice here in the years ahead.

National Geographic covered the Langfonne story here.